For more than a century, the United States Forest Service has employed men and women to monitor vast swaths of wilderness from isolated lookout towers. Armed with little more than a pair of binoculars and a map, these lookouts served as an early warning system for combating wildfires. Eventually the towers would be equipped with radios, and later still a cellular or satellite connection to the Internet, but beyond that the job of fire lookout has changed little since the 1900s.

Like the lighthouse keepers of old, there’s a certain romance surrounding the fire lookouts. Sitting alone in their tower, the majority of their time is spent looking at a horizon they’ve memorized over years or even decades, carefully watching for the slightest whiff of smoke. The isolation has been a prison for some, and a paradise for others. Author Jack Kerouac spent the summer of 1956 in a lookout tower on Desolation Peak in Washington state, an experience which he wrote about in several works including Desolation Angels.

Like the lighthouse keepers of old, there’s a certain romance surrounding the fire lookouts. Sitting alone in their tower, the majority of their time is spent looking at a horizon they’ve memorized over years or even decades, carefully watching for the slightest whiff of smoke. The isolation has been a prison for some, and a paradise for others. Author Jack Kerouac spent the summer of 1956 in a lookout tower on Desolation Peak in Washington state, an experience which he wrote about in several works including Desolation Angels.

But slowly, in a change completely imperceptible to the public, the era of the fire lookouts has been drawing to a close. As technology improves, the idea of perching a human on top of a tall tower for months on end seems increasingly archaic. Many are staunchly opposed to the idea of automation replacing human workers, but in the case of the fire lookouts, it’s difficult to argue against it. Computer vision offers an unwavering eye that can detect even the smallest column of smoke amongst acres of woodland, while drones equipped with GPS can pinpoint its location and make on-site assessments without risk to human life.

At one point, the United States Forest Service operated more than 5,000 permanent fire lookout towers, but today that number has dwindled into the hundreds. As this niche job fades even farther into obscurity, let’s take a look at the fire lookout’s most famous tool, and the modern technology poised to replace it.

The Osborne Firefinder

At the most basic level, the job of the fire lookout is to detect and locate the first signs of a possible fire. This boils down to carefully scanning the horizon for signs of smoke, and if seen, plotting the position of the plume on a map and communicating its location to the on-duty fire crews. All a fire lookout actually needs to accomplish this task is a map of the area he or she is monitoring, and ideally a pair of binoculars or a small telescope. Indeed, prior to the 20th century, this would have been the extent of the equipment available.

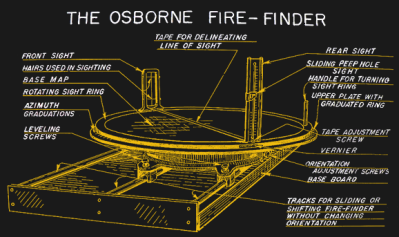

But in 1911, William Bushnell Osborne invented the tool which would ultimately become the hallmark of the fire lookout: the Osborne Firefinder. The device, a type of alidade, featured a large circular map of the surrounding area and a sighting apparatus that rotated above it. Some variations of the Firefinder used what was effectively a rifle scope, but others used a “peep” sight that was nothing more than a strip of metal with a small hole drilled into it. In either case, the operator would rotate the Firefinder until they could see the base of the smoke column through the sights.

But in 1911, William Bushnell Osborne invented the tool which would ultimately become the hallmark of the fire lookout: the Osborne Firefinder. The device, a type of alidade, featured a large circular map of the surrounding area and a sighting apparatus that rotated above it. Some variations of the Firefinder used what was effectively a rifle scope, but others used a “peep” sight that was nothing more than a strip of metal with a small hole drilled into it. In either case, the operator would rotate the Firefinder until they could see the base of the smoke column through the sights.

The center of the circular map represented the location of the tower, with compass headings marked around the entire circumference. When the smoke was sighted in, the degrees of rotation marked by the Firefinder would correspond to the azimuth of the target. This heading could be forwarded to other nearby towers and, assuming they could see the smoke from their vantage point, allowed for triangulation of the fire’s location.

If there were no other towers in the area, or they were unable to see the smoke from their position, the operator of the Firefinder could employ the elevation measurement marks on the sights to estimate distance. With the compass heading and an idea of how distant the smoke was from the base of the tower, crews on the ground would at least have enough information to start their search.

Back to the Future

The Osborne Firefinder was a simple device with few moving parts, and yet when properly set up and calibrated, allowed fire lookouts to locate potential danger with unparalleled accuracy for the era. Realistically, the United States Forest Service didn’t have a better way of pinpointing the location of a fire until the use of aircraft became practical. But even still, the Firefinder was a compelling option as it was cheap and easy to use.

Moreover, the Firefinder went through its own evolution over the years, with new variations steadily increasing its accuracy and utility. These incremental updates culminated with the 1934 version, of which more than 3,000 were manufactured and distributed to lookout towers both domestically and abroad. Incredibly, this version was still being manufactured in the United States up until 1989.

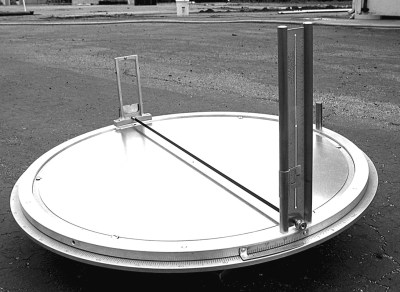

But by the 2000s, there was a problem. With original Osborne Firefinders still in use all over the country, and the supply of spare parts dwindling, the Forest Service’s San Dimas Technology and Development Center (SDTDC) decided to investigate replicating the vintage devices. The various models of the Firefinder were compared, disassembled, and modeled in AutoCAD. Some slight modifications were made based on input from veteran fire lookouts, and prototypes of the new and improved 2003 model Firefinder were built and tested at the Odell Butte and Green Mountain lookout towers in Oregon.

After the successful test program, Palmquist Tooling in California began manufacturing new Firefinders and replacement parts that were largely backwards compatible with the original models. Upgrades for the modern Firefinders included replacing cast iron components with aluminum to save weight, and the addition of nylon bearings to reduce wear.

Eyes in the Sky

Firefinders, whether original Osborne or the updated SDTDC versions, are still actively being used today. Given the fixed location of the tower as a reference point, they give lookouts a simple and reliable way to determine with reasonable accuracy the coordinates of a potential fire. But the reality is that automated systems can do the same job faster and with a much higher degree of accuracy than any human.

Currently, there are a number of different high-tech approaches being used or considered for fire detection. A new space-based system was just brought online over the summer that uses data from several orbiting spacecraft, including the latest GOES weather satellites, to provide continuous monitoring of potential or ongoing wildfires. With updates being pushed out as quickly as once per minute, the system gives emergency agencies a high-level view of the situation in nearly real-time, allowing for efforts to be coordinated far more efficiently than was possible in the past.

But there’s only so much that can be seen from space. To provide a closer view of conditions on the ground without endangering human life, several small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) have been approved for use in and around active wildfires for the purposes of on-site monitoring. These craft can get far closer to the fire than manned vehicles or firefighters can, and provide crucial information on how best to combat it. Similar UAVs proved invaluable during the blaze at Notre Dame cathedral, and represent something of a revolution in close-quarters firefighting technology.

Freaks on the Peaks

It’s undeniable that technology has largely supplanted the fire lookouts at this point. The US Forest Service actually rents out many of the towers as summer vacation cabins now, as the task they were built for has been antiquated by satellites and UAVs. But in the parts of the country where the towers are still staffed with self-identified “Freaks on the Peaks”, the old ways are alive and well.

Even with all the modern technology available, human lookouts can still be a viable option. For one, they’re cheap: most fire lookouts are employed only during the summer months and paid an average of $12 USD per hour. Some of the lookouts have been stationed at the same tower for decades, which gives them invaluable experience with the nuances of the land that can be critical in a crisis. Operating conditions also need to be taken into consideration: UAVs have a difficult time flying in the summer thunderstorms which have been known to trigger wildfires.

Even with all the modern technology available, human lookouts can still be a viable option. For one, they’re cheap: most fire lookouts are employed only during the summer months and paid an average of $12 USD per hour. Some of the lookouts have been stationed at the same tower for decades, which gives them invaluable experience with the nuances of the land that can be critical in a crisis. Operating conditions also need to be taken into consideration: UAVs have a difficult time flying in the summer thunderstorms which have been known to trigger wildfires.

With time, even these advantages are likely to be overcome by newer and more advanced automated systems. But until then, a small army of men and women will still climb their towers every spring and keep vigil over the forest with little to keep them company beyond an Osborne Firefinder that was likely built decades before they were born.

My state has a lot of old fire towers they desperately try to get rid of, but via auction. So they appear on auction ($5 starting bid)… with the caveat that YOU have to come remove them somehow.

It isn’t surprising that they just aren’t getting any bids.

Really? That would be cool. What state is that. Got a link?

It’s Wisconsin, and they auction them off at http://www.wisconsinsurplus.com

I don’t think there are any for auction at this moment, but there will be at some point, I’m sure of it.

I saw several posted just earlier this year near Eau Claire.

I think one would make a great deer hunting shack, but as you said, removal and installation is the killer.

They actually had wildfires in Wisconsin????]

Some of the worst wildfires in the US yes.

Google “Peshtigo wildfire”

But why remove them at all?

It’s a permanent structure with proper foundations AND a path to it…perfect as a recreational cabin. Why not sell them along with the land they’re on, so people can keep them in good shape?

Probably because they’d have to sell the land and if that tower is located in a national park…..

Some parks have been renting them out to hikers too. The problem for a lot of them are they are over half a century old and due to their location maintenance isn’t cheap. I got to hang out at one years ago as part of doing trail work on the north rim of the grand canyon. It was awesome but even back then it wasn’t open to the public due to liability concerns.

They are on public land so they already belong to everybody. They don’t need to be sold they need to be staffed. Not everything has to change–and lookouts do far more than just spot fires. Will a machine greet hikers and perform radio relays or fix a trail or fight a fire? Buzz off about something you don’t know…

Friend of mine bought one, just because he wanted one. Hauled it 300 miles home, then couldn’t get a variance to put it up at his lake property. It sits in a shed.

North Carolina? I’ve been seeing them on the state surplus property auction site for probably a couple years now.

Wisconsin, actually.

My sister was a fire spotter in the St. Joseph National Forest in Northern Idaho for years. She has some interesting stories especially what she did during lighting storms. During them, she sat on a metal stool (really) that had glass telephone insulators on the legs in the center of the tower shack. She knew lightning was going to strike when her long hair would stand out like seen in the Van de Gaff demonstrations with school kids.

That’s interesting, obviously a lightning storm will be a peak time for the need for the fire spotters as well, so they couldn’t retreat from their positions. Do the towers have lightning conductors?

My fire tower veteran sister said that there were lightning rods on the roof of the tower shack and that there were ground straps running from them to ground albeit the legs of the tower were metal. Also ground rods were driven deep as the structure was built ‘On Rocky Top’ as the song goes.

A fire spotter in southern Idaho told me a very similar story back when there was a lookout near where I lived. It sure must have been something to see and feel!

I wonder why, after traveling for miles through the air, lightning would be stopped by the glass telephone insulators. Or were they there for psychological comfort only?

Lightning should not hit you at all if you are insulated from the tower by the glass insulators. You are effectively insulated from the ground, the lightning would hit somewhere else that has a path with less resistance.

The lightning makes its way through the air to the roof of the tower, and at this macro scale does so with complete disregard of the placement of the glass insulators. But once it’s made its way to the roof of the tower, it is left to find the path of least resistance to the ground. It could meander its way around the outside of the structure, or, if not dissuaded by the glass insulators, continue straight down through the poor fire spotter on duty. The insulators cause changes only at the local level; the lightning still chooses the tower whether the insulators are there, or not.

(please excuse the anthropomorphizing)

Disney did something about these, though I can’t remember if it was separate or in the one about smokejumpers. It was a time, tge sixties, when camping and outdoors was getting big.

Michael

I recall seeing a Disney show about that, way back then,

It was probably on the “Wonderful World of Color” or the “Wonderful World of Disney”

Oh yeah, IIRC, it was “The [..] Burn”

The […] was the name of the firewatcher who spotted and responsed to the fire.

Ah! found it!

“The Mallory Burn”

https://disney.fandom.com/wiki/Fire_on_Kelly_Mountain

My father worked for the USFS in the El Dorado National forest. One summer in the early 1970’s he took his crews and a couple of tanker trucks to the lookout at Robb’s Peak to spray the lookout with water to make it appear as if was raining at the end of the filming for a Disney movie which I believe was titled ‘Fire on the Mountain’. I will need to ask him if he remembers this bit of history!

Why bother even selling them when they can be repuposed, if they’re easy to spot, in known locations with a proper path to them surely they’re ideal for emergeny shelters if anyone gets into trouble out in the parks. Just leave a small amount of emergeny supplies and a singalling method in them. All you’d need to to is go up there every once in a while to check on their condition.

I assume they need some level of upkeep so they are safe, and don’t fall down, and nobody wants to fund that, hence the need for removal.

But yes, they are otgerwise more valuable in place, precusely for the reasons you mention.

At least lighthouses have often been sold off, either to individuals who move in, or non-profits that use then for museuns.

Michael

Vandalism…

As a kid, I always wanted to be one of the fire tower lookouts when I grew up.

I’ve always loved the outdoors. My wife and I met at a YMCA outdoor summer camp as kids. Today we aim to hike the backcountry of at least one of our Nation’s National Parks every year.

I imagined getting the chance to get to know the countryside like the back of my hand; seeing Hawks or Eagles gliding overhead, or bears wandering through the bush below looking for berries.

Today, as a recruiter in “smart industry” I am nostalgic as I see automation bringing this niche job to a close.

Robotic Park Rangers. Bear-proof.

It is probably because it is re-purposed military gear,

but I think the Electric Falcon should be painted a contrasting color to the forest…

In Poland watch towers are normal, on EACH forest

I used to search out abandoned firetowers to climb them for fun, camping trips and abseiling practice etc. I don’t think Ive ever been in one that didn’t have a huge stack of pornography under the desk. Yup those old towers have sure seen some things.

How about tethered balloons?

Sounds like you’re a century late with this suggestion. They built towers for people to stay in instead.

We currently have downward-looking radar systems carried by tethered balloons supporting drug interdiction efforts in the American Southwest. I used to work on the radar systems. Tethered balloons are current technology.

Can find them on Google also.

@radaereilly Do you know what are they filled with, helium or a helium hydrogen mixture?

My guess would be both gases. It’s cheaper, provides more lift, and in the unlikely event it explodes, no one is going to get hurt.

And then there’s the whole issue with forests being way too dense due to too strict fire control. Before humans interfered, forest fires were common, but due to that fact, less encompassing, as the forests were naturally sparser, meaning that fire didn’t spread as extremely as it does now.

This is indeed a very large problem for a lot of forests.

Then a lot of the vegetation in a forest also benefit from the occasional fire sweeping through.

Though, with large accumulation of material in a forest that hasn’t seen much fire, then it usually burns far too harshly for it to be much of a benefit to anything.

This is a reason a fair few countries do controlled burns in their forests, and also clear out excess debris every now and then. In the end, forest fires is an event most forests used to see once every 5-20 years.

Smokey has changed his phrase, to acknowledge that he was talking about careless people.

The ancestors used to do controlled burns in the Northwest, the distant cousins still do. I saw a notice months back about one, including the plans to make it safe.

Michael

For the forestry service, this is a no-win situation. If they start prescribed burns that go out of control, they’re liable. If they cut firebreaks that wildfires jump, they get sued for negligence. If they let wildfires burn, they get sued. They face the lowest liability by doing what they’re doing: don’t do anything until a fire starts, then try hard to stop it.

I have always wanted to do this since I read Dharma Bums by Kerouac.

It’s cool to see the technology involved with this.

It was a practical desire too because I find humanity insufferable most of the time and would have been perfectly fine living alone months at a time in the wilderness and getting paid for it.

Well, there are remote fishing camps in northern Canada that are open for eight to ten weeks in the summer. They need winter caretakers to prevent vandalism and theft. You don’t have much power, but if you don’t mind living alone in the cold for ten months a year, it does pay. I’ve been to one such place; the winter caretaker spends about a month after arrival chopping firewood for the time to come.

They still use them here in the Bay Area.

And here in San Diego County, CA. Mostly by volunteers from the FFLA.

@Shannon: At the very least, the two I’ve been two in WA (Kelly Butte and Mount Fremont) have clear grounding lines made of very heavy gauge wire from a point on the top, descending below the exposed rock to where they’re stapled into the earth.

Then again, one of them’s clearly quite frayed from people walking on it.

There is also a rapidly expanding network of fire cameras in the West at: http://www.alertwildfire.org/

They are used for fire detection and response coordination. It mostly uses communications and microwave towers already common on hilltops all over. Those locations feature robust power backup, good sight lines and network access.

Any fire in California often has multiple cameras focused on it.

That’s really neat! I spent about 20 minutes just looking around at all the cameras because I’ve never been on that side of the US.

There is some beautiful country shown off by those cameras. The Tahoe section is one of the best; the winter views there are great. Armchair travel!

Also, you can watch time lapse videos by right clicking on the main view.

Oh I need to check that out!

This might not be a bad idea, those guys can get kind of weird up there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JQD7ArOHpQI

Now I want to play that Firewatch game again

Yeah it’s probably the closest many of us will get to the experience of being in a tower.

Sorry to see them go. They make wonderful temporary places to put radio repeaters during fires in the area.

~30 years ago, a fire tower in Colorado was converted to an antenna farm. Space on the tower top rented for antennas, and a shack down below for the transmitter/repeaters.

Reminds me of Amateur Radio Repeaters in California I was just reading on Reddit as I saw the Youtube algorithm suggest watching a video regarding. Seems to align with firefighting also.

Seems to me they should be renting them out to cell phone companies. May not be that much traffic, but for most of their locations would come in handy in a wilderness emergency situation.

It might make those lonely Rangers lives a little more pleasant as well.

Now that is an excellent idea. The only problem I see is power. Solar just doesn’t cut it for cell towers. I don’t know if these all had power running out to them, but it would certainly be a requirement.

None of the ones I’ve visited have had power going to them or within many miles of them.

The one I worked in for two seasons here in California had an inverter system in it for power — a couple of lead acid batteries, a 1 kW inverter, and a few solar cells on the roof to charge the batteries. Our radio system inside ran from 12 VDC. We had enough power throughout the day as very little inside depended on AC power.

I think with today’s solar technology it should be possible. Cell towers need battery back up anyway. You just need space for the panels. Then design the backup batteries somewhat larger and/or think about additional diesel backup.

Maybe in the days of the old AMPS system last century, but these days, cell towers are intentionally located down low, to cover a relatively limited area, so that a particular frequency may be reused for other cell sites not so far away.

That’s useful in densely populated urban areas. In rural areas you still want greater coverage.

They built 15 new fire towers in my state this year.

https://stateimpact.npr.org/pennsylvania/2019/05/10/with-new-lookout-towers-pennsylvania-goes-old-school-to-detect-wildfires/

I love how they’re made of wood =P

You can tell the direction of the fire from which way it falls.

It seems rather ridiculous how anxious people are to replace humans and simple fairly, low tech solutions which are presumably effective enough most of the time with entirely automated high tech solutions. No one ever seems to consider the possible downsides of the tech solutions, just the immediate positive benefits and possibly short term cost reduction.

My Lookout will never be replaced by technology. The locals would never allow it. It functions not only as a fire lookout, but as a communication beacon for the entire community. As long as it stays in one piece, it will be manned. Technology will never replace the efficiency of the human factors.

What state are you in? What is the name and location of your tower?

Instead employee people to cut fire lines in the woods and areas around the power lines.