For many of us, the term “wearable technology” conjures up mental images of the Borg from Star Trek: harsh mechanical shapes and exposed wiring grafted haphazardly onto a human form that’s left with a range of motion just north of the pre-oilcan Tin Man. It’s simply a projection of the sort of hardware we’re used to. Hacker projects are more often than not a mass of wires and PCBs held in check with the liberal application of hot glue, with little in the way of what could be called organic design. That might be fine when you’re building a bench power supply, but unfortunately there are not many right angles to be found on the human body.

Thankfully, we have designers like Sophy Wong. Despite using tools and software that most of us would associate with mechanical design, her artistic eye and knowledge of fashion helps her create flexible components that conform to the natural contours of the wearer’s body. Anyone can take an existing piece of hardware and strap it to a person’s arm, but her creations are designed to fit like a tailored piece of clothing; a necessary evolution if wearable technology is ever going to progress past high-tech wrist watches.

During her talk “Made With Machines: 3D Printing & Laser Cutting for Wearable Electronics” at the 2019 Hackaday Superconference in Pasadena, Sophy walked attendees through the design process that she’s honed over years of working on wearable creations. Her designs start in the physical world, occasionally taking the form of sketches drawn directly onto the surface of whatever she’s working on, before being digitized and reproduced.

Featuring graceful curves and tessellated patterns that create a complex and undeniably futuristic look, many of her pieces would be exceptionally difficult to create without modern additive or subtractive manufacturing methods. But even still, Sophy explains that 3D printers and laser cutters aren’t magic; these machines free us from time consuming repetitive tasks, but the skill and effort necessary to create the design files they require are far from trivial.

Expectation vs Reality

Early in her talk, Sophy compares her experience with 3D printers and laser cutters to a tool that’s perhaps a bit less commonly seen in the workshop of the average Hackaday Supercon attendee: a sewing machine. She explains that when she first got her sewing machine, she imagined herself sitting down and powering through projects with ease. But in reality, the majority of her time ended up being spent on design and preparation. When she finally was ready to use the sewing machine, the project was already in the home stretch.

In the same way, she says new 3D printer or laser cutter owners need to understand that there’s a considerable amount of work to be done before you’re able to just push a button and receive your final product. For as much physical labor these machines save, they add an equal amount (if not more) time on the design and software side of the equation.

Which is fine by Sophy, as her background in graphic design means she’s already accustomed to bringing her ideas to life digitally. As she says several times through the presentation, machines that require some element of CAD to operate “speak her language”. But that doesn’t exactly mean it was an easy transition. Sophy was well versed with 2D tools, but bringing things into the third dimension took some getting used to.

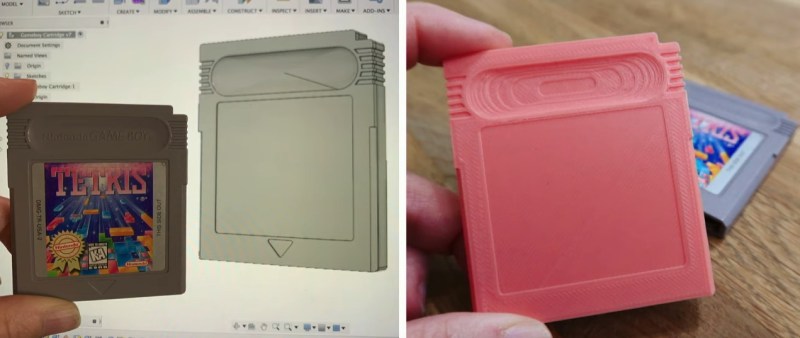

Her advice for those starting out with 3D design is to learn by doing. Watching a tutorial online and duplicating the steps laid out for you simply isn’t enough. In her case, she challenged herself to design something in 3D every day for a month so she could become comfortable with the workflow.

Sometimes she would design logos or little toys, and other times she would recreate objects she found around the house. It doesn’t matter what you create, as long as you become confident enough with the tools that you’re able to quickly and accurately articulate your ideas to the machine sitting on your bench.

Pushing the Boundaries

Most of the 3D printed parts we come across take the form of electronics enclosures, brackets, or customized adapters. These utilitarian pieces are designed hastily and often given little thought, as the hacker would rather spend their energies on more exciting elements of the project.

But once you understand how to speak the language of your equipment, and especially if you find delight in the CAD process, you can start to truly wring the most of out of its unique capabilities.

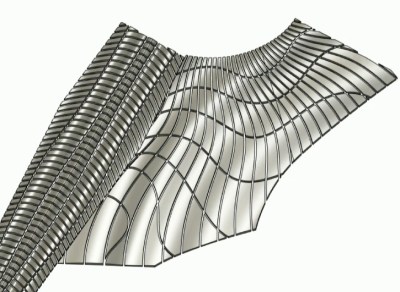

The things that Sophy has been able to produce on her Creality CR-10S, generally considered a budget 3D printer, are nothing short of phenomenal. By stretching a thin mesh over the printer’s bed during the print, she’s able to link hundreds of individual elements into one cohesive fabric. The carefully spaced separations between each element give the fabric unique properties, such as changing shape depending on which way it is folded or flexed.

During her talk Sophy mentions that one of her recent projects, comprised of thousands of individual 3D elements, was so complex that she needed to move over to a more powerful computer just to keep her CAD software from locking up. She explains that at this point, it’s becoming clear that tools developed for traditional CAD will have difficulty keeping up with the intricacies of her printed fabrics on a large scale. It may be that further development of printed garments will require a whole new suite of CAD tools to cope with their unique design requirements.

Follow What Moves You

Sophy, along with a number of other talented and creative individuals in the community, is working on the very cutting edge of 3D printable textiles. These projects are the first steps towards a technology which one day may become part of our daily lives. At least for the more fashionable among us, anyway.

But even if being wrapped up in skin-tight PLA isn’t exactly your kind of thing, Sophy’s talk is inspirational because it shows just how much the individual maker and hacker is capable of with affordable hardware and the determination to put it to use. Her advice for becoming more confident in your tools and adopting an iterative design approach is valid no matter what you want to build. Who knows? If you follow her example, you might be up on the Supercon stage next year telling us all about it.

Excellent Sophy,

let me in

I came expecting “how to sew LEDs into clothing” and was gladly disappointed. Keep up the excellent work Sophy!

Anecdotes are always good, but what exactly is novel here? Am I missing something?

I think you’re in the wrong place.

I guess you missed the part where she’s designed clothing which is 3D printed and yet also flexible and movable.

For now this is fashion, but I can easily imagine this being used to make a breathable daily use ‘armour’ for police or military use.

“organic design”

Oxymoron of the day.

Not if you’re a creationist, I suppose.

I work in software development, I’ve seen plenty of ‘designs’ which have suffered from being organic. For me organic or evolutionary design is typified by complexity increasing and increasing until something gives way and a either some part of the evolved design is simplified or the design dies and its niche is filled by something else. I would not recommend it as a software methodology.

I don’t know, Sophy, my favorite part is still where I push the button, and cool shit pops out.

But I hear what you’re saying – it wouldn’t be nearly as cool if that was all there was to it.

That blue tape scanning process for making patterns is genius. I will use it.

“For many of us, the term “wearable technology” conjures up mental images of the Borg from Star Trek: harsh mechanical shapes and exposed wiring grafted haphazardly onto a human form that’s left with a range of motion just north of the pre-oilcan Tin Man.”

And here we thought it was when the government bugged our clothes.

How true the concept of the sewing machine/ printer/laser cutter / lathe/ saw are almost end of the process.

No matter how fancy the machine it is nothing without the planning and design.

That outfit looks like it’s made of shaped pieces of photovoltaic cells. That would be ideal for charging up your phone and other gear while walking around.

Except a lot of it is at the wrong angle to work as a decent collector.

The technique of using splints to control fabric shape and flow must be worth a patent. Or at least algorithms for predicting/deriving that would be – it’s the sort of thing I imagine coming out of Disney research.

Seems derivative of boning, using shaped pieces of whalebone (baleen) in women’s clothes in the 1800’s through early 20th century to control shapes.

As I read this the underwire in my bra pokes a suggestion that boning did not end in the early 20th century.

Why would anyone want to wear something so clumsy and fragile like this? It wouldn’t even survive a coffee spill let alone a single washing machine cycle. Anyway, calling it the “future of wearable” is beyond silly.

None of that detracts from the fact that it does look really awesome.

The same criticisms could be made of the first transistor prototype, but they were indeed the future of electronics, and a TO-92 would now survive a machine wash and coffee.

The same could be said for anything you’d see on the runway at a high-end fashion show. We’re not talking about day-to-day wear, we’re talking about the cutting edge of fashion and design.

Waiting to see completed ensemble. Bodice is gorgeous and can only imagine how elegantly it moves with motions of the wearer. Mostly due to no freaking vid.

More Sophy:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DzfLiMt1qqc

Cat glove. Ha. Flappy suit. Chuckle.

In case yall cant decode half screen link to her hackspace book:

https://hackspace.raspberrypi.org/articles/wearable-tech-projects

It’s not only Sophy’s work. I liked it.

I seldom have time to watch video links,

I am glad I found time to watch this one.

( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)