If you haven’t noticed, this is an absolutely fantastic time to be a hacker. The components are cheap, the software is usually free, and there’s so much information floating around online about how to pull it all together that even beginners can produce incredible projects their first time out of the gate. It’s no exaggeration to say that we’re seeing projects today which would have been all but impossible for an individual to pull off ten years ago.

But how did we get here, and perhaps more importantly, where are we going next? While we might arguably be in the Golden Age of DIY, creative folks putting together their own hardware and software is certainly nothing new. As for looking ahead, the hacker and maker movement is showing no signs of slowing down. If anything, we’re just getting started. With a wider array of ever more powerful tools at our disposal, the future is very literally whatever we decide it is.

In her talk at the 2019 Hackaday Superconference, “The Future is Us: Why the Open Source And Hobbyist Community Drive Consumer Products“, Jen Costillo not only presents us with an overview of hacker history thus far, but throws out a few predictions for how the DIY movement will impact the mainstream going forward. It’s always hard to see subtle changes over time, and it’s made even more difficult by the fact that most of us have our noses to the proverbial grindstone most of the time. Her presentation is an excellent way for those of us in the hacking community to take a big step back and look at the paradigm shifts that put such incredible power in the hands of so many.

Hacker History

To get the whole picture, Jen starts all the way back in the 1970s with the Homebrew Computer Club. In those heady days, some of the biggest developments in home computing were literally taking place in hacker’s garages. By the 1980s, the GCC project was in full swing, giving hobbyists their own toolchain to develop and debug software without having to purchase an expensive license. A few short years later, Linus Torvalds made his now iconic post on the comp.os.minix newsgroup looking for feedback on the free “hobby” operating system he’d been working on.

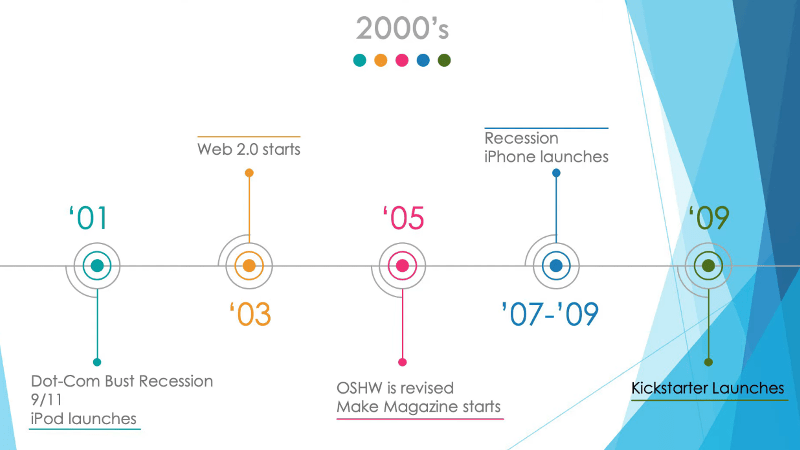

Moving on to the 2000s, we see the rise of Maker culture. Companies like SparkFun and Adafruit pop up to provide high-tech components for DIYers, Makerbot makes it possible for the average consumer to 3D print parts at home, Kickstarter provides an influx of cash to anyone with a good idea, and Maker Faire proves there’s a huge number of people out there who are curious about building things themselves. The stage is set for another revolution in how hardware and software is created, and this time it’s on a scale that would have been inconceivable a few decades prior.

All of these milestones have been critically important for our community, and when presented in a timeline like this, the natural progression towards bigger and better things is clear. But what Jen is really trying to illustrate by plotting them all out is not so much what happened, but when it happened.

The Circle of (Tech) Life

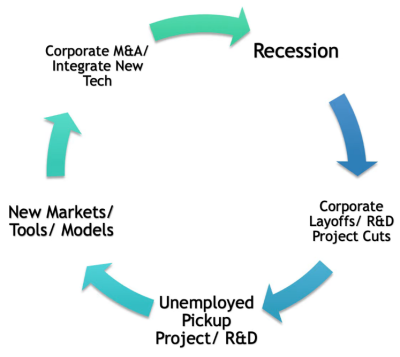

As Jen goes on to explain after presenting this hacker history lesson, many of the formative events that put us where we are today happened during a recession. It seems that when the economy is doing poorly, hackers and makers thrive.

The rationale for the big events is easy enough to understand; when you’ve got a lot of really smart people that are unemployed or underemployed, they’re more likely to throw themselves into the hobby projects that they otherwise might not have had time to work on. For the DIY crowd the reasoning is even more blunt. When the money’s tight, people are more willing to repurpose things than buy new.

The rationale for the big events is easy enough to understand; when you’ve got a lot of really smart people that are unemployed or underemployed, they’re more likely to throw themselves into the hobby projects that they otherwise might not have had time to work on. For the DIY crowd the reasoning is even more blunt. When the money’s tight, people are more willing to repurpose things than buy new.

But history also tells us that this period doesn’t generally last very long. Pretty soon, the big corporate players get wind of all the incredible things coming out of garages and hackerspaces, and start buying up ideas and hiring up the talent. Once part of the corporate machine, the innovation invariably slows back down, things start getting expensive, and the stage is set for the cycle to start all over again once the money dries up.

If we look closely enough, some of the cracks are already starting to form. Maker Media is struggling to rebrand itself, putting the flagship Maker Faires on indefinite hold. Companies like Facebook, Microsoft, and Samsung are aggressively scouring the community for ideas and talent they can use for their respective virtual and augmented reality projects, which one could argue has slowed the development of hacker-friendly AR and VR headsets.

Preparing for What’s Next

The “Great Recession” that brought us all those incredible maker advancements in the 2000s is now over, and we’re currently enjoying a period of exceptional economic growth. Companies are expanding and buying up ideas, and for those who recognize these sort of trends, there’s an opportunity to cash in.

Jen says that companies today are watching sites like GitHub and Hackaday.io closely for the next great idea, and will often know all about your capabilities before you even agree to an interview. They might be a little more cautious to write the big checks than they were during the last big boom, but the skilled operators and the good ideas are still going to get recognized.

But of course what goes up must come down. Many economists think that we’re only a year or two away from the next downward trend, putting the potential for more layoffs and cautious spending on the horizon. Some even think it will hit before the end of 2020. So if you get a job with that dream startup in the next few months, don’t be completely surprised if it doesn’t last very long.

The plus side of all this is that if we are looking at another recession in the near future, then we’re also likely to see some new developments in the hacker and maker scenes before too long. If the last recession launched the technologies and companies that have allowed us to operate in this hacker utopia for the last few years, we’ll admit to being more than a little interested in seeing what the next one could bring.

“If you haven’t noticed, this is an absolutely fantastic time to be a hacker. ”

The good kind.

The video was ‘consumed’ along with my lunch. Nodding my head in agreement with her core thesis that recessions (at least the previous three) begat innovation. Interesting and surprisingly insightful for a younger engineer (that is not a slight to youth – I was much less useful at her (assumed) age when compared to the current kids no long out of school).

As for her predictions – am not certain that she listened to herself, as few engineers do (myself included). Outsourcing, failure to mentor and train technical staff, loss of control of (virtual) supply chain, consolidation of data into a few international companies (eg, Amazon, Google, MS), and other things that she mentioned earlier in the presentation would seem to predict a future of diminished possibilities for us common engineering folk.

Speaker chiming in. Much appreciation that you spent your lunch listening.

As someone blessed enough to be working on their third decade in tech, it’s nice when someone thinks you are young because tech values it. This last recession didn’t affect me like it did others but the lack of formal mentorships and prospects have meant we have to take care of our growth as you pointed out.

As I mentioned early in the intro, this turns out to be a huge subject to narrow down in a few minutes. I wanted to give some light in the tunnel because the overwhelming coverage for the US has been a long dark tunnel.

Narrow-mindedness.

https://www.zdnet.com/article/why-are-engineers-so-narrow-minded-new-research-has-an-idea/

Of course, this is forgetting the fact that “unemployed hackers” don’t have the resources to pull off fundamental research – they’re mostly relying on existing and well-known (already cheap) technology that they’re re-purposing for novel tasks.

This sort of “re-inventing the iPhone” does not drive the big picture of technology and economics, because it is relying on innovating on stuff that already exists. The age of inventing new stuff in a shed by yourself is 200 years past, or at least exceedingly rare.

Citizen-science relies on re-purposing technology.

Calling it by a different name doesn’t make it different.

Or, like they say, invent a better mouse trap and the world will beat a path to your door.

But that’s just re-distributing income. The old mouse trap was almost as good, and nothing fundamental has changed.

Any other Martin Armstrong blog readers?…

No mention of the role of AliExpress? With all due love to Adafruit, Sparkfun, et al., some of my bigger projects would simply have been impossible for me (a retired guy) if I couldn’t buy dirt-cheap components in bulk from China.

And don’t you think that is part of the problem?

Sure, being able to buy stuff cheap is good, but the fact that we are now seemingly addicted to that cheap stuff, is a problem, as it points to the law of diminishing returns, it essentially means that the profits are too low, and the whole thing only works because somebody else is making up for the difference, which begs the question, for how long?

Sure… but AliExpress, Banggood etc just _sell_ cheap stuff. Adafruit, Sparkfun, Arduino and others have contributed greatly to knowledge, support and infrastructure. They have also often created new products that make specialized parts more accessible (and then 10 Chinese companies clone them, and they show up for cheap on AliExpress etc…)

As an almost-retired guy, I buy quite a bit from China too… but I’ve also donated to companies like Arduino, and other open-source projects, for providing the toolchains and communities.

A few weeks after I delivered this talk, this excellent podcast on “Home Innovation” was released.

http://freakonomics.com/podcast/home-innovation/

I’m sorry but this is all way over-hyped. The companies mentioned (Adafruit, Sparkfun, Makerbot) are all okay, I ain’t got no gripe with them, but I don’t think they are doing anything particularly technically innovative. Innovative marketing, maybe, but don’t overstate it.

What they are doing is supplying the bits & bobs that the hacker community uses. They are one step above, in terms of integration (like breakout boards) than Digikey and Mouser. Please note I use all of them for my projects.

They’re also publishing educational materials that are more approachable (at least for me) than what was out there before, and it’s free!

What they are doing is great, I’m all for it, but I just don’t buy the idea that what comes out of the ‘maker movement’ is a major factor in economic boom/bust cycles, or even in technological advancement.

No doubt some good stuff comes out of it (possibly indirectly) but a lot of the innovation still takes place in company and university labs, and a lot of the really good stuff is closed source (trade secret or patented).

A lot of the Arduino etc. business is just deliberately dumb in order to hook you up to their ecosystem. The point isn’t to teach you electronics, or to read datasheets, but to simply provide you with a library and a code example, and tell you to plug A to B without telling why.

Though they then omit all the data sheets and details, so you’re reliant on them to tell you what the thing is.

I was looking at a servo and they wouldn’t even tell how much current it needs, or the part item number, or any other information. I had to take the model number off of the product photo off the page and google the original manufacturer.

I don’t watch videos, so I sure don’t know what’s she’s saying. But the blurb here is full if buzzwords, but doesn’t give a goid imoression.

If a recession causes innovation, then why is this only about the recent recession?

Why not use the example of the early seventies receission? Change happened then, but I have no idea if the recession helped or hindered that change.

Or take the depression of the thirties. I’ve read that hams, probably representing the bulk of “electronic hobbyists” , were resourceful, lacking money but having lots of time. But does that translate to innovation? It probably laid a foundation for radio/electronic skill when WWII came along.

But even aside from that, the notion of a “maker movement” is odious, since it sounds like a new thing, but people have always made things. To ignore that is to fall into a trap that “this is the best time”. The arrival of cheap ICs decades ago was a big thing, so was microprocessors. Radio changed a lot in the early years, precisely because it was new. WWII surplus was cheap and plentiful for decades, giving many access to things they couldn’t otherwise afford. Once you start from the now, it makes me question how deep the study has gone.

Just a small observation – in the early 20th century, not just amateur radio, but all radio itself was a hobby; commercial receivers were expensive, and the field was changing so fast that a good homemade receiver could compete with many commercial ones. And there was experimentation with antennae etc. I also think that the deprivations of the 30s and WW II sustained the interest in building and tinkering with receivers. (I’m a nut for tube regenerative receivers)

I’m not gonna bash the young’uns for not acknowledging that the field existed long before “hackers” and “makers”. Too much of my current personal and professional activities are tied up with opensource projects and community-supported hardware and software.

Test equipment gets quite cheap during a recession. In 2008, I managed to pick up an Agilent 1 GHz 4 ch mixed signal oscilloscope for about 5k with a set of 500 MHz passive probes. It was a demo unit of a then current model with a list price around 25k. This was from an official distributor too.

When the next recession hits, I have my heart set on getting one or two Keithley sourcemeters. You know.. for those times you absolutely need to measure resistance using 10 amps of excitation current.

There seems to be short memory here.

In the old days, we had local stores where we couod go to get parts, and I’m not talking Radio Shack. As transistors and ICs took over, it became harder, the old places not adjusting or outright closing down, and distributors didn’t want to deal with hobbyists who most likely wanted to buy onky a few items. So a new wave of places took over, usually mail order. They’d stock key components, tye ones that were used in projects and/or sold well. Soke, like MITS and Digi-Key, didn’t sell parts, they sold kits, so you coukd get everything you needed to build that project in tye magazine.

Digi-Key then started selling some components, and eventually became really big. There seemed to be a shift, a new wave of distributors wiling to deal with hobbyists.