Satoru Iwata is perhaps best remembered for leading Nintendo through the development of the DS and Wii, two wildly successful systems which undeniably helped bring gaming to a wider and more mainstream audience. But decades before becoming the company’s President in 2002, he got his start in the industry as a developer working on many early console and computer games. [Robin Harbron] recently decided to dig into one of the Iwata’s earliest projects, Star Battle for the VIC-20.

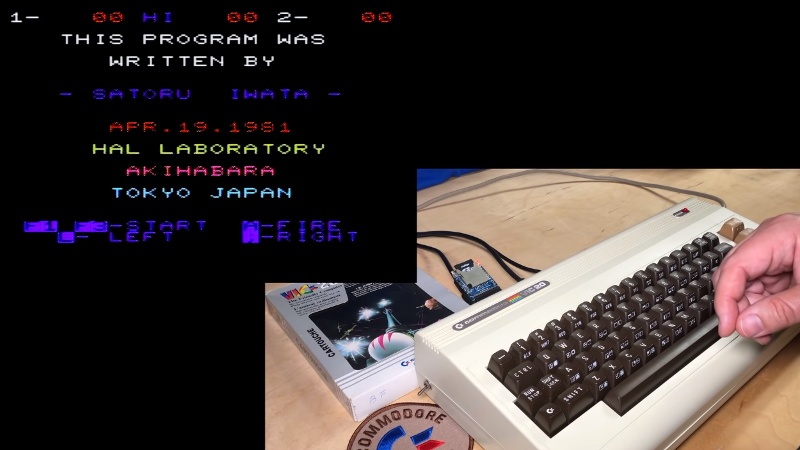

It’s been known for some time that Iwata, then just 22 years old, had hidden his name and a message in the game’s source code. But [Robin] wondered if there was more to the story. Looking at the text in memory, he noticed the lines were actually null-terminated. Realizing the message was likely intended to get printed on the screen at one point during the game’s development, he started hunting for a way to trigger the nearly 40 year old Easter Egg.

As it turns out, it’s hidden behind a single flag in the code. Just change it from 0 to 1, and the game will display Iwata’s long-hidden credit screen. That proved the message was originally intended to be visible to players, but it still didn’t explain how they were supposed to trigger it during normal game play.

That’s where things really get interesting. As [Robin] gives us a guided tour through Star Battle’s inner workings, he explains that Iwata originally intended the player to hit a special combination of keys to tick over the Easter Egg’s enable flag. All of the code is still there in the commercial release of the game, but it’s been disabled. As Iwata’s life was tragically cut short in 2015 due to complications from cancer, we’ll perhaps never know the reason he commented out the code in question before the game was released. But at least we can now finally see this hidden message from one of gaming’s true luminaries.

Last time we heard from [Robin], he’d uncovered a secret C64 program hidden on a vinyl record. With his track record so far, we can’t wait to see what he digs into next.

Probably for similar reasons to the first easter egg which appeared in Adventure for the Atari 2600. Atari’s owners demanded that all their developers be anonymous (and therefore interchangable and cheap), so the devs got sneaky. Wouldn’t surprise me if the easter egg got discovered before release and the publisher insisted it be disabled.

That used to be quite a common insistence across several areas (not just games). We usually found a way though – people are easily bought by having their name added to the roll call :-)

Many years ago I was working on a interactive disk that was given out to customers of a realtor. I wanted a way to prove that I wrote the software so I put a similar screen. It was activated by typing my name when you were on one of the screens in the presentation. As fate would have it, I was showing my boss something on my computer and had that page running in the background. I think that I was logging into my email, which involved typing my name. Even though the program didn’t have focus, it still caught those keystrokes and started displaying my easter egg. My boss wan’t happy about that and told me to remove it. I just ended up burying it deeper so that it wasn’t easily accessible. Maybe something similar happened here too?

It picked up the keystrokes even though it didn’t have focus… so you built a keylogger? And when your boss called you on it, you just hid it instead of removing it.

Sometimes hidden key combinations with a purpose for development are also left in.

If you have experience with novell netware from 20 years ago you maybe know the key combination ctrl,alt leftshift, ctrl,alt,rightshift esc. You can do it with two hands but its difficult.

If entered on the server the memory is dumped and the system hard resets, always funny to do at a fair when salesmen are bragging about robustness.

Dang, wish I had known that back in 1995 when I took over IT duties at the small factory I worked at with minimal training (and minimal pay). I was young and dumb (but computer literate), and managed to keep the network alive and ticking until I left that festering hole a couple years later. That particular trick would have been useful for getting the server upgrades we drastically needed. The GM at that factory was a real tightwad, and a real jerk. For example: He made me replace our dying SCSI drives with a pair of cheap PATA IDE drives despite my protests, and then got on my case for how long file transfers were taking afterward! It might have been useful for convincing him to allow me to get some up-to-date hardware. (“Look, the server keeps doing that. We need a new one…”)