When it comes to the Internet of Things, many devices run off batteries, solar power, or other limited sources of electricity. This means that low power consumption is key to success. However, often these circuits draw relatively small currents that are difficult to measure, with plenty of transient current draw from their RF circuits. To effectively measure these low current draws, [Refik Hadzialic] built a cheap but accurate current probe.

The probe consists of a low value resistor of just 0.1 Ω, acting as a current shunt in series with the desired load. By measuring the voltage drop across this known resistor, it’s possible to calculate the current draw of the circuit.

However, the voltage drop is incredibly small for low current draws, so some amplification is needed. [Refik] does a great job of explaining his selection process, going deep into the maths involved to get the gain and part choice just right. The INA128P instrumentation amplifier from Texas Instruments was chosen, thanks to its good Common Mode Rejection Ratio (CMRR) and gain bandwidth.

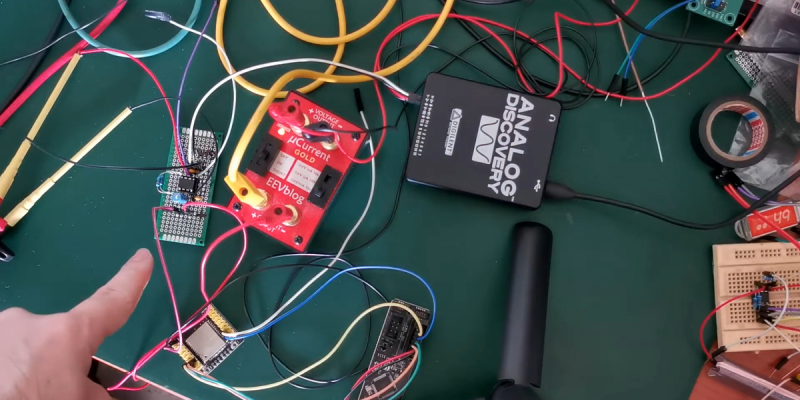

The final circuit performs well, competing admirably with the popular uCurrent Gold measurement tool. While less feature-packed, [Refik]’s circuit appears to perform better in the noise stakes, likely due to the great CMRR rating of the TI part. It’s a great example of how the DIY approach can net solid results over and above simply buying something off the shelf.

Current sensing is a key skill to have in your toolbox, and can even help solve laundry disputes. Video after the break.

cheap? if you consider samples as a viable sourcing option then yes.

gets the job done? Yes, and that should be the end of it.

good way to compare noise? No, not at all, the results are meaningless. A conclusion cannot be drawn from that setup.

And I also consider the uCurrent from Dave as a diy effort, although much more polished, and available commercially.

You know exactly what to expect from a uCurrent. No need to reinvent the wheel unless need be.

To be fair, sometimes you want your project to do the current measuring – sure, as presented, it’s mostly an exercise in externally measuring the current of a DUT, but what if your circuit itself was to measure and log or sum production or consumption data, say because you don’t want to dedicate your µCurrent to the task, or you’re making 5 (or more) of something.

I have similar current sensors (though with an AD620BAZ InAmp). Cheaper for me to integrate that into my project than have half a dozen µCurrents sitting around.

I use current sense resistors for characterizing our new chip designs at work all the time. They do a great job. Most nice multimeters allow you to manually range them to a very low range so your measured voltage is a decent part of the whole range. The unit I usually use has a low range of 100mV with a 3uV sensitivity, and if I set it up to average 100 readings each time I request a measurement, I get results with more precision than we need. We usually design boards with relays to switch in a 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 ohm resistor depending on what we need. It’s really valuable for test setups where amperages will exceed what multimeters can directly measure, but also need good low-current measurements in the same test. It’s important to get precision resistors with fairly linear, low coefficients of thermal variation, although you can cal those out with known loads.

Ok. So he mentions it is not isolated so AC should be done very careful. So how would you isolate a signal like that? Transformer? The signal coming out is analog not digital but would it change enough to excite a transformer output.

Depends on what you are doing with the signal. i.e. analog or digital.

Digital would be throwing an ARM uC with 12 or better (I had one with 16) bits ADC, do all the math for signal processing then spit back the results in digital. Keep the uC side non-isolated, powered by good old transformers. Isolation for results is easy with either Wifi or Ethernet (1000V isolation) or even isolated USB or low tech opto serial.

Using a INA128 for this? Jeepers.

What are they thinking? Why use a $0.50 part, when a general-purpose $10 part requiring precision external parts will do?

I mean, it’s not like there are not a huge number of very cheap parts specifically designed and optimized for this exact task, though finding them might involve having to use Digikey’s new search facility.

I use in-amps a lot and have hundreds sitting around in prototypes and such, multiple types. I can pull one off in seconds. So just mind that for some people, the “cheaper” option would be more expensive, since once you have to order something you spend money and your time dealing with it. You can find lots of eBay “junk” with heaps of good precision parts on them as well, if you’re that cost sensitive in a hobby setting. As for those “$0.50” parts: current sensing applications are not special. If there were $0.50 current sensor amps with specs as good as, say, AD8221 has with bipolar supplies, nobody would buy the AD8221 – it’d be a waste of money. A flexible current sense amp has a name: instrumentation amplifier. It’s not like the low voltage across a resistor is special because it comes from a current shunt. There’s lots of marketing nonsense where they sell “cut-down” in-amps as current sense amps for niche cost sensitive high volume applications (eg specifically unipolar or ground-level common mode etc). Those are all just in-amps though, just specialized and they make sense where volume and cost play a role. In a lab tool like uCurrent, none of it matters much, because eventually the time of anyone who uses it is worth way more than the tool, and having a tool with higher-end specs is worth more than worrying about a tool that runs out of steam earlier. In other words: this article showed how anyone who doesn’t have uCurrent would do it, and the better results are not unexpected. As for those “precision parts” for the in-amp: any metal foil resistor will do really, as long as you don’t let it get hot. So I don’t know what you’re talking about. And what, you think uCurrent runs on carbon comp resistors, lol? It has more precision parts in fact that a boring in-amp needs :) uCurrent is a good tool, but it doesn’t make sense for everyone.

Sometimes the narrow-mindedness and negativity of commenters amazes and at the same time shocks me.

A guy does something in a way he thinks is good or simply he has the tools/parts for and shares his info/knowledge about it. For free.

And here comes the “duh, µCurrent is just a DIY thing” guy and a “why use X when you already got a µCurrent device” guy chimes in. And using samples to try something? Pure evil…

What the… Get a grip and accept that people are doing things their way!

The guy postulated a problem, took a part he had laying around, used it exactly as described in its datasheet to solve the problem, and did a nice writeup describing the design process. Kudos. Great educational tool, and I’m sure he learned something doing it. All good.

But said part is essentially obsolete, and has a better, cheaper direct replacement.

The approach used is right out of a textbook, or the 25-year-old datasheet. Fine as it is, but it has a number of serious faults (like it can’t measure the current in the supply rails, so *requires* a separate supply, and several other issues)

Not faulting the original author too harshly for choosing that route (a part on hand that will do the job…). But there are much better, cheaper modern approaches available, and HaD should not be holding a 25-year-old approach up as an exemplar of anything but historical interest or a teaching tool.

Who errantly informed you that Hackaday is a site devoted to covering tasks having been done with technical excellence or perfection being the goals? “Hack” is in the very name, and if you understood the history or the culture at the most basic level, it’d be obvious to you that using what’s on-hand, even if for the challenge alone, is where this audience looks to measure merit. I’m sure there’s an IEEE journal to satisfy your needs.

I’m not sure what’s “25 year old” about the approach. All 3-amplifier in-amps work exactly the same and about the only spec difference is in the swing of the output stage. They keep designing new ones, and the only difference is lower power and incrementally better specs. So yeah, sure, you can buy a 2-year-old part instead, but it changes nothing. And in-amps are very flexible parts, so if you got them – use them!

I use my single rail ‘simple current’ inspired by the 1st generation uCurrent – good enough for my hobby stuff!

http://ludzinc.blogspot.com/2015/08/a-simple-plan.html