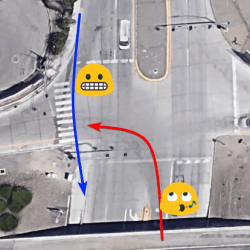

On a dark night in 2006 I was bicycle commuting to my office, oblivious to the countless man made objects orbiting in the sky above me at thousands of miles per hour. My attention was instead focused on a northbound car speeding through a freeway underpass at dozens of miles per hour, oblivious to my southbound headlamp. The car swerved into the left turn lane to get to the freeway on-ramp. The problem? I was only a few feet from crossing the entrance to that very on-ramp! As the car rushed through their left turn I was presented with a split second decision: slow, and possibly stop in the middle of the on-ramp, or just go for it and hope for the best.

By law I had the right of way. But this was no time to start discussing right of way with the driver of the vehicle that threatened to turn me into a dark spot on the road. I followed my gut instinct, and my legs burned in compliance as I sped across that on-ramp entrance with all my might. The oncoming car missed my rear wheel by mere feet! What could have ended in disaster and possibly even death had resulted in a near miss.

Terrestrial vehicles generally have laws and regulations that specify and enforce proper behavior. I had every right to expect the oncoming car be observant of their surroundings or to at least slow to a normal speed before making that turn. In contrast, traffic control in Earth orbit conjures up thoughts of bargain-crazed shoppers packed into a big box store on Black Friday.

So is spacecraft traffic in orbit really a free-for-all? If there were stringent rules, how can they be enforced? Before we explore the answers to those questions, let’s examine the problem we’re here to discuss: stuff in space running into other stuff in space.

What Happens in Orbit Stays in Orbit

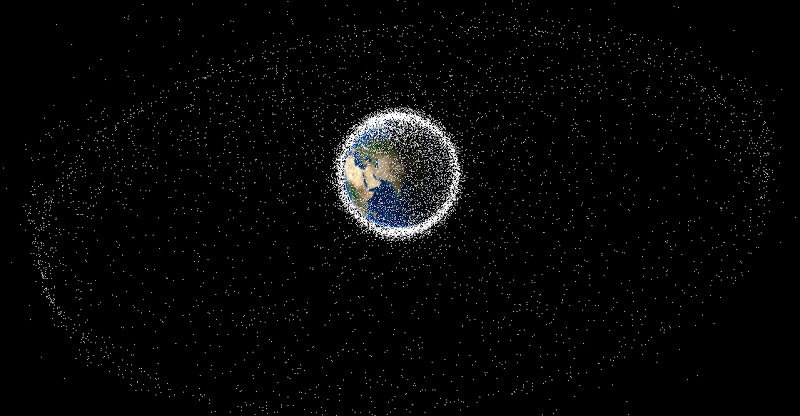

When an object is put into orbit, it does not readily come back to Earth until it is either forced out of orbit with a thruster or until orbital decay allows atmospheric drag to snatch it from the sky. As a result, functional satellites are only a portion of what orbits the Earth. Derelict satellites, debris from broken up spacecraft, and countless other man made objects too small to measure are hurtling above our heads this very moment.

In 2009 Russia’s Cosmos 2251, a decommissioned and uncontrolled satellite at 790 km altitude smashed into the Iridium 33 satellite. Their combined velocity was 42,000 km/h (26,000 mph). Although the Cosmos 2251 was inoperable, it couldn’t have gotten out of the way even if it wanted to — it had no maneuvering abilities even when it was healthy. By 2011, the collision could be held responsible for over 1,000 trackable pieces of debris larger than 10cm. Around this same time, the International Space Station had to maneuver to avoid collisions with some of this debris, with the crew taking shelter inside docked Soyuz capsules just in case. Everything turned out okay.

Of course stray Russian satellites are only the tip of an iceberg. Ascent stages, old satellites, and even debris from the intentional destruction of a satellite in 2007 are all in orbit, ready to collide with whatever gets in their way. Does this mean that Earth orbit is a wasteland of junk, uninhabitable by all but the most heavily armored spacecraft? Not quite.

Close Encounters of the Nerd Kind

When objects in orbit come within one kilometer of each other, it is considered a “close encounter”. One reason for this could be that it is very difficult to track small objects traveling at orbital speeds, and so there must be some room for error. This is especially true in Low Earth Orbit where the distance traveled in each orbit is less than that of a higher orbit. And it is Low Earth Orbit that is the most desirable for a large majority of communications satellite operators, especially those looking for low latency communications such as Starlink and OneWeb.

While Starlink, OneWeb, and other satellite operators have built satellites that can maneuver to avoid collisions, and even remove themselves from orbit, there are other problems that have caused close encounters and near-misses. The first is that many satellites lack any means to navigate, or their operators avoid such maneuvers to save on precious propellant that can’t be refilled.

The second problem is lack of communication and cooperation between satellite operators. In 2019, the ESA satellite Aeolus Earth was forced into a game of space chicken with a Starlink satellite that SpaceX had moved into a conflicting orbit. SpaceX held their ground, causing the ESA to expend precious fuel to thrust their spacecraft out of the way.

Some might point the finger at SpaceX and say that they acted poorly, and that’s a subject for a different article. But did SpaceX break any laws or rules? No.

More Launches, More Junk, More Problems

The discussion thus far has focused on some of the problems that have arisen because of space debris, conflicting orbital paths, and conflicting interests. Is there a solution? Probably.

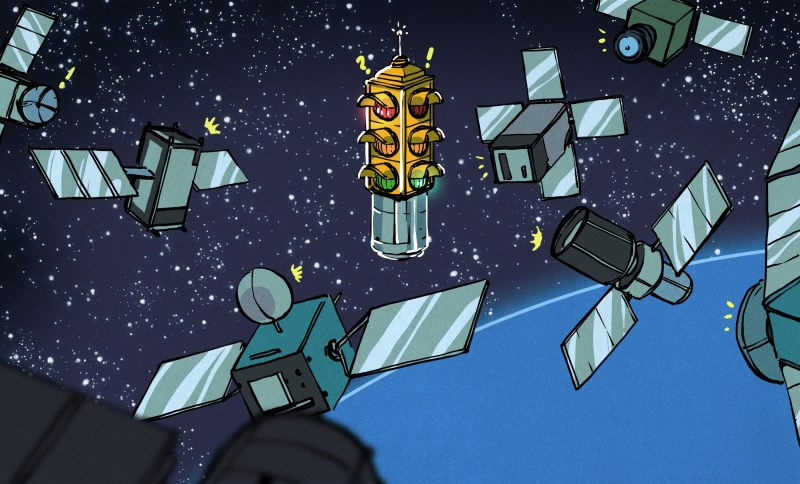

To understand any possible solutions we have to take one more look at the core of the problem: Traffic control. When we think of traffic control, it is easiest to think of traffic that we’re most familiar with: Automobiles, Ships, and Aircraft. Each mode has its own governing entities that have oversight at multiple levels, be it local, regional, state, or national. International treaties and organizations have a say over what is acceptable on a global scale. Cooperation between all makes for relatively safe, controlled travel to and from any cooperating destination. What is at the core of all such traffic control in some way, shape or form? Right of way: The idea that one entity has the right to assert its path at the cost of another.

But once we reach the Kármán line that divides Earth’s atmosphere from outer space, all of that is out the window.

Where There’s a Will There’s a Right of Way

Taming the beast of orbital traffic control has been on the radar of regulators for many years. In 2002 the Inter-Agency Debris Coordination Committee issued a report (PDF) recommending that satellite operators should remove spacecraft and their ascent stages from commonly used orbits no more than 25 years after their missions are complete. Not all have abided by this rule though, and not all even have the ability.

Objects in orbits lower than 600 km will naturally follow the 25 year rule, but those at great altitude will need technology to aid in compliance. Currently there is no incentive to follow the 25 year rule, and there are no legally binding agreements in place to enforce any deterrents. With new operators popping up and incumbents launching dozens of loads a year, the problem continues to grow. What can be done?

A US government funded research firm called The Aerospace Corporation recently published a report on the subject. The report suggested various forms of incentive, ranging from direct government management and mandatory collision insurance to deorbit credits that can be traded like carbon credits.

We also can’t help but wonder if, as object density in various orbits increases, redefining what constitutes a close encounter will help ease fears. Could orbital traffic rules ever catch up to terrestrial law and enforcement, or will operators forever be dodging each other like poorly lit bicycles in the night? Will future space companies start getting demerits on their license for uncooperative behavior? Time will tell. We’d love to hear your thoughts on the subject in the comments below!

“I was bicycle commuting to my office”

How does one become a bicycle? You’re a wizard Harry!

He’s secretly a Transformer.

I think your reading comp skills are a little rusty. He didn’t say “I was a bicycle commuting to my office” which would make him a bicycle. He “was bicycle commuting” or “was […] commuting” via a bicycle. It’s all about syntax. English is an analytic language, you know.

“Call me a taxi!”

“Okay, you’re a taxi!”

Just had the 3rd biker death this year in my county. The county roads out by me only have a narrow gravel shoulder and the roads are full of elevation changes. They all had the right to be on the road, but that isn’t going to help them now…

If I recall correctly, the idea for geosynch sats is that the operator ensure that enough propellant is left at the end of the service life to boost it into a higher “graveyard orbit”

Why not back to earth?

It takes about 100x more delta-v to deorbit a geosync satellite than it does to raise it to a disposal orbit.

Because of ginormuous fuel requirments. Braking so much that you lower your lowest point of your trajectory from 400km to 80km (so you can slam into the atmosphere for free braking) is relatively easy. Doing that from 36Mm to 80km is hard.

Btw. landing on the Moon from any lunar orbit takes roughly as much fuel as getting back to the same orbit.

Having an atmosphere and having it very close in (as in the case of LEO) is a blessing for deorbiting.

No wonder you nearly got hit by the car. You were both traveling on the wrong side of the road ;-)

Which date say would pose the same problem for any space “road” rules. What side are the controls on?

Perfectly normal side for driving if the picture did not get mirrored by somebody :-)

Where do you come from?

At least he was following the “wheels with, feet against” rule.

What I don’t get is when I often see people walking in the street when there’s a perfectly good sidewalk. People even pushing a baby stroller in the street when there’s a perfectly good sidewalk (maybe the street is more flat?).

As a long time bike commuter, you need to adopt the following.

1) Never ever insist on right of way when the other vehicle is a car.

2) After dark, simply assume and act as if you are invisible, because in general, you are to a driver in a car.

Period.

Staying alive and uninjured is all that matters.

3) assume even in daylight, wearing nice vibrant shouty colours you are invisible, as enough drivers treat you as such…

Much as I do love cycling, round here, right now, I’d rather walk much of the time – as the roads and driving standards are frequently approaching terrible.

Part of the problem is, that a cyclist has a silhouette not much bigger than a pedestrian and sometimes it’s speed is difficult to estimate.

Yeah law or not, you’re going to lose to the car…same with riding a motorcycle.

You have to assume that any car is going to do something unpredictable and you’re going to get hurt if you act otherwise.

Absolutely agree! In bicycle-car collisions, even if you are not dead wrong, you will likely be dead right.

For what its worth, I completely agree with you. Even in daylight I rode as if invisible, and it saved me on many occasions. The quoted incident was due partly to the fact that the car was coming at me at a *much* higher speed than expected, and they took the turn at full speed as well. But your points are 100% right on. In fact I had my safety endangered when cars *insisted* on giving me right of way when *other* cars weren’t expecting it.

When I was regularly commuting by bicycle and I was forced to be on the road (the cycle path ended) I found it quite important to behave as a car so that other cars would know what to expect of me. When it came to multi-lane roundabouts I made sure I was in the correct lane and I would sit in the middle of the lane, and indicate correctly, but I’d also go as fast as possible to minimise the frustration to the cars behind me.

Yes, acting as a vehicle rather than a pedestrian is very important! Vehicles need to know where to expect you to be. Taking the lane is an excellent way to do that, and I did so on a regular basis even in the same area where this incident occurred. Because of this article, I’ve been considering it more and I think that had I been in a motor vehicle, the same thing could have happened.

Indeed, while being in the middle of the road and minorly inconveniencing a driver behind can carry risks with road rage arseholes its nearly impossible for them to miss spotting you (or miss you in the other sense), and forcing them to actually give you the space you need is much safer than letting them think they can skim past you when there isn’t the space (and that is assuming they noticed you at all on the side of the road)…

If you are not assertive you will get driven out of the road. Look the river in the eye and make sure he realizes that his nice paint job will get damaged if he doesn’t behave. And then leave yourself enough brake room to avoid looking at the underside of an engine bay.

A loud claxon also helps to get drivers to look up from their phone.

If I were the ESA, I’d probably zap a few dozen SpaceX satellites out of orbit and see if they’re so brave next time around. I’m sure they could find a laser capable of performing the appropriate zapping. That or prohibit everything Musk from being imported to the EU until he pays for the expended fuel and signs some contracts promising to give right of way to already occupied orbital paths. I’m sure their satellite cost more than his, so they were right to move, but never should have needed to. Man that’s irritating.

Please investigate about the consequences of satellite destruction conducted by (wanabe) major space power on debris population and take a read about Kessler’s syndrome (hint: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kessler_syndrome)

You don’t see how having 2 satellites collide would create more junk than burning the antennas off of a few dozen self-deorbiting space wifi routers?

Lasers capable of such things from the ground are rather few and far between – atmospheres get in the way rather a lot… It is also a terrible idea.

You also have to realise that neither side in any such situation want a collision, but equally as there are no rules what each group considers ‘safe’ distance etc can be very different – so the ESA is pissy because SpaceX put something too close to them in their opinion, with some justification, but with no rules how close/ how much risk SpaceX is happy to take is irrelevant – Everybody in space really needs to play nice by a unified traffic rulebook, but till there is one its a free for all where the side that is likely to move their bird often being the one who’s bird costs vastly more so they really don’t want to take any risks with it.

Great article about a tricky subject that we might start to tackle when it’s a bit too late (somehow reminds me of the current massive acceleration of coal power station while the climate is going pretty crazy).

‘Starlink satellites were designed to be able to deorbit on command’: considering a constellation of many thousands of sats, more over with a newspace paradigm (cheap access to space at the expanse on some reliability that can be cut when no human lives are at stakes), how many of these are expected to fail (not even mentioning a catastrophic fail that would lead to in orbit fragmentation) ?

All this only underlines the urge for the international coordination you mentionned…

I think taking current Law of the Sea (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Convention_on_the_Law_of_the_Sea) and Admiralty Law (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Admiralty_law#United_States) as the foundation and adapting it to space could make for a solid and tested foundation to build from. Some examples that are readily applicable:

Navigation:

“More maneuverable vessels must yield to less maneuverable vessels; Smaller vessels must yield to larger vessels.”

According to this rule Cube Sats, Starlink, and the like would need to yield to the larger communications, weather,

and research satellites. Everyone would yield to “Dead” equipment.

Salvage:

If maritime type salvage rules were applied to derelict space craft, it might motivate some agencies to de-orbit their

equipment or spend time in court dealing with salvage claims.

Insurance:

This would further motivate agencies to de-orbit their equipment or spend time in claims court.

There needs to be space flypaper. Put up a satellite that unfurls two giant sheets coated with a super sticky adhesive that won’t dry out or harden due to vacuum and temperature extremes. Tidal forces would naturally orient it radially so that the higher end would sweep up small junk from behind while the lower end would have small junk would smack into it. Once the sticky gets well coated with junk, spin it 180 degrees so the glue on the other side will pick up debris. When that’s full, deorbit it. Keep launching them into different orbits to sweep space clean of small debris that can be dangerous but can’t be tracked.

That sounds to me, like you are suggesting to catch airgun pellets with flypaper. Glue or not, you will end up with holes in the paper.

Perhaps it would be possible to construct a multi-layer structure of fine kevlar fabric, where the objects embed themselves between in the case of an impact, dissipating a part of their kinetic energy in each layer.

Think of a bullet proof vest instead of fly paper. :-)

Easy to tell wherever humans have been. Trash…. ALL OVER!

Let the free market solve the problem. Create a financial incentive to deorbit space junk. This could be a bounty of X per gram deorbited. Finance this by charging a fee for each launch by any corporation, organization or country. If a launch happens with no fee paid, the bounty goes up to 100X for that object insuring it destruction. Payments will be made.

Since Cash is the mother of all inventions, there will be solutions.

Like the free market has handled trading carbon credits? Oh, no, the companies will try to ensure that nothing of the sort ever happens. “It’s cheaper if you just trust us to de-orbit it ” etc.

‘Finance this by charging a fee for each launch by any corporation, organization or country.’ Just like misc. taxes, you can be sure there will be no equivalent to a fiscal paradise…

While the graveyard (GEO + 300km) is a large volume of space it is not a great idea to fill it with junk. There are even fewer controls on what is in there. I would also point out that Starlink is not the only group putting up very large numbers of smallsats. Other US companies, European companies, and Chinese companies have all expressed interest in launching THOUSANDS of smallsats into orbit for various purposes. The truth is that we are already long overdue for a spectacular collision that will create even more debris. Hopefully we will avoid the Kessler Syndrome.