Al Williams wrote up a neat thought piece on why we are so fascinated with robots that come in the shape of people, rather than robots that come in the shape of whatever it is that they’re supposed to be doing. Al is partly convinced that sci-fi is partly responsible, and that it shapes people’s expectations of what robots look like.

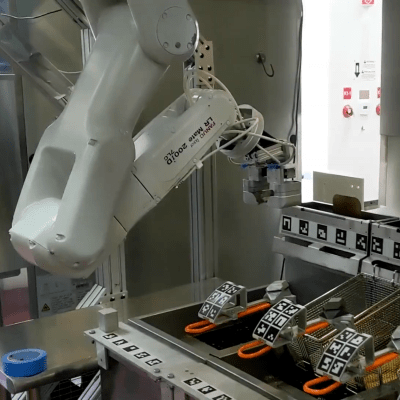

What sparked the whole thought train was the ROAR (robot-on-a-rail) style robot arms that have been popping up, at least in the press, as robot fry cooks. As the name suggests, it’s a robot arm on a rail that moves back and forth across a frying surface and uses CV algorithms to sense and flip burgers. Yes, a burger-flipping robot arm. Al asks why they didn’t just design the flipper into the stovetop, like you would expect with any other assembly line.

What sparked the whole thought train was the ROAR (robot-on-a-rail) style robot arms that have been popping up, at least in the press, as robot fry cooks. As the name suggests, it’s a robot arm on a rail that moves back and forth across a frying surface and uses CV algorithms to sense and flip burgers. Yes, a burger-flipping robot arm. Al asks why they didn’t just design the flipper into the stovetop, like you would expect with any other assembly line.

In this particular case, I think it’s a matter of economics. The burger chains already have an environment that’s designed around human operators flipping the burgers. A robot arm on a rail is simply the cheapest way of automating the task that fits in with the current ergonomics. The robot arm works like a human arm because it has to work in an environment designed for the human arm.

Could you redesign a new automatic burger-flipping system to be more space efficient or more reliable? Probably. If you did, would you end up with a humanoid arm? Not necessarily. But this is about patching robotics into a non-robotic flow, and that means they’re going to have to play by our rules. I’m not going to deny the cool factor of having a robot arm flip burgers, but my guess is that it’s actually the path of least resistance.

It feels kind of strange to think of a sci-fi timeline where the human-looking robots come first, and eventually get replaced by purpose-built intelligent machines that look nothing like us as the environments get entire overhauls, but that may be the way it’s going to play out. Life doesn’t always imitate art.

There is science fiction about a world where humanoid robots were developed first but were later replaced by purpose built robots. Anthony Boucher’s short stories Q.U.R. and Robinc.

https://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/pe.cgi?54028

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/61540/61540-h/61540-h.htm

There is a story by Stanislaw Lem about humanoid robots with advanced AIs entitled “The Washing Machine Tragedy” (available to read at https://archive.org/details/LemStanislawMemoirsOfASpaceTraveller)

Despite being published 4 decades ago, the tale discusses (with a good sense of humor) some matters that we are still to face in a distant future, with sentient machines.

Worth to mention that such tale completely changed my interpretation about the dilemma in Ex-Machina movie.

I’m pretty sure this is just a publicity stunt. A real baking robot is a conveyor belt going through a linear oven.

Yeah. Burger King solved this long ago. Their broilers are pretty space efficient too

Came here to say the same thing. And they would have 2+ such machines for redundancy and fast replacement when necessary.

Not sure I agree that you can get good tasting burgers in one of those pizza oven conveyor belt things.

The goal is good enough, not best. This is cheap fast food.

The way the burger itself is cooked contributes some to flavor, char adds flavor. And a conveyor belt cooker can add a little char – just ask Burger King.

But most flavor comes in after the burger is cooked. A toasted bun plus your choice of toppings makes all the difference in the world.

The advantage is, if the robot fails, a human can easily be dropped in place while the error is remedied, and can function in an efficient, human centric fashion.

They won’t have a staff member trained to do so anyway. Won’t make a difference

Training is minimal, I’m pretty sure.

Put burgers on grill, activate preset timer, flip burger when alarm sounds, remove burger when second alarm sounds. Try not to sneeze on burger.

Here’s your certificate.

You’ve not worked as a short order cook. No-one cooks burgers to a preset timer because there are too many variables involved. Except for McDonalds and Burger King, training is only minimal for someone who already knows how to handle a grill. And these two systems really do use automation.

Well, I think you hit the nail on the head. These robots aren’t short order cooks. They’re burger flippers. They’re operating in a controlled environment, and any wait staff or dishwasher you have on hand should be capable of emulating the simple algorithm it’s tasked with.

I don’t disagree with you. Reduce the job to a simple task and anyone. or anything that can perform a repetitive task can do the job. That’s exactly how McDonald’s system works.

But why bother with a high cost robot flipping burgers on a grill when you can just run them through an Automatic Broiler for a much smaller investment?

https://nieco.com/products/mv2-automatic-broiler/

Now, that is a subjective argument. Some people like greasy, grilled burgers, and some prefer the fat converted to flavor, at the expense of being a little less lubricated. McDonald’s, or Burger King?

It also may be less prone to breaking, but it requires sentient meat machines to operate it.

Two burger machines, working in tandem, solves this problem. One fails, order replacement parts, other machine keeps working until broken machine is fixed.

No flesh bags needed.

Commercial kitchens and work space are sized for the business. There is no space for an extra griddle, robot or ‘flesh bag’.

“I’m not going to deny the cool factor of having a robot arm flip burgers, but my guess is that it’s actually the path of least resistance.”

The programming might be interesting.

One don’t typically associate the term “grease monkey” with programmers!

This has been an install situation in my industry. Our application would’ve made the conventional gantry table seem the cheaper option. But economies of scale and support ultimately lead to a set of fanuc arms.

There’s probably no *single* task where a humanoid design is the best solution. But robot economics are dominated by non-recurring costs, and it is very expensive to design a robot from the ground up every time. If you want to develop a library of design patterns and stock components for general use, then it makes a lot of sense to base that on a humanoid plan, because that can by definition be applied to any human work.

Like the bipedal Boston Dynamics robot. It’s a terribly inefficient design for probably 99% of use cases, but it’s being able to handle those 1% edge cases that make it potentially useful.

Their “handle” robot with the wheels on the ends of legs would be ideal for package delivery. It could take things from an automated delivery truck and carry them over any kind of front yard terrain, up stairs, and set the items down right in front of the recipient’s door.

Years ago I saw a video where a multi jointed robot arm was used with a really long spatula to transfer pastries from one roller conveyor to another. The conveyors came close together at an odd angle and it would’ve cost a lot for a custom built conveyor piece to roll product around that corner, and in the doing of that, the product would end up out of alignment. People had done the job but they can get tired, drop product, get product out of alignment, they need breaks, and they need light.

The robot, fitted with an end of arm attachment to hold the same spatula the human workers used, picked up rows of pastries perfectly every time and placed them onto the other conveyor perfect every time. Never dropped any, could work 24/7 with the lights off.

Also, if the conveyors got reconfigured, the robot could simply be reprogrammed where a custom built device to move the pastries would have to be scrapped.

Or just put them on a conveyer belt like Burger King? That’s probably way easier to automate!

The earliest robotic arm I know of was used in the late 1970’s. We used one at GTE (General Telephone Electronics) Huntsville to reach in and remove trees full of plastic parts from an injection molding machine. The robotic arm worked great for months until one day it didn’t. On that day the arm reached in and didn’t come out, and then the mold closed. It took over a day to peel things apart asses the damage. That day the robotic arm did about 1.5 Million in damage to the mold.

The issue was, some smart Engineers decided that for efficiency we didn’t need the safety interlocks that were required to protect people. And without those interlocks the machines injection cycle timing and the robotic arm timing could run close enough to more than double production from a live operator. This resulted in the mold starting to close as the robotic arm was moving out of the way. And then one day – Oops!