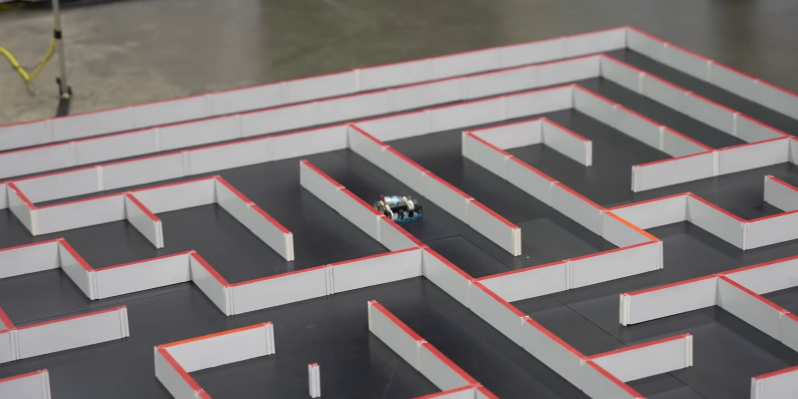

You would think there are only so many ways for a robotic mouse to run a maze, but in its almost 50 year history, competitors in Micromouse events have repeatedly proven this assumption false. In the video after the break, [Veritasium] takes us on a fascinating journey through the development of Micromouse competition robots.

The goal of Micromouse is simple: Get to the destination square (center) of a maze in the shortest time. Competitors are not allowed to update the programming of their vehicles once the layout is revealed at the start of an event. Over the years, there have been several innovations that might seem obvious now but were groundbreaking at the time.

The most obvious first challenge is finding the maze’s center. Simple wall following in the first event in 1977 has developed into variations of the “flood fill” algorithm. Initially, all robots stopped before turning a corner until someone realized that you could cut corners at 45° and move diagonally if the robot is narrow enough. The shortest path is not always the fastest since cornering loses a lot of speed, so it’s sometimes possible to improve time by picking a slightly longer router with fewer corners.

More speed is only good if you can keep control, so many robots now incorporate fans to suck them down, increasing traction. This has led to speeds as high as 7 meters/second and cornering forces of up to 6 G. Even specks of dust can cause loss of control, so all competitors use tape to clean their wheels before a run. Many winning runs are now under 10 seconds, which require many design iterations to increase controllable speed and reduce weight.

All these innovations started as experiments, and the beauty of Microhouse lies in its accessibility. It doesn’t require much of a budget to get started, and the technical barrier to entry is lower than ever. We’ve looked at another Micromouse design before. Even if they aren’t micromice, we can’t get enough of tiny robots.

“You would think there are only so many ways for a robotic mouse to run a maze, but in its almost 50 year history, competitors in Micromouse events have repeatedly proven this assumption false.”

The only thing proven here is that it takes longer than 50 years to run through all the combinations of a maze. The fact that they keep adjusting the maze and that the competition has limited rules allowing for more combinations than anticipated doesn’t mean that the number of ways to run through a maze isn’t limited. The fact that technology progresses and by that affecting the assumed assumption doesn’t help.

Regarding the concept of the contest, this is just so much fun and regarding the video it’s really cool to see the various innovations being presented. As a famous person once said, “It always seems impossible until it’s done”. And quite often when I see something smart I ask myself “why didn’t I think of that?”

I wonder how long it will take before a really smart mouse, equipped with a freaking laser beam shoot’s it’s way through the maze. But I guess there is a rule for that, but if there isn’t one, perhaps there should be one. Otherwise when there are no limits, the number of ways could indeed be limitless and it would be silly to assume that the number of ways is limited.

I was amazed at the almost supernatural speed and manoeuvrability achieved with the downdraft technique. I wondered if that could be applied to full size cars, and – one wikipedia rabbit hole later – why, yes. The world’s fastest car does that. 0-60mph in 1.4 seconds – the McMurtry Speirling – using the same technology!

https://robbreport.com/motors/cars/mcmurtry-speirling-beat-rimac-neveras-acceleration-records-1234787425/

The video of that thing at Goodwood Festival Of Speed is just insane – given the cars that do the run just before it are a billion pound laundry list of the fastest cars in the world & some of the best drivers in the world, this thing makes them all look slow.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5JYp9eGC3Cc

Side-by-side video of it versus the previous record holder, an actual F1 car + driver giving it 100%:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-Q7a0hfp-A

And that is not the only F1 car that’s done it, that’s just the fastest one.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1470449089921787/?hoisted_section_header_type=recently_seen&multi_permalinks=2255470694752952 It was interesting to meet some of the people over the years and very slow to very fast mice and attend one of those competitions.

and being there

https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=duncan%20micromouse

and some software

https://www.facebook.com/search/top?q=duncan%20micromouse

The video was far more interesting than I expected. I almost dismissed it when I saw how long it was, but it was well worth watching.

Isn’t this how the Replicators were conceived?

The next logical step is a MicroDrone competition with 3D mazes :-)

Or have a drone lift off the mouse and show it where to go. If they can use cameras on a lift the next step is tiny drones with cameras.

I’m not so sure what to think about the mice memorizing the maze on the first run and then just running the quickest past on subsequent runs. This makes it much less a maze issue and more a racing issue. It might be more interesting to score based on all runs instead of just the fastest run through the maze.

Without watching the video I wondered how they did it – agree it’s an odd one, two separate problems really.

The maths/software side solving the maze is an interesting intellectual one, but making the thing FAST is a whole other set of engineering challenges.

Problem with a maze is you could have the best algorithm and the best mouse but lose to bad luck. Took a left on your first run instead of a right and didn’t find the end as fast.

The current method seems like a fair compromise. you get 10 minutes to “figure it out” and the video shows that even after decades new techniques were discovered, like working diagonals and calculating not the shortest route, but the fastest based on turns.

I think your misgivings come more from watching what is clearly a matured competition where the winning margin is razor thin. It feels less like the winner is the best programmer but the guy who found a motor with 11% better weight to power ratio or didn’t hit a piece of dust. Nascent competitions with wider margins feel better because you can relate to the excellence of the winner more.

One solution would be to simply up the difficulty (curved walls? variable widths? multiple ends? finding/carrying an object?)to basically slow everyone down again, reset the maturity. Although you don’t want to discourage new people by making it too hard.

Another option might be a weighted score with total maze time. Your fastest “run” is most of your score but you get points for leaving early. trick would be balancing that weight so that luck doesn’t decide the winner.

It is weighted. Total scored time is the time of your best run + (1/30) * total seconds exploring. In addition, as you will see in the video you have 10 real minutes to explore, but your “counted explore time” doesn’t start until you leave the start square. This leads to an interesting balance because speed has gotten so fast, but conversely you could sacrifice weight to lift a camera on a boom and process it for 100% best routing with no counted explore time. In spite of what the video says about flying I saw nothing in the rules (could be an old copy) about launching a camera + wireless module off of your mouse before start. Might be a fun way to skirt the rules for vision without as much weight handicap.

Looks like newer rules are more stringent: https://r1.ieee.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Micromouse-Guideline-2020.pdf