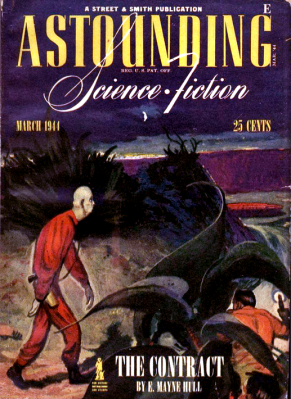

There’s an upcoming movie, Argylle, about an author whose spy novels are a little too accurate, and she becomes a target of a real-life spy game. We haven’t seen the movie, but it made us think of a similar espionage caper from 1944 involving science fiction author Cleve Cartmill. The whole thing played out in the pages of Astounding magazine (now Analog) and involved several other science fiction luminaries ranging from John W. Campbell to Isaac Asimov. It is a great story about how science is — well, science — and no amount of secrecy or legislation can hide it.

In 1943, Cartmill queried Campbell about the possibility of a story that would be known as “Deadline.” It wasn’t his first story, nor would it be his last. But it nearly put him in a Federal prison. Why? The story dealt with an atomic bomb.

Nothing New

By itself, that’s probably not a big deal. H.G. Wells wrote “The World Set Free” in 1914, where he predicted nuclear weapons. But in 1914, it wasn’t clear how that would work exactly. Wells mentioned “uranium and thorium” and wrote a reasonable account of the destructive power:

When he could look down again it was like looking down upon the crater of a small volcano. In the open garden before the Imperial castle a shuddering star of evil splendor spurted and poured up smoke and flame towards them like an accusation. They were too high to distinguish people clearly, or mark the bomb’s effect upon the building until suddenly the facade tottered and crumbled before the flare as sugar dissolves in water.

In fact, other earlier stories also predicted bombs, including 1941’s “Solution Unsatisfactory” by Anson MacDonald, a pseudonym for Robert Heinlen. So why was Carmill’s story of interest to the FBI?

The Story

If you want to read the short story, you can do so thanks to the Internet Archive. Remember, science fiction was simpler then. The major groups in the story are the Sixa and the Seillia. If these don’t mean anything to you, try spelling them backward. Presumably, war-time censors didn’t. We’ll wait.

The two groups are at war, and apparently, both have mastered the atomic bomb. While one side tries to deploy it and fails, the other side refuses, believing it to be amoral. By itself, this is just another story and means no more than Star Trek postulating a photon torpedo.

The description of the bomb and the issues of producing one is what drew attention:

“Have you heard of U-235 ? It’s an isotope of uranium.”

“Who hasn’t?”

“All right. I’m stating fact, not theory. U-235 has been separated in quantity easily sufficient for preliminary atomic-power research, and the like. They got it out of uranium ores by new atomic isotope separation methods; they now have quantities measured in pounds. By ‘they’, I mean Seilla research scientists. But they have not brought the whole amount together, or any major portion of it. Because they are not at all sure that, once started, it would stop before all of it had been consumed — in something like one micromicrosecond of time.”

. . .

“Now the explosion of a pound of U-235,” he said, “wouldn’t be too unbearably violent, though it releases as much energy as a hundred million pounds of TNT. Set off on an island, it might lay waste the whole island, uprooting trees, killing all animal life, but even that fifty thousand tons of TNT wouldn’t seriously disturb the really unimaginable tonnage which even a small island represents.

“The trouble is, they’re afraid that that explosion of energy would be so incomparably violent, its sheer, minute concentration of unbearable energy so great, that surrounding matter would be set off. If you could imagine concentrating half a billion of the most violent lightning strokes you ever saw, compressing all their fury into a space less than half the size of a pack of cigarettes — you’d get some idea of the concentrated essence of hyperviolence that explosion would represent. It’s not simply the amount of energy; it’s the frightful concentration of intensity in a minute volume.

“The surrounding matter, unable to maintain a self-supporting atomic explosion normally, might be hyper-stimulated to atomic explosion under U-235’s forces and, in the immediate neighborhood, release its energy, too. That is, the explosion would not involve only one pound of U-235, but also five or fifty or five thousand tons of other matter. The extent of the explosion is a matter of conjecture.”

The protagonist doing most of the speaking is on a secret mission to destroy the enemy’s bomb, which contains 16 pounds of U-235. He later describes using two hemispheres to separate the reaction mass and neutron shielding when the bomb is inactive.

Apparently, Cartmill’s original idea was just some “super bomb,” but Campbell, who attended MIT and had a physics degree from Duke, passed him background information on atomic bombs gathered from public information.

Los Alamos

Many at Los Alamos read science fiction. In fact, it is rumored that Cambell had noticed a swell in change of address forms to New Mexico and had surmised that something was going on there, although he apparently never mentioned it.

When the story came out in February 1944, workers at Los Alamos started to talk about it. After all, it had concerns very similar to their own. Should the bomb be used? It also identified separation as a major roadblock and the fear that a chain reaction might not stop.

A security officer made note of the conversations and reported it to the FBI. An investigation into Cartmill and Campbell resulted. The FBI even looked into their acquaintances, including Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein.

Investigation and Retrospect

In retrospect, Cartmill’s bomb design probably wouldn’t work, but that might not have been clear in 1944. But it did predict the problem of isotope separation and hinted at several other realistic details.

The amount of effort spent on investigating the story was impressive. The FBI found that Campbell had lunch with an engineer working on an unrelated classified project and interviewed him, too. It didn’t help that Campbell initially claimed all the technical content of the story was due to his influence, while Cartmill claimed he was the architect of the faux nuclear device. Later letters showed that the ideas were, in fact, Campbell’s.

At least one investigator was convinced that some of the story had to be from classified research. However, the FBI never found a link between anyone involved and the Manhattan Project that produced the bomb. In the end, the feds forbade Campbell from running any more stories about uranium or atomic power until after the war.

Yesterday’s science fiction is sometimes tomorrow’s facts. We’ve seen reasonably good approximations of cell phones, self-driving cars, virtual reality, and more. Then again, fiction doesn’t anticipate everything. But just as legislators can’t change the value of pi, keeping science secret is rarely effective for very long. The inquisitive nature of scientists and engineers and the fact that nature keeps no secrets on purpose make it a futile effort.

There was real concern that one nuclear chain reaction could end everything, but that’s not the case or you wouldn’t be reading this. Even today, though, extracting isotopes isn’t child’s play.

Very interesting! Good science fiction is science fact extended to science possibly with an artfull application of scientific imagination.

*possibility

My favorite is “A Logic Named Joe”, published in 1946 that pretty accurately predicts personal computers and the internet. This was before TVs were common.

“You got a logic in your house. It looks like a vision receiver used to, only it’s got keys instead of dials, and you punch the keys for what you wanna get. It’s hooked in to the tank, which has the Carson Circuit all fixed up with relays. Say you punch ‘Station SNAFU’ on your logic. Relays in the tank take over an’ whatever vision-program SNAFU is telecastin’ comes on your screen … But besides that, if you punch for the weather forecast or who won today’s race at Hialeah or who was the mistress of the White House durin’ Garfield’s administration or what is PDQ and R sellin’ for today, that comes on the screen too.”

Also ChatGPT, to an extent…

https://www.uky.edu/~jclark/mas201/Joe.pdf

The “tank” is described as a huge building full of relays that stores all knowledge and can do calculations. A combination of Wikipedia, Amazon Cloud, and Google. Not bad for 1946. And now I want to name a server “tank”.

Expanding on other early works dealing with nuclear weapons there is also Karel Čapek’s(co-inventor of the word robot) 1924 novel Krakatit. But he focuses mostly on the politico-societal aspects of such invention and personal psychology of the inventor rather than the science & engineering of the weapon.

There are stories of similar government/author interactions with Tom Clancy; they tried to put him through a military court marshal b/c of how accurate some of his writing was re: confidential information only to find out he had never been in the military. He was able to make accurate predictions due to publicly accessible data.

Talk about a marketing opportunity, “my stories are so realistic the military tried to court martial me!”

There is a story that when Dr Strangelove came out, the accuracy of the interior of a B-52 Stratofortress (still secret at the time I believe) was so good that there was suspicion that the filmmakers had access to something they shouldn’t have.

Apparently when Kubrik was filming 2001 he was warned not to include some things that NASA advisors had shown him. The Soviets could steal ideas from the USA space program from the movie. Maybe not true, neverless is plausible.

There were also a couple of Superman comics that were banned because they involved atomic energy or atomic weapons:

https://www.cbr.com/superman-atomic-bomb-censored-united-states-government/

Likely because the government didn’t want atomic weapons to seem silly rather than because the comics got too close to reality. And Lex Luthor throwing an atomic hand grenade at Superman is quite silly XD

Not amoral, immoral

Yep, even H.P. Lovecraft mentioned atomic weapons in some stories in the early 1930s. “The Mound” comes to mind, although that was written in 1929, but not published until 1940 (and not in full until the 80s). No specifics on how it would work, of course, but the authors of the time really did think it inevitable that we’d weaponize nuclear technology, and therefore it was reasonable to include it in the arsenal of fictional alien civilizations.

@Al Williams said: “There’s an upcoming movie, Argyle, about an author whose spy novels are a little too accurate, and she becomes a target of a real-life spy game.”

Question Al: Is the upcoming movie called “Argyle” or “Argylle”? I know I’m being pedantic, but I think it’s the latter. See here:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt15009428/

and here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argylle

Premise: Elly Conway, an introverted spy novelist who seldom leaves her home, is drawn into the real world of espionage when the plots of her books get a little too close to the activities of a sinister underground syndicate. When Aiden, an undercover spy, shows up to save her from being kidnapped or killed, Elly and her beloved cat Alfie are plunged into a covert world where nothing, and no one, is what it seems.

Release: In June 2023, it was announced that the film would be released in theaters on February 2, 2024, by Universal Pictures and Apple Original Films, before releasing on Apple TV+ at an undetermined date.

Thanks.

Thanks! Fixed.

There’s also Del Rey’s book “Nerves” which describes a heck of lot, and it even describes how we’d eventually use the nuclear reaction to heat water for power. In fact the significant portion of it happens to be the conclusion that if they aren’t careful the whole plant could explode along the lines of a Trinity et cetera type of explosion. And the book came out about the same time as that maagzine did.

If you start reading the story, you will see that all names in the story are reversed:

Ybor Sebrof => Roby Forbes

Dr. Sitruc => Dr. Curtis

Namreh => Herman (A solder in the Axis ofcourse)

etc.

Two ‘L’s in “Argylle”…. >.<