Having a penchant for cheap second-hand cameras can lead to all manner of interesting equipment. You never know what the next second-hand store will provide, and thus everything from good quality rangefinders an SLRs to handheld snapshot cameras can be yours for what is often a very acceptable price. Most old cameras can use modern film in some way, wither directly or through some manner of adapter, but there is one format that has no modern equivalent and for which refilling a cartridge might be difficult. I’m talking about Kodak’s Disc, the super-compact and convenient snapshot cameras which were their Next Big Thing in the early 1980s. In finding out its history and ultimate fate, I’m surprised to find that it introduced some photographic technologies we all still use today.

Easy Photography For The 1980s

Since their inception, Kodak specialised in easy-to-use consumer cameras and films. While almost all the film formats you can think of were created by the company, their quest was always for a super-convenient product which didn’t require any fiddling about to take photographs. By the 1960s this had given us all-in-one cartridge films and cameras such as the Instamatic series, but their enclosed rolls of conventional film made them bulkier than required. The new camera and film system for the 1980s would replace roll film entirely, replacing it with a disc of film that would be rotated between shots to line up the lens on an new unexposed part of its surface. Thus the film cartridge would be compact and thinner than any other, and the cameras could be smaller, thinner, and lighter too. The Disc format was launched in 1982, and the glossy TV adverts extolled both the svelteness of the cameras and the advanced technology they contained.

The film disc is about 65mm in diameter, with sixteen 10x8mm exposures spaced at every 24 degrees of rotation round its edge. It has a much thicker acetate backing than the more flexible roll film, with a set of sprocket-hole-like cutouts round its edge and a moulded plastic centre boss. The cassette is quite complex, having a protective low friction layer and a vacuum-formed lightproof film window cover and disc advancer inside the two injection moulded halves. Meanwhile the image size is significantly smaller than that of the 16mm 110 cartridge film or a 35mm frame, meaning that Disc films were the first to be released with Kodak’s new higher-resolution tabular grain emulsion. This film had the silver halide crystals aligned flat on the substrate, reducing light scattering.

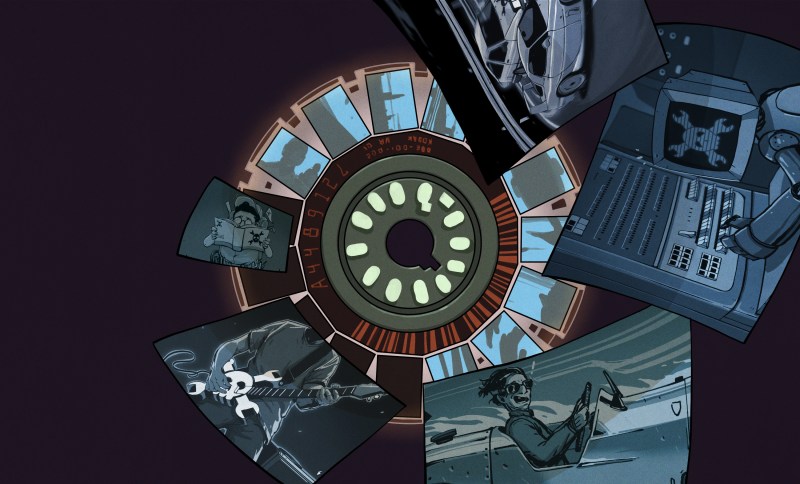

Turning to the camera, for teardown purposes here we have a battered old Kodak 4000. This was the slightly fancier of the disc cameras at launch, but now they can easily be found for pennies in thrift stores. Opening it up is a case of gently easing the aluminum front panel away from the body, revealing all the internals. Once inside the camera, everything is automatic. On the left is the xenon flash tube, the flash capacitor, and a pair of Matsushita lithium batteries, in the middle the circuit board covered by a high voltage warning sticker, and on the right are the mechanical parts. If you teardown one of these for yourself, you’ll want to disconnect the battery as we did, and discharge that flash capacitor. Even four-decade-old lithium batteries can hold enough capacity to charge it, and at 200 volts it packs a punch.

A Lot Of Complexity For A Simple Product

Carefully unsoldering the connections and lifting the board from the camera, we find a mixture of through-hole and surface-mount parts. The flash circuit is conventional, a small single transistor inverter that’s responsible for the “Wheeee” sound you hear when cameras of that era are turned on. The rest of the circuit is interesting, because all the control and light metering circuitry is driven by an integrated circuit. Marked “ACP 152”, it has no makers mark other than stating it was manufactured in Malaysia, and all manner of online searches on the part number reveal nothing. If this camera had been made in 2002 it would certainly be a microcontroller, but in 1982 such a conclusion would be much less likely and would certainly have been central to their marketing if present. Looking at its support components I see no clock circuit or other likely microcontroller ancillaries, so my best guess is it’s an ASIC containing analogue and logic circuitry, forming part of a simple state machine along with the electromechanical cam arrangement in the mechanism.

On the right a small motor turns a wheel (the blue plastic part in the photographs) with that selection of cams that open the window in the film cartridge and cock the shutter, for which the release is electronic via a small electromagnet. One of the functions is to push up a pin which lifts part of the film window cover clear of its locking protrusion, allowing the film to be advanced and the window opened. The lens doesn’t look special but in fact it’s the part which has most relevance to some of the cameras you’ll use today, because it’s the first mass-produced aspherical plastic lens. To deliver as sharp an image as possible on the smaller negative they needed a lens which would minimise aberations, and given the compact size of the camera they couldn’t have a multi-element lens that poked out of the front. This was the solution, and it’s a technology that has had a massive effect on miniature cameras ever since.

Where They Pushed Convenience Too Far

Looking for the first time at the workings of a Disc camera then, it’s a beautiful piece of miniaturisation, but it’s undeniably a complex mechanism when compared to the Instamatic 126 cameras it replaced or the 35mm compact cameras which competed with it. The specialist electronics, the electronic shutter release, and all those mechanical parts are impressive, but there’s a lot in there for a consumer snapshot camera. In doing this teardown we start for the first time to gain an inkling of why the disc format never achieved the success Kodak evidently hoped for it, though it’s when we consider a typical Disc photo that the real reason for its failure emerges.

The Disc’s tiny negative, when combined with the high-resolution film, gave a good quality image. But in those days when photographic prints were the medium through which people consumed their pictures, it was a this smaller negative which led to lower quality enlargements. To solve this problem Kodak sold a complete printing package to laboratories with an enlarger system specifically for Disc film, but many laboratories chose to use their existing equipment instead. The result was that the new cameras often generated disappointing-quality prints. By comparison a 35mm snapshot camera gave a much higher quality and had 36 pictures on a roll of film, so for all its sophistication and innovation the Disc format was not a success. By the 1990s the cameras were gone, and the film followed some time around the millennium. Kodak would try one last shot at ultimate film convenience in the mid 1990s with the Advanced Photo System, but by then the digital camera revolution was well under way.

Looking at the Disc camera here in 2024, it’s clearly a well designed item both mechanically and aesthetically. I have three of them on my bench, they still look sleek, and amazingly those four-decade-old lithium batteries still have enough power to run them. With hindsight it’s easy to say that its shortcomings should have been obvious, but I remember at the time they were seen as futuristic and the way forward. I didn’t buy one though, perhaps it says it all that they were way outside pocket-money prices. Maybe the real insight comes in using Disc to explain why Kodak are now a shadow of their former self; when the reason for extreme convenience in film photography was eclipsed by digital cameras they had nothing else to offer.

I never had a disc camera. My daughter had an APS and I had a 126, but I quickly realised that the cost per image was lower with 35mm, so I went to that, with an Olympus point & shoot. Kodak was all about lock-in and ease of use (for a price). They did however make the first digital camera.

CSB: My former boss was from Rochester and worked on Kodak’s optical storage drives. He worked on the analog control system…and could compute circles around digital me with Laplace transforms.

My first camera was a 110 with telephoto switch. Very small film cartridge but wasn’t good for blowing up photo.

I got APS mid 90s because it was still easier than 35 and did offer better image quality. Then I got hooked on digital camera a few years later.

“The Disc’s tiny negative, when combined with the high-resolution film, gave a good quality image.”

No, they did not. Even a 4×4 print from one of these thumbnail-sized negatives exhibited significant fuzziness from grain effects. Unless fuzz was an intended artistic component of your image, an 8×10 print would be out of the question. I know this because I owned one of those cameras and in fact still have some of the photos I took with it.

Clever design? Yes. Convenient and consumer-friendly? Yes. But “good quality image?” That’s a no.

There are some example photos taken with a Kodak disc camera here:

https://cameralegend.com/2019/01/23/the-worst-cameras-of-all-time-2-the-kodak-disc-camera/

They look rather crummy to me.

“this smaller negative which led to lower quality enlargements. To solve this problem Kodak sold a complete printing package to laboratories with an enlarger system specifically for Disc film, but many laboratories chose to use their existing equipment instead.”

The argument seems to be that the camera itself was capable of quality images but most consumers didn’t get good results because developers weren’t using the bespoke process Kodak offered.

IDK if that’s right but it seems plausible.

This. Most images were as the OP said, not good. Because cheap-ass photo labs skimped on the equipment.

As someone who’s actually worked for money in a film developing lab, “weren’t using the bespoke process” (C-41) doesn’t cut it as an excuse. In general if you “weren’t using the bespoke process” you get terrible results not blurry results. If you didn’t send for instance your Kodachrome to Kansas you got …. black and white negatives, which means black and white prints. Small film size, plastic lenses, what could possibly go wrong? Kodacolor? Fuhgeddaboutit! If you boil a steak, that’s not the butcher’s fault.

They all used C-41. But the article says Kodak sold a special ENLARGER which the labs didn’t want to buy.

So making a crap image BIGGER makes it less crap? Not buying it. Equipment != process. I even included a case where C-41 would be dead wrong.

Kodak lab grade equipment was expensive. I recall working in a film lab operated by 3M Africolor in South Africa circa 1980s we used all Kodak test strips to verify your chemicals daily for quality. However the Disk equipment was relatively expensive. It reqired special developing cassetes and printing attachments for the Kodak manufactured 5S machines.

The qualitybof the print was no match compared to 35mm or 126 which wher the most popular formats it was intended to replace.

Given Kodak’s primary position it is sad it never adapted with the winds of change

Remember 110 film? Like 126 but 13x17mm frame. It gave craptastic images. Disc is a smaller negative than 110.

My sister actually had a 110 SLR camera! Even with good lenses and lots of settings, the tiny negative limited the size of the print.

I went the other way to 120 film. Pain to handle and develop, but great prints that rival even current high megapixel digital cameras. You can still buy it and it’s still awsome (if you’re not into convenience).

Just to help others

110 = 16mm wide stock

120/220 = 61mm

135 = 35mm stock.

135 is indeed 35 mm wide, but sprocket holes cut down the usable width.

A standard image is 24 mm by 36 mm.

Most other still film formats have no holes and use the whole film width.

Most 110s are horrible plastic candybars. Give it an SLR and the quality can be acceptable.

Pentax 110 exists, it’s a 110 format SLR with interchangeable lenses

110 is 16mm film. If it’s poor quality, it’s the lens not the film that’s responsible.

As an example, look at the quality of the videos on this page, shot on Super 8 with about the best possible camera and lens. I’m guessing you wouldn’t expect that quality from 8mm, but there it is.

https://logmar.dk/chatham/

It’s always the lens.

Remember? You can still buy it and get it developed! :)

I worked at Hanimex in Brookvale, Sydney in the film processing lab about 1985/6. I was assigned the job of printing from the disc negatives. The quality was terrible. One night I printed 10,000 discs. It was a terrible job. Kodak made a huge mistake manufacturing the disc camera.

I and my dive buddy both had disc cameras in the 80s but he went a step further by buying an underwater housing for it from Ikelite. I got a housing for my trusty Minolta XGM as well as my Kodak 110 and later my Nikon 8mm video camera. His prints were just okay while of course my 110 and 35mm prints were great. The only convenience of the disc camera was its shirt pocket size and minimal storage of the film in the camera bag. Reprints these days are more expensive than 35mm with some film labs not able to do it as well as my 110s. The cameras are in my Kodak collection that dates back to 1899. Funny that smaller didn’t end up better. The Viewmaster kids toy that predated the Disc camera (the one that gave simulated VR/3D like views) had slightly bigger positives (ie slides) that gave superior images.

That’s a different Garth, not me, Garth Wilson. I had a prof in college who took slides in the field with a 110 SLR and showed them in class with a small slide projector. The quality wasn’t as good as 35mm of course, nevertheless, surprisingly good.

I briefly used a disc camera in the late ’80s. I remember it being kind of clumsy to use. It wasn’t very compact. But it was shiny, new, and different for the sake of being shiny, new, and different.

My previous camera was an Instamatic 300 from the ’60s that I inherited from my grandfather. It was blocky (though still smaller than an SLR), distinctly low-tech, but it was dead simple to use and took pretty good pictures. This was as fancy-pants as low-end film cameras ever needed to be.

my grandma had one of those back in the 80’s

that is all

I bought one for my Mom when they came out. It got used once or twice, but the quality was no different than my plastic Bazooka Bubble Gum camera. It was worse than 126 and 110 film of the day. It got thrown in the drawer never to be used again. I liked 35mm and advantix the best. I never got into photography…..just wanted some memories that looked better than coloured sand.

The same could be said of 110.

The year before (1981), Sony prototyped the Mavica, which was a video-still-format camera that recorded to an analog floppy disk.

I have an original in my collection.

I have two of them, one was given to me by the librarian in the school I work in.

Used them when I went to Maine to visit family one winter, took decent photos for a floppy drive system that was 15 years old at the time.

My brother took pictures at my son’s wedding 25 years ago, and they are not so good, but they were recorded on a digital 3.5 inch disk.

“The film disc is about 65mm in diameter, with sixteen 10x8mm exposures spaced at every 24 degrees of rotation round its edge.”

The example negative clearly has 15 exposures not 16. They’re even numbered.

To get 16 exposures 24 degrees apart you have to use the special 384 degree circular film disc (sold separately).

In fact, the fact that it held an odd number of exposures was a major criticism at the time it was introduced. An even number could have lent itself to a stereo camera, with discs similar to the Viewmaster.

Correctamundo. 24×16=?

“Answer after the break”

I had a completely mechanical disc camera made by a company called Ansco when I was a kid. Worst film photos ever. It wasn’t until I started seeing the results coming from some of the early digital cameras that I saw worse results.

As a side note, I went on a tour of the Rochester, NY Kodak plant when I was a kid, right around the time that they were getting themselves all hyped up for the “new” disc camera. Interesting tour, terrible film format.

In the U.S. in the 1960s, Ansco (later GAF) based in Binghamton, N.Y. was the biggest competitor to Kodak. Ansco produced the first ASA 500 color slide film. My impression was that Ansco management was not as dedicated to photography as Kodak management, and that was reflected in films that weren’t quite as good.

Our family got one in the mid 80s, only used a few reloads as I recall. A snappy ad campaign sold it to my mother, “Look out brother look out sis I’m gonna get you with the Kodak disk!” My father had a rarely used Canon 35mm which I am not sure I was ever allowed to touch.

I ended up having fun with a cheap 110 ‘spy’ camera reminiscent of a cheapest knockoff of a Minox. I shot quite a few rolls of that 110 in the late 80s and carried it and a few rolls of 200 and 400 speed color with me most everywhere. Terrible pinhole photography but 110 was a cheap smart simple ultra portable format, the disc was a wierd choice for a gimmick; why not get a 35mm cheapie camera which at least had a chance of a good picture or a portable 110?

For my sins I worked at that time in one of London’s largest and most famous camera stores – we counted royalty amongst our customers. The arrival of the disk camera was.a bit too far. While I imagine Kodak thought that their customers could be served with less quality than before, the fact was the quality was rubbish irrespective of which camera you had or processor developed the film. Almost everyone could see that for whatever combinations of reasons the prints were.lousy. I’m not quite sure where to place the blame. Minox negatives were probably about the same size and there were cracking, if grainy prints made from them. Most subminiature cameras produced reasonable results. in the end I think it was a combination of camera and processing comprises, unlike say, Minox, which was hand processed.

I have a disk film Kodak slide projector I’m about to throw away.

I have a 1980s vintage mass spec that I’m about to throw away.

I inherited it from my dad, he was about to throw it away for 20 years.

The the day after it’s gone, I’ll need a good strong magnet, vacuum pump etc.

I may actually tackle to computer someday. Vintage IBM lab computer thingy.

I’ll get to it, right after the prerelease Amiga and 64.5 mustang.

Forrest Mims did an article (Radio Electronics?) where he “hacked the camera” by adding an electronic switch and used it to take aerial photos.

Someone could have also added a pole and created the first selfie stick! I had one and never through of that, though I considered make a wildlife camera with the one I had.

I worked at Kodak in Harrow. Kodak were notorious at making statements that would come back and bite them in the ass. I remember one “State of the nation” talk we had when the top honcho came over from Rochester to talk to us. He said silver halide was strong and would sell for years, it had a fantastic future and that digital photography would never take off. He said our jobs were safe. One week later Fuji had a digital camera and printer released that changed the way photography would go. Kodak tried to hit back with its DCS cameras but the horse had already bolted. 6 months later we were all made redundant. Kodak have always been slow off the start, ignorant in many ways some may say they had their head in the sand.

I’d never thought about disk film much – I assumed it was the same idea as 110, but even less appealing. I’m still unclear if disk cameras actually were smaller in any useful sense, but it’s interesting to learn that the film itself was supposed to be technically improved.

It makes you wonder, in an alternate timeline, how they would’ve adapted this for a 35mm replacement (assuming the rigid film is critical). Maybe a sort of matchbox with 36 little rigid plates inside?

Internationally there was plenty of competition in the film industry. There was relentless effort to produce finer grained and faster films, and films with truer and more stable colors. I particularly remember 2 improvements in B&W film. Fujifilm came out with a dye-coupled B&W negative film that was processed as a color negative film. Since color negative processing removes the silver and the dye tends to spread a bit, the result is smoother. Kodak developed films with a tabular grain structure (T-Max films), which improved the speed/graininess tradeoff.

One picture more on the film and somebody could have built a stereo camera. I had to build my own using normal 36mm film

36mm? That’s going the long way round, Shirley? Do they even still make that? Apparently the 11th Commandment around here is “Thou shalt not allow edits.”

In the mid 80’s I worked summer jobs in a camera store when the Disk cameras came out. I hated selling them knowing that the image quality was just terrible and would try to steer customers away from them. Some just wanted the latest thing for snapshots and didn’t really care about the quality. At least we sent the film back to a Kodak lab for processing so got the most out of it. Sad how Kodak really had their heads buried in the sand when it came to digital, despite them having many patents in the technology.

I worked at a camera store in the early 80 s, unless a customer came in, and especifically asked for the disc camera we made no effort to sell one. The image quality was terrible as compared to the Canon Sureshot, which owned the point, and shoot market at the time.

Most disc camera owners were highly dissatisfied with their camera, and far too many came back, and yelled at us for selling them one demanding their money back.

I found several old Kodak disks in a trunk. They are all on the 15x mark. Does that mean they are new or that there would be pictures on it? Did that disk count down or count up?