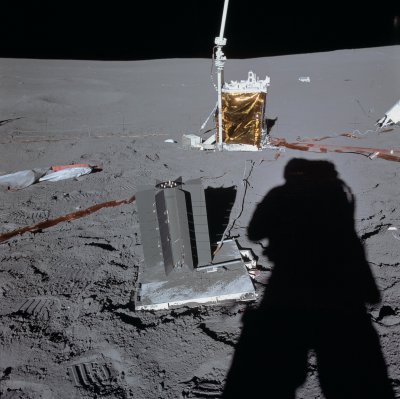

Although the US’ Moon landings were mostly made famous by the fact that it featured real-life human beings bunny hopping across the lunar surface, they weren’t there just for a refreshing stroll over the lunar regolith in deep vacuum. Starting with an early experimental kit (EASEP) that was part of the Apollo 11 mission, the Apollo 12 through Apollo 17 were provided with the full ALSEP (Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package). It’s this latter which is the subject of a video by [Our Own Devices].

Despite the Apollo missions featuring only one actual scientist (Harrison Schmitt, geologist), these Bendix-manufactured ALSEPs were modular, portable laboratories for running experiments on the moon, with each experiment carefully prepared by scientists back on Earth. Powered by a SNAP-27 radioisotope generator (RTG), each ALSEP also featured the same Central Station command module and transceiver. Each Apollo mission starting with 12 carried a new set of experimental modules which the astronauts would set up once on the lunar surface, following the deployment procedure for that particular set of modules.

Although the connection with the ALSEPs was terminated after the funding for the Apollo project was ended by US Congress, their transceivers remained active until they ran out of power, but not before they provided years worth of scientific data on many aspects on the Moon, including its subsurface characteristics and exposure to charged particles from the Sun. These would provide most of our knowledge of our Moon until the recent string of lunar landings by robotic explorers.

Heading image: Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package of the Apollo 16 mission (Credit: NASA)

Not a hack…

Humans in space is definitely a hack. Why wouldn’t you want to know about the cool stuff they did there?

Once again, the hack is in the comments

Want something to hack, on the moon?, the dust!

Looking at the pictures shows how the dust was one of the biggest issues, fantasticly fine, statickly charged, adrasive, and everywhere in unlimited quantities.The dust is also I believe chemicaly reactive with

water and likely other things bieng brought to the moon.

The dust is bad enough that any long term outpost on the moon will

need some way to keep habitation and any presurised work areas dust free, and sealing locks and moving parts will be difficult.

Mars is different, as there is enough water , atmosphere and gravity to cement a lot of the dust, still a problem, but the moon dust is a huge challenge.

Robots don’t mind the dust.

The Mars insight probe disagrees

https://edition.cnn.com/2022/05/17/world/nasa-mars-insight-lander-update-scn/index.html

There has been some thought on using solar or nuclear to crack the aluminum and oxygen apart in regolith, then recombine them violently as solid fuel boosters. Not the best rocket in the universe, but considering it’s basically free while you’re on the moon… It’s good enough to get a lot of other useful stuff out of the gravity well:

https://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/enginelist.php#id–Chemical–Hybrid_Rocket–Aluminum-Oxygen

“In space, energy is cheap, matter is expensive.” –Decent rule of thumb

Ok, here’s the ‘hack’ angle…. could alsep been fixed on Apollo 16

On Apollo 16 the holes for the probes were dug by Charles Duke who managed to drill down to 3 m (10 ft) below the surface.[4] The drill on Apollo 16 had been modified to rectify the issues experienced on the prior mission, Apollo 15. The experiment came to an end before it started when John Young tripped over the cable connecting the experiment to the ALSEP central station.[5][4] The cabling was designed to resist tensile strains from being tugged, but it was not designed to resist tearing motions.[1] Repairing was considered but rejected due to it needing several hours of surface time.[4]

from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heat_Flow_Experiment

“Shucks… Could someone duck out to the convenience store for a spare USB cable??”

Oh, yes, there were hacks.

Inside stories from a Bendix ALSEP engineer: https://aadl.org/catalog/record/accidental-engineer-a-sixty-year-trek-through-technology-and-beyond

The moon stories start around page 35. Funny bit about the failed Lunar Surface Gravimeter is in the next chapter, around page 52.

I never thought about this before, but Apollo 13 would have carried one of these.

Unfortunately, ’13 didn’t make it to the moon. Instead it skipped the lunar orbit injection burn and the entire stack returned to the earth, with the attached lander acting as a lifeboat of sorts.

I always assumed that the lander was just jettisoned at the last minute and burned up in the atmosphere.

So… where’s the RTG with all that plutonium 240?

The failure of the Apollo 13 mission in April 1970 meant that the Lunar Module reentered the atmosphere carrying an RTG and burned up over Fiji. It carried a SNAP-27 RTG containing 44,500 Ci (1,650 TBq) of plutonium dioxide in a graphite cask on the lander leg which survived reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere intact, as it was designed to do, the trajectory being arranged so that it would plunge into 6–9 kilometers of water in the Tonga trench in the Pacific Ocean. The absence of plutonium-238 contamination in atmospheric and seawater sampling confirmed the assumption that the cask is intact on the seabed. The cask is expected to contain the fuel for at least 10 half-lives (870 years). The US Department of Energy has conducted seawater tests and determined that the graphite casing, which was designed to withstand reentry, is stable and no release of plutonium should occur. Subsequent investigations have found no increase in the natural background radiation in the area. The Apollo 13 accident represents an extreme scenario because of the high re-entry velocities of the craft returning from cis-lunar space (the region between Earth’s atmosphere and the Moon). This accident has served to validate the design of later-generation RTGs as highly safe.

from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Radioisotope_thermoelectric_generator

It’s quick to ask a question, but posting a comprehensive answer with a supporting link takes time. Thank you for taking the time to do so, I really mean it. This is why I read Hackaday and not “social media.”

The Active Seismic Experiment component of ALSEP (Apollo 14 and 16) left behind a set of 5 unused seismic grenades. I hope that this info becomes useful one day, either for an Apollo 13 style hack of the future, or as part of the plot in some cool fiction.