Humans have been chemically modifying their world for far longer than you might think. Long before they had the slightest idea of what was happening chemically, they were turning clay into bricks, making cement from limestone, and figuring out how to mix metals in just the right proportions to make useful new alloys like bronze. The chemical principles behind all this could wait; there was a world to build, after all.

Among these early feats of chemical happenstance was the discovery that glass could be made from simple sand. The earliest glass, likely accidentally created by a big fire on a sandy surface, probably wasn’t good for much besides decorations. It wouldn’t have taken long to realize that this stuff was fantastically useful, both as a building material and a tool, and that a pinch of this and a little of that could greatly affect its properties. The chemistry of glass has been finely tuned since those early experiments, and the process has been scaled up to incredible proportions, enough to make glass production one of the largest chemical industries in the world today.

Sand++

When most of us use the word “glass,” we’ve got a pretty clear mental picture of what the term refers to. But from a solid-state chemistry viewpoint, glass means more than the stuff that fills the holes in your walls or makes up that beer bottle in your hand. Glasses, or more correctly glassy solids, are a class of amorphous solids that undergo a glass transition. Unpacking that, amorphous refers to the internal structure of the material, which lacks the long-range structural regularity characteristic of a crystalline solid. Long range in this context is a relative term, and refers to distances of more than a few nanometers.

As for the glass transition bit, that simply refers to the material changing from a brittle, hard solid state to a viscous liquid as it is heated past its glass transition temperature. Coupled together, these properties mean that many materials can be glassy solids, including plastics and metals. For our purposes, though, glass refers to glassy solids made primarily of silicates, with other materials added to change the properties of the finished material.

To understand the amorphous structure of glass, we need to look at the starting material for manufacturing glass: quartz. Quartz is a crystalline solid made from silicon dioxide (SiO2), or silica. Inside the crystal, each silicon atom is bonded to four oxygen atoms, each of which forms a bridge to a neighboring silicon. This results in a tetrahedral unit cell, giving both natural and synthetic quartz many of their useful properties.

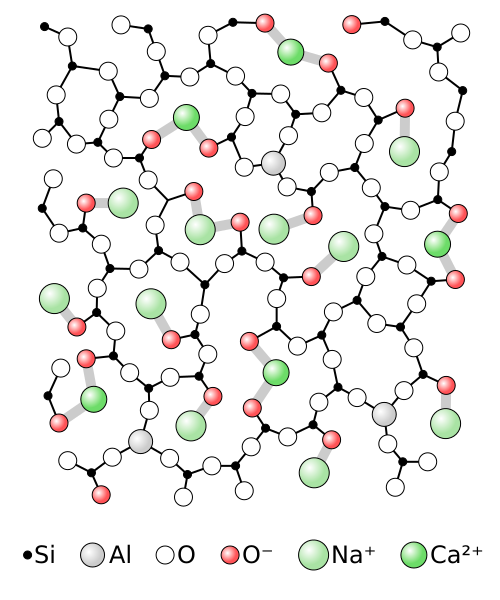

When quartz sand is ground up finely and heated above its melting point of 1,700C, the rigidly ordered crystal structure is disrupted and a thick, syrupy liquid forms. Cooling that liquid slowly would allow the crystal structure to reform, with the silicon atoms connected by a regular grid of bridging oxygen atoms. Glass production, though, uses faster cooling, which makes it harder for all the oxygen atoms to form bridges between the silicon atoms. The result is a disrupted pattern, with some silicon atoms bonded to four oxygens and some bonded to only two or three. This disrupts the long-range ordering seen in the original quartz crystals and results in the properties we normally associate with glassy solids, such as brittleness, low electrical conductivity, and a high melting temperature.

Glass made from pure silica sand is called fused quartz, and while it’s commercially valuable, especially in situations requiring extreme temperature resistance and transparency over a wide range of the optical spectrum, it also has some drawbacks. First, the extreme temperatures needed to melt pure quartz sand require a lot of energy, making fused quartz expensive to produce in bulk. Also, the liquid glass is extremely viscous, making it difficult.

Luckily, these properties can be altered by adding a few impurities to the melt. Adding about 13% sodium oxide (Na2O), 10% calcium oxide (CaO), and a percent or so of aluminum oxide (Al2O3) dramatically changes the physical and chemical properties of the mix. The sodium oxide generally comes from sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), which is known as soda, and the calcium carbonate comes from lime, which is limestone that has been heated. Together, the sodium and the calcium bind to some of the oxygen atoms in the silicates, blocking them from bridging to other silicates. This further disrupts any long-range interactions, lowering the melting point of the mix and decreasing its viscosity. The result is soda-lime glass, which accounts for about 90% of the 130 million tonnes of glass manufactured each year.

If You Can’t Stand the Heat…

Soda-lime glass is used for everything from food and beverage containers to window glass, with only slight adjustments to the mix of impurities to match the properties of the finished glass to the job. But if there’s one place where plain soda-lime glass falls short, it’s resistance to thermal shock. Thanks to the disruption of long-range interactions between silicates by sodium and calcium, soda-lime glass has a much higher coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) than fused silica. This makes heating soda-lime glass risky, since the stress caused by expansion or contraction can cause the glass to shatter.

To lower the CTE of soda-lime glass, a small amount of boron trioxide (BO3) is added to the melt. The boron atoms bind to two oxygen atoms, which forms a bridge between adjacent silicates, albeit slightly longer than an oxygen-only bridge. This would seem to raise the CTE, but boron has another trick up its sleeve. Boron normally only accepts three bonds, but in the presence of alkali metals like sodium, it will accept one more. That means the sodium atoms will bond to the boron, keeping them from blocking more bridging oxygens. The result is borosilicate glass, which has a viscosity low enough to ease manufacturing and a low CTE to withstand thermal shock.

Borosilicate glass has been around for more than a century, most recognizably under the trade name Pyrex. It quickly became a fixture in kitchens around the world as the miracle cookware that could go from refrigerator to oven without shattering. Sadly, Corning no longer sells borosilicate glass cookware in the North American market, opting to sell tempered soda-lime glassware under the Pyrex brand since about 1998. True borosilicate Pyrex glass is most limited to the laboratory and industrial market now, although Pyrex cookware is still available in Europe.

The Glassworks

In a way, glass is a bit like electricity, which is largely consumed the instant it’s produced since there aren’t many practical ways to store it at a grid scale. Similarly, glass really can’t be manufactured and stored in bulk the way other materials like aluminum and steel can, and shipping tankers of molten glass from one factory to another is a practical impossibility. So a glasswork generally has a complete manufacturing process under one roof, with raw materials coming in one end and finished products going out the other. This also makes glassworks very large facilities, especially ones that make float glass.

Another way in which glass manufacturing is similar to electric generation is that both are generally continuous processes. Large base load generators are most efficient when they are kept rotating continuously, and spinning them up from a standing start is a long and tedious process. Similarly, glass furnaces, which are often classified by the number of metric tons of melt they can supply per day, can take days or weeks to get up to working temperature. That means the entire glass factory has to be geared around keeping the furnace fed with raw material and ensuring the output is formed into finished products immediately and continuously.

On the supply side of the glassworks is the batch house, which serves as a warehouse for raw material. Sand, soda, lime, and other bulk ingredients arrive by truck or rail and are stored in silos or piled onto the batch house floor. It’s vitally important that the raw ingredients stay clean and dry; the results of a wet mix being dumped into a furnace full of 1,500° molten glass don’t bear thinking. An important raw material is cullet, which is broken glass either from recycling or from the production process; adding cullet to the mix reduces the energy needed to melt the batch. Ingredients are weighed and mixed in the batch house and transported by conveyors to the dog house, an area directly adjacent to the inlet of the furnace where the mix is prewarmed to remove any remaining moisture before being pushed into the furnace by a pusher arm.

The furnace is made from refractory bricks and usually has a long and broad but fairly shallow pool covered by an arched roof. Most furnaces are heated with natural gas, although some electric arc furnaces are used. The furnace often has two zones, the melting tank and the working tank, which are separated by a wall with narrow openings. The temperatures of the two chambers are maintained at different levels, with the melting tank generally hotter than the working tank. The working tank also sometimes has chlorine gas bubbled through it to consolidate any impurities into a slag that floats to the surface of the melt, where it can be skimmed off and added to the cullet in the batch house.

Float, Blow, Press, Repeat

After the furnace, the liquid glass enters the cold end of the glassworks. This is a relative term, of course, since the glass is still incandescent at this point. How it exits the furnace and is formed depends on the finished product. For sheet glass such as architectural glass, the float process is generally used. Liquid glass exiting the furnace is floated on top of a pool of molten tin, which is denser than the glass. The liquid glass spreads out over the surface of the tin, forming wide sheets of perfectly flat glass. The thickness and width of the sheet can be controlled by rollers at the edge of the tin pool, which grab the glass sheet and pull it along.

Float baths can be up to four meters wide and 50 meters or more long, over which length the temperature is gradually reduced from about 1,100° to 600°. At that point, the glass rolls off the tin bath onto rollers and enters a long annealing oven called a lehr, which drops the temperature over 100 meters or more before the sheets are cut. The edges, which were dimpled by the rollers in the float bath, are cut off by scoring with diamond wheels and snapping with rollers, with the off-cuts added to the cullet in the batch house. The glass ribbon is cut to length by a scoring wheel set at an angle matched to the speed of the conveyor to make straight scores across the sheet and snapped by a conveyor belt that raises up at just the right time to snap the sheet.

Float glass often goes through additional post-processing modifications, such as tempering. While it’s still quite hot, float glass can be rapidly cooled with jets of air from above and below. This creates thin layers on both faces that have solidified while the core of the sheet is still fluid, putting the faces into tension relative to the core, which is in compression. This dramatically toughens the glass compared to plain annealed glass, and when it does break, the opposed forces within the glass force it to shatter into small fragments rather than large shards.

For hollow glass products, the arrangement of the cold end forming machines is a bit different. Rather than flowing horizontally out of the furnace, melted glass drops through holes in the bottom of the tank. Large shears close at intervals to cut the stream of molten glass into precisely sized pieces called gobs, which drop into curved chutes. The chutes rotate to direct the gobs into an automatic molding machine.

Molding something like a bottle is a multistage process, with gobs first formed into a rough hollow shape called a parison. The parison can be formed either by pressing the gob into an upside-down mold with a plunger to form a cavity, or by blowing compressed air into the mold from below. Either way, the parisons are flipped rightside-up by the molding machine and moved to a second mold, where the final shape of the bottle is formed by compressed air before being pushed onto a conveyor that takes the bottles to an annealing lehr. The entire process from furnace to formed bottle only takes a few seconds, and never stops.

Some glass hollowware products, such as pie plates, baking dishes, and laboratory beakers, do not need to be blown at all. Rather, these are press molded by dropping gob directly into one half of a mold and pressing it with a matching mold. The mold halves squeeze the molten glass into its final shape before the mold opens and the formed item is whisked away for annealing

No matter what the final form of the glass being produced, the degree of coordination required to keep a glass factory running smoothly is pretty amazing. The speed with which ingredients are added to the furnace has to match the speed of finished products being taken off the line at the end, and temperatures have to be rigidly controlled all along the way. Also, all the machinery has to be engineered to withstand lava-like temperatures without breaking down; imagine the mess that would result if a furnace broke down with a couple of tonnes of molten glass in it. Also, molding machines have to deal with the fact that molds only last a few shifts before they need to be resurfaced, lest imperfections creep into the finished products. This means taking individual molding stations out of service while the rest stay in production, all while maintaining overall throughput.

The history of flat glassmaking is interesting in itself. Originating from the Indus valley area, through to trade it became known in the Levant and later the Greek and Roman empires, but in the 16th century it was mainly produced in Benin and Venice, the latter of which was known for it’s exceptionally clear glass.

This process was kept secret. The French (where mirrors were very much in vogue) persuaded some Venitians to work with them. They became too distracted by everything Paris had to offer (and wood for the furnaces was very expensive) so the French state moved them to Normandy, to eventually form the company Saint Gobain.

Some of the venitians fled to Belgium, where they created a glassmaking hotspot around Charleroi. In the 19th century, a group of Belgian glassmakers moved to Pennsylvania, founding the city of Charleroi (now a suburb of Pittsburgh) and made glass there – the eventual successors now being PPG Industries (formerly Pittsburg Plate Glass).

The Belgians were the first to be able to create tube (or cylinder) glass – blowing huge bottles of glass, then cutting the ends off, opening them along a line and then unfolding them flat – the first practical means to make more or less flat glass before the float glass process was invented.

This is very interesting history. Thank you for bringing it to this article as it adds value to what is already written.

Bit on glass history that blew my mind most was the scale and organisation of production during the Roman Empire – seems they made huge slabs of glass in modern day Egypt (maybe other places around that region) if memory serves as the raw materials where there and would ship these several ton blocks around to be reworked to end products. Saw a picture once of one of these slabs with size context and it was so crazy it really stuck with me, the darn thing was bigger than you’d think remotely practical to ship even today, but obviously they where managing it.

Presumably there will be a few of these at the bottom of the Med then?

I’d expect so, after all no boats being lost in who knows how many years (quite possibly more than a century) seems unlikely. But the one I’ve seen IIRC was found on the banks of the river, and looked like a really really giant slab of concrete with all the surface scouring and dust coating, so presumably it was awaiting loading.

Just found this via a Facebook link: https://news.mit.edu/2015/3-d-printing-transparent-glass-0914

Great article! I’ve always found glass to be fascinating, both because I went into chemistry and because I used to grind, polish, and figure telescope mirrors. Took the family to Seattle for a vacation a long while back, and spent most of a day at a glassblowing facility. Each of us supervised the preparation of a custom glass vase or dish. Loads of fun!

Most of you reading this probably know already that most–NOT all–glassware labeled as PYREX is borosilicate (yellowish), while lowercase pyrex is tempered soda-lime glass (blue-green). I still have a number of PYREX kitchen items which I’m quite careful with; if it breaks I doubt that I’ll ever be able to find one at the flea markets.

Finally, a fun fact: manganese compounds are added to some types of glass to make them colorless rather than blue-green. Left in the sun for a long time, UV slowly converts the +2 and +4 manganese ions to the purple +7 state. Which is why you see purple glass items left in desert sun.

I do some art glassblowing and I find the weird metal oxide colorants really interesting: how a lot of them change to some entirely different color when hot, and some then end up a third color when they cool back down. White glass (of the type I use) turns transparent when it gets hot and is hard to see accurately. Glass with dissolved gold chloride is a really spectacular red once it’s been through a hot/cold cycle.

Great article!

Great article! One correction… in any glass tempering process (there are several methods) the surface is put into COMPRESSION, while the core is put into TENSION. Doing the opposite (as you said) would allow surface tension to break the glass at any of the numerous imperfections that occur in (or are caused in) the surface of the glass.

I was going to post the same comment!

Other variants of this are like what’s used in Gorilla Glass (ion exchange) and also Corelle’s method – a 3-layer glass laminate, with middle layer shrinking slightly more than the outer ones. In each case, external surfaces are in very high compression, resulting in much more durable glass.

Sodium carbonate has a couple of interesting historical associations. The first industrial process to create it was the Leblanc process, which you can read about on the Wikipedia. This used sodium chloride (sea salt) and disposed of the unwanted chlorine in the form of GASEOUS CONCENTRATED HYDROCHLORIC ACID. They also produced calcium sulphide, which was dumped left to weather, which produced hydrogen sulphide. As a result you didn’t to live downwind from a Leblanc plant. An 1839 lawsuit against one alleged “the gas from these manufactories is of such a deleterious nature as to blight everything within its influence, and is alike baneful to health and property. The herbage of the fields in their vicinity is scorched, the gardens neither yield fruit nor vegetables; many flourishing trees have lately become rotten naked sticks. Cattle and poultry droop and pine away. It tarnishes the furniture in our houses, and when we are exposed to it, which is of frequent occurrence, we are afflicted with coughs and pains in the head … all of which we attribute to the Alkali works.” In 1863 Britain passed an Alkali Act to prevent the discharge of gaseous hydrogen chloride from Leblanc plants – the first modern air pollution legislation.

The Leblanc process was eventually superseded by the Solvay process. Ernest Solvay earned a huge amount of money from this and invested some of it in creating the International Solvay Institutes for Physics and Chemistry. Several Solvay Conferences held by these institutes addressed major issues of the time and the 1927 one has become legendary as it was attended by, among others, Bohr, Born, de Broglie, Curie, Dirac, Einstein, Heisenberg, Pauli, and Schrödinger.