When you think of printing on paper, you probably think of an ink jet or a laser printer. If you happen to think of a thermal printer, we bet you think of something like a receipt printer: fast and monochrome. But in the last few decades, there’s been a family of niche printers designed to print snapshots in color using thermal technology. Some of them are built into cameras and some are about the size of a chunky cell phone battery, but they all rely on a Polaroid-developed technology for doing high-definition color printing known as Zink — a portmanteau of zero ink.

For whatever reason, these printers aren’t a household name even though they’ve been around for a while. Yet, someone must be using them. You can buy printers and paper quite readily and relatively inexpensively. Recently, I saw an HP-branded Zink printer in action, and I wasn’t expecting much. But I was stunned at the picture quality. Sure, it can’t print a very large photo, but for little wallet-size snaps, it did a great job.

The Tech

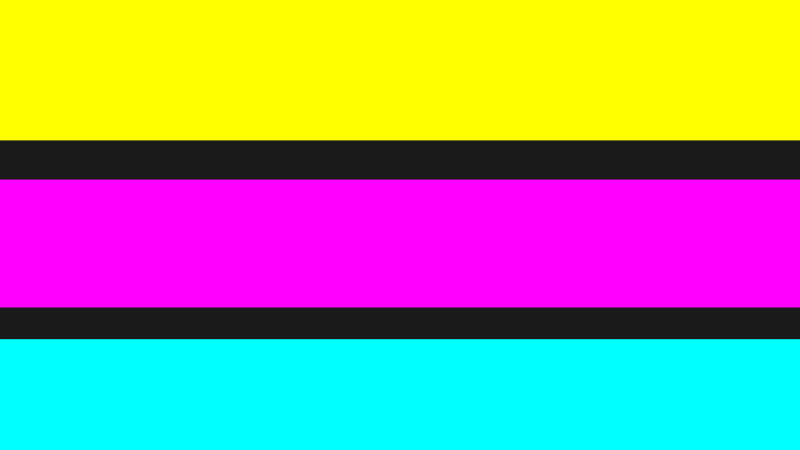

Polaroid was well known for making photographic paper with color layers used in instant photography. In the 1990s, the company was looking for something new. The Zink paper was the result. The paper has three layers of amorphochromic dyes. Initially, the dye is colorless, but will take on a particular color based on temperature.

The key to understanding the process is that you can control the temperature that will trigger a color change. The top layer of the paper requires high heat to change. The printer uses a very short pulse, so that the top layer will turn yellow, but the heat won’t travel down past that top layer.

The middle layer — magenta — will change at a medium heat level. But to get that heat to the layer, the pulse has to be longer. The top layer, however, doesn’t care because it never gets to the temperature that will cause it to turn yellow.

The bottom layer is cyan. This dye is set to take the lowest temperature of all, but since the bottom heats up slowly, it takes an even longer pulse at the lower temperature. The top two layers, again, don’t matter since they won’t get hot enough to change. A researcher involved in the project likened the process to fried ice cream. You fry the coating at a high temperature for a short time to avoid melting the ice cream. Or you can wait, and the ice cream will melt without affecting the coating.

The pulses range from about 500 microseconds for yellow up to 10 milliseconds for cyan. The dyes need to not erroneously react to, say, sunlight, so the temperature targets ranged from 100 °C to 200 °C. A solvent melts at the right temperature and causes the dye to change color. So, technically, the dye doesn’t change color with heating. The solvent causes it to change color, and the heat releases the solvent.

It works well, as you can see in the short clip below. There’s no audio, but the printer does make a little grinding noise as it prints:

The History

Zink started as research from Polaroid. The company’s instant film used color dyes that diffuse up to the surface unless blocked by a photosensitive chemical. The problem is that diffusion is difficult to control, so they were interested in finding another alternative.

Chemists at Polaroid had the idea of using a colorless chemical until exposed to light. They would eventually give up in the 1980s, but revisited the idea in the 1990s when digital photography started eroding their market share.

One program designed to save the company was to build a portable printer, and the earlier research on colorless dyes came back around. Thermal print heads were already available. You only needed a paper showing different colors based on some property the print head could control.

The team had success in the early 2000s. A 2″ x 3″ print required 200 million pulses of heat, but the results were impressive, although not quite as good as they needed to be for a commercial device. Unfortunately, in 2001, Polaroid filed for bankruptcy. The company changed hands a few times until the new owner decided it was too expensive to continue researching the new printer technology.

A New Hope

The people driving the project knew they had to find a buyer for the technology if they wanted to continue. Many companies were interested in a finished product, but not as interested in a prototype.

They were using a modified but existing thermal printer from Alps to demonstrate the technology, and when they showed it to Alps, they immediately signed on as a partner to make the hardware. This was enough to persuade an investor to step up and pull the company out of what was left of Polaroid.

Calibration

Of course, there were trials, but the new company, Zink Imaging, managed to roll out a commercially viable product. One problem solved was dealing with the slightly different paper between batches. The answer was to have each pack of paper have a barcode on the first sheet that the printer uses to calibrate itself.

Zink’s business model involves selling the paper it makes. It licenses its technology to companies like Polaroid, Dell, Kodak, and HP, which then have the usual manufacturing partners build the printers. Search your favorite retailer for “zink printer” and you’ll find plenty of options. The 2″ x 3″ paper is still popular, although you can get 4″ x 6″ printers, too.

Of course, saying it is inkless isn’t really true. The “ink” is in the paper and, as you might expect, the paper isn’t that cheap. On the other hand, inkjet ink is also expensive, and you don’t have to worry about a printer clogging up if it is unused for a few months.

More…

While Skymall no longer sells from airplanes, their YouTube channel shows a high-level view of how the printer works in a video, which you can see below.

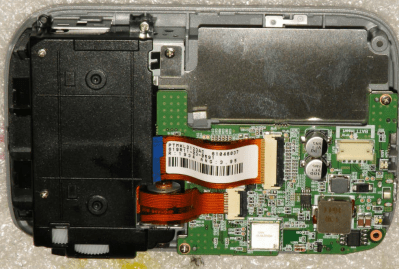

If you were hoping for a teardown, check out the FCC filings to find plenty of internal pictures (we’ve mentioned how to do this before).

We are always surprised these aren’t more common. Do you have one of these printers? Let us know in the comments. The best use we’ve seen of one of these was in a fake Polaroid camera. If you really want nostalgic photography, break out your 3D printer.

The CMY temperature driven layering is a slick concept.

Did I miss it in somewhere? Where does the black come from? (Assuming paper starts out white).

Probably just fully saturates all colors to approximate black.

Based on the poor black levels in the prints, I agree. My daughter has a camera with one of these printers in it. It’s mostly a novelty.

What’s the cost like compared to thermal label paper? I could see this being pretty useful for a variety of things if they cost isn’t outlandish.

it really isnt worth it. A canon Selphy is a far better alternative.

I had one of these years ago, shortly after my wife moved to the UK my mum used it to print a bunch of pictures of us she’d taken and made a collage out of them.

20 years later, the colours have really faded, much much more than ordinary photographs from the same time or older.

The printer itself was small, battery-powered, and portable, so it could be good fun to take out and play with, but not so much for making something you want to last.

Clicked the report comment by mistake – was on the iPhone, and can’t unreport it

That was my first question about this. I’ve saved receipts that just go blank after awhile.

You reminded me of a cool trick with old receipts that have faded to nothing. If you heat the whole receipt with an iron, the parts that have faded to white will stay white, while the rest will turn black. So you end up with an inverted copy of the original. White text on a black background.

If desired, you can scan then scan it and invert it again in Gimp or whatever.

That could be a lifesaver in the right circumstances, thanks!

Beat me to it, nice work.

I’ve got bags of components from Farnell that are almost unreadable now too, I don’t know if it’s just age or UV or heat or a combination but it feels like a bit of a weakness.

Sadly they do indeed not last (not tried storing them behind glass though, maybe UV is the problem) but as long as you accept that they great fun.

I give them as presents to children.

In this case, the collage is behind glass and on my living room wall. Looking at it right now it looks like maybe just the yellow layer has faded, the reds and blues look present.

I don’t know if that’s because yellow is the top layer or if it’s some attribute of the yellow ink. It intuitively makes sense that the top layer might fade more with the lower layers somewhat protected, but I’d be lying if I said I had any more knowledge than having printed some photos with one!

I got a Mi Photo Printer on aliexpress, thanks to this post now I know why some photos are printed with a bluish tint on hot days (which being Brazilian, is very frequent)

I have an HP Sprocket, and I really enjoy it.

At a conference or convention, I often get pictures of people at the bar-con, and pass out prints. When people find out the prints are actually stickers, they go wild.

I also take pictures of the group when playing my favorite board games, and put them into the box lid. Often other players will ask for a copy, and I print it right there.

Sure, it’s not archival quality, but it’s fun.

Oh, and the granddaughters love them, too.

Those sound like perfect use cases: capturing the moment.

We can do that so easily now with our phones, but there’s something different about having output that doesn’t disappear into the cloud and doesn’t require not-yet-obsolete technology to enjoy.

The issue is fading, which these do pretty badly. You’ll want to scan any you take. I’m interested in seeing what can be done about that, but the multilayer aspect likely means most will be unrecoverable.

They’re wasteful but dye sublimation can be pretty compact and, theoretically, outlasts most other forms of printing. I have a larger Canon one and, because there’s no dithering, the 300 dpi looks much better than higher resolution inkjet prints. Kodak and Polaroid ‘make’ compact versions.

Just don’t try to laminate it.

The SX70 process this was supposed to replace made prints that haven’t faded after 45-50 years. The zinc project was a big factor in Polaroid going bankrupt. Fuji still sells a tone on instant cameras and film.

My wife often uses a Polaroid-branded version of a Zink printer to print out pictures of people or events to augment her journal… the battery operation, size of the photo and sticker backing makes these a perfect companion.

Have insurance adjusters switched to these? Like a Polaroid their authenticity would be indisputable.

Eh, not really. These are digital prints, after all. Whatever image, however modified, you send to them gets printed.

Even genuine Polaroids were easy to “fake”. I had a photo buddy who took great delight in putting a Polaroid pack under an enlarger to make images that clearly could not have come from a SX-70.

Yeah I used to a magic trick with a Polaroid camera, taking an instant photo of an audience volunteer that included their chosen card floating above their head.

Whatever you can do in Photoshop was done on film before Photoshop existed.

I forgot to point out I did it live in front of an audience. An audience watching trying to catch me doing something fishy. One can do fake photos with a Polaroid even in front of live witnesses who are trying to catch any shenanigans.

Sounds fun for a magic trick.

Let me guess, you pre exposed only the card on the first photo?

Oh, maybe a shriked down version of the card stuck to the optics of the camera?

I don’t know why I ask, a magician never reveals its tricks = P

They are fun as instant cameras at parties, sure, but the tiny print size and so-so quality for every print I’ve seen makes me pass on buying a printer.

I’m still using my 2008 Canon Selphy dyesub and still love it. Media is still available and not outrageously expensive ($0.35 per 4×6 print), and print quality and longevity is great. Beats Zink on pretty much every metric except it’s hard to print while walking.

Anyone happen to know whether the Zink paper uses BPA? I ask because I remember thermal paper for receipts use it.

Canon makes both the Ivy Printer (prints 2 x 3 via Bluetooth) and the Ivy Camera (a 640×480 camera that takes the picture and immediately prints it, or you can also save to a MicroSD at the same time; picture quality leaves much to be desired). I received the camera from Canon as a survey premium and later bought the printer-only unit.

Challenge: Hack a 3D printer to produce an image on this paper. Sure, it might be crude as a hell 🫠

On the topic of “inkless” printing: I once read in an old electronics magazine (How old? The article was by Hugo Gernsback) about a little experiment called the Electric Pencil (no relation to the early word processor). It was litmus paper in a solution, written on with a nail that had a voltage applied. The electrolysis at the point of contact made the solution acid or alkaline, I can’t remember, so the paper changed color. It struck me that this could work as a printhead; all you need is a line of electric contracts. You don’t even need a thermal element. And you could erase and reuse the paper by wiping it down with a neutral solution. And it would be a lot more stable than thermal paper.

The downside is dealing with wet paper. You’d have to moisten it enough to be reactive then dry it enough to handle.

There used to be printers exactly like this, described as “wet toilet paper” for taking ‘screenshots’ of early CRT Terminals for mainframe/minicomputers – built into the monitor, beside the screen. However, now that I’ve said that I can’t find a single reference online – I definitely remember reading up about one, but there’s a chance I imagined the whole thing. Someone else back me up here!

For monochrome output on standard paper, one could try putting a sheet into a laser cutter at reduced power, to produce brownish-on-white output. With an optical feedback in place, this might even give consistent results all over the sheet. If anybody did such experiments, I would love to know.

I’ve tried this before with my K40. Main takeways from it are: -it’s more consistent than you expect, a 4×6″ area didn’t look too bad -resolution isn’t great, I’ve not gone beyond 3-4 lines/mm -it’s really slow, like 10 minutes per image slow. I have a small blue laser too and that one would be even more slow. -it’s hard to get the image dark enough so that it marks the paper but doesn’t cut fully through it -the finished product smudges easily because the charred areas don’t really stick to the paper that well -it’s really easy to set the sheet of paper on fire!

Just a thought- how about if you soaked the sheet of plain paper in vinegar or lemon juice and let it dry. Then run it through the laser.

As I recall, you can write with “invisible” ink such as lemon juice or vinegar and then “develop”the image in an oven. The lemon juice seems to create a more thermally sensitive area on the paper. Then it might be able to respond to the heat of the laser without charring all the way through. As I recall the developed image is brownish coloured, so it might have a nice sepia tone effect.

I have a Polaroid branded Bluetooth Zink printer and I love that thing.

Yeah they’re not very good compared to real photo printers but spitting out credit card sizes colour stickers will never not be fun.