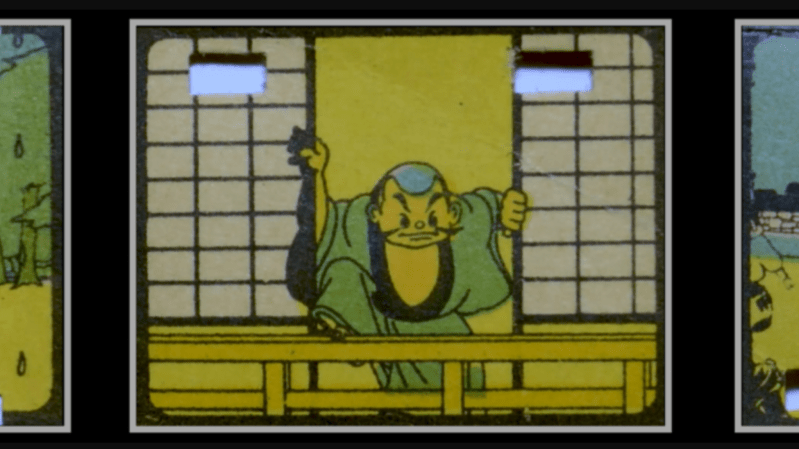

In the 1930s, as an alternative to celluloid, some Japanese companies printed films on paper (kami firumu), often in color and with synchronized 78 rpm record soundtracks. Unfortunately, between the small number produced, varying paper quality, and the destruction of World War II, few of these still survive. To keep more of these from being lost forever, a team at Bucknell University has been working on a digitization project, overcoming several technical challenges in the process.

The biggest challenge was the varying physical layout of the film. These films were printed in short strips, then glued together by hand, creating minor irregularities every few feet; the width of the film varied enough to throw off most film scanners; even the indexing holes were in inconsistent places, sometimes at the top or bottom of the fame, and above or below the frame border. The team’s solution was the Kyōrinrin scanner, named for a Japanese guardian spirit of lost papers. It uses two spools to run the lightly-tensioned film in front of a Blackmagic cinematic camera, taking a video of the continuously-moving film. To avoid damaging the film, the scanner contacts it in as few places as possible.

After taking the video, the team used a program they had written to recognize and extract still images of the individual frames, then aligned the frames and combined them into a watchable film. The team’s presented the digitized films at a number of locations, but if you’d like to see a quick sample, several of them are available on YouTube (one of which is embedded below).

This piece’s tipster pointed out some similarities to another recent article on another form of paper-based image encoding. If you don’t need to work with paper, we’ve also seen ways to scan film more accurately.

Thanks to [Yet Another Robert Smith] for the tip!

How did these film originally get viewed?

I was also wondering about this. There’s reference to a paper called “The Smell of Burnt

Paper: Digitization of Reflective Paper Films and the Transition

Period of Animated Films” by Yuka Tamamura, Hikaru Nemoto, Hiroshi Sato, but I’ve not found it (I’ve not tried very hard.)

This article (https://wp.nyu.edu/orphanfilm/2024/04/01/japanese-paper-films/) states “which also sold the means to view the films in the form of small hand-cranked projectors”, so I assume a bright light shone on the paper film and was reflected through a lens. Would be nice to see an original viewer.

I think it would have been a device similar to the illuminated paper flip “movies” that were common in the rest of the world. The indexing holes at the top would suggest they flipped around, which was the most intuitive way to cycle through frames without a feed

I found one picture of a paper film projector that looks like a miniature hand cranked movie projector, but the image was on pinterest so, source unknown, reliability dubious.

Either way, it’s perfectly feasible to project images by shining a flashlight through parchment paper and focusing an ordinary magnifying glass on the paper to throw the image on a wall. We played with such as kids – just needs a fairly dark room and a close distance to the wall to see much anything. With a good lens, it could throw across maybe 4-5 feet. It’s a toy similar to those modern ones used to project a cellphone screen on a wall.

If they were made for flip books, they wouldn’t have perforations – they’d be glued in with strips of paper along one edge.

And, the light is indeed shone through the paper – the reflection is not strong enough to be seen on the wall. We tried that back in the day, didn’t work. White parchment paper (vellum) or other thin non-waxed paper (Crêpe paper, very fragile) is thin enough to transmit light, and it improves if you oil the paper – but then the colors will run or won’t stick in the first place. Ordinary copy paper will work too, if you have a strong flashlight and a completely dark room.

We got the idea after seeing a movie about some kids trying to become movie producers, but they had no film or cameras, so they did exactly that and made a magic lantern type of projector where the pictures aren’t animated but simply rolled in and out of view like a slideshow.

About 1970 I tried using B&W photographic enlarging paper as a negative in an 8×10 field camera. The varying optical density of the paper caused poor image quality: a mottled image. Modern plastic based photographic paper might be more uniform, but might also be more opaque.

I wouldn’t be surprised if the Japanese had developed a special paper for just this purpose, done in a manual process that takes 10 years to train until you’re good enough to pass for an apprentice to the single shop that makes it. Yet somehow they would have managed to make a million copies at a cost of 100 yen each.

The animation cells would have been wood-block printed, which itself takes ages as each frame needs to be carved into wood using hairline-fine tooling, several times over for each color. No four color process – every color is a separate block, and you’re working complicated images at the scale of a postage stamp.

If you’re doing animations, the uneven light transmission doesn’t really matter because it’s a random pattern that averages out with persistence of vision. The actual paper needs to advance around 12 frames a second to maintain flicker free viewing under low light, but you could animate on three or four, meaning that each individual strip of paper could simply repeat the same image.

called “The Smell of Burnt Paper: Digitization of Reflective Paper Films

The clue is in the title “Reflective Paper”

The epidiascope – a reflective overhead projector – was still a thing when I was a kid

Would need a blinking light lantern then , eh?

If they are going to scan the film while in motion then they might as well use line scanning in stead of areal scanning. This would have the added advantage of eliminating the resolution loss due to the Bayer filter.

They have multiple images of the same frame at different positions on the sensor, which can be stacked up to remove sensor noise, dead pixels, uneven backlight or light transmission, and the bayer pattern all at the same time.

Stacking them up will remove some forms of sensor noise and increase others. Depending upon the position relative to the bayer filters it may or may not decrease the resolution loss due to the bayer filter.

On their web site, they say “As such, you will see defects, dirt, torn perforations, ink spills, scribbles, and even fingerprints,” so I assume that, as I would expect, the reason for a preservation project is to share the material with the world? No? Out of the 215 films that they claim to have “preserved,” I only see two short clips on their youtube channel. They mention “Follow our Bluesky account… to see HIGHLIGHTS of preserved films as we process them” but no mention of viewing completed films.

“Follow our Bluesky account… to see HIGHLIGHTS of preserved films as we process them” but no mention of viewing completed films”

This makes me wonder if we have stepped into a new era of scam and weasel wording. ☹️

PSA:”You wouldn’t print out a movie?”

This seems to be the same, or very similar, to the scanning of paper prints that used to be required to copyright a motion picture in the US. Paper prints have survived the original nitrate films.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paper_print

In the 1950s and early ’60s the cheapest B&w roll film was from a mail-order processing lab in Glasgow and they sent a new roll of film back with your snaps – hence their name ‘Gratispool’. They used a paper backed film which could not (or would not) be processed by “normal” labs. They delivered enlarged prints at lower cost that the contact prints from the High street labs. I tried printing some of the negatives, but the quality was ‘disappointing’ or worse. That could be down to my lack of processing skills, but I guess they had a more specialised enlarged with front illumination rather like an epidiascope.