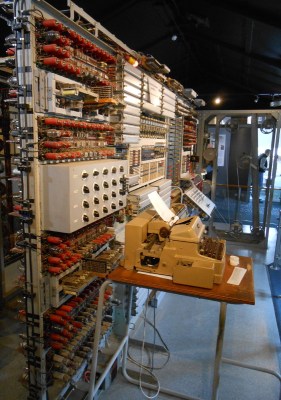

Back in 2016, we took you to a collection of slightly dilapidated prefabricated huts in the English Home Counties, and showed you a computer. The place was the National Museum of Computing, next to the famous Bletchley Park codebreaking museum, and the machine was their reconstruction of Colossus, the world’s first fully electronic digital computer. Its designer was a telephone engineer named Tommy Flowers, and the Guardian has a piece detailing his efforts in its creation.

It’s a piece written for a non-technical audience so you’ll have to forgive it glossing over some of the more interesting details, but nevertheless it sets out to right a long-held myth that the machine was instead the work of the mathematician Alan Turing. Flowers led the research department at the British Post Office, who ran the country’s telephone system, and was instrumental both in proposing the use of electronic switches in computing, and in producing a working machine. The connection is obvious when you see Colossus, as its racks are the same as those used in British telephone exchanges of the era.

All in all, the article makes for an interesting read for anyone with an interest in technology. You can take a look at Colossus as we saw it in 2016 here, and if your interest extends to the only glimpse the British public had of the technology behind it in the 1950s, we’ve also taken a look at another Tommy Flowers creation, ERNIE, the UK Premium Bond computer.

It’s good to see the more widespread recognition this man rightly deserves.

There’s a huge new mural of Tommy Flowers on the end of the Colossus gallery building at the museum now. I was actually at the museum at a fix-a-thon event when the article was published. It was a pleasure to read it in the very place where his machines were installed.

That sound like a logical fallacy(?) to me (what’s the right term? – sth. like “correlation is not causation”).

Were those racks ONLY available for British telecom?

Could anyone (any company) buy those racks too?

I mean it may be true but “not” with the limited information in the article.

Maybe it’s obvious for Brits because the racks and who used them is common knowledge over there.

Yes, I suppose it’s possible for any other telecommunications company in the UK at that time to buy and use those racks.

It’s logically possible, but with the exception of Hull Corporation there were no other telecomms companies in the UK. The GPO had a state monopoly.

Whoosh!

It’s a connection not a logical proposition.

??? the supposed obviousness of that “connection” is what I’m questioning.

Not the connection between “Tommy Flowers” and “Colossus” itself – just if/how the use of those racks is supposed to make that connection obvious at all.

I assume the people working at Bletchley Park would have had access to pretty much whatever they wanted – including those telephone racks – not matter if anyone worked for the British Post Office or not / or who from the British Post Office worked on Colossus.

They were manufactured in house for the GPO. Fun factoid, when TNMOC at Bletchley needed some new ones to build one of their machines (might not be Colossus), I was told they got them made by Marshall guitar amps, who are just down the road.

Oaky, so the GPO (General Post Office, had to look that up) build the racks mostly/only for themselves.

I know I’m pedantic here but I still find that sentence odd. The usage of those racks makes a connection between Colossus and GPO obvious, but not between Tommy Flowers and A) Colossus or even B) his employment at the GPO.

It’s not pedantic. I think you are being deliberately obtuse.

This kind of rack was more or less a standard. So, simple and cheap to get it to initiate a “workbench” at low cost.

They were used even long after war. I think they will be used in aircraft simulator too (in the 60/70s era. The Concorde simulator has quite similar technologies. And the french Concorde simulator was done by LMT – Le Materiel Téléphonique – and racks are quite similar to Colossus.

Wow, I did a search for “Colossus emulator” and found this bunch of info: https://github.com/gchq/CyberChef/wiki/Colossus

The Colossus is not really a general purpose computer. It can run an algorithm with a certain start condition and results in a certain end condition. After that, the results need to be written down, a new algorithm needs to be set up, and the results of the previous run can be fed as a new start condition.

Anyway. There is an emulator: https://www.virtualcolossus.co.uk/HBlock/

Learning how to operate the Colossus to make it do something useful for modern days, seems unrewarding. The learning curve is steep, and Colossus was made for only one purpose: breaking Lorenz-machine encrypted messages.

There’s also a Lorenz-machine emulator, here: https://lorenz.virtualcolossus.co.uk/Lorenz3D/

So you can encrypt a message on the Lorenz emulator and then try your hand at decrypting it with the Colossus emulator. :D

Running until completion is how modern general purpose computing works as well. Colossus had jump and conditional jump instructions so looping forever was not a problem.

Probably the language of the people who built and operated Colossus is distracting here as they were mathematicians and engineers whose terminology was about algorithms, the nomenclature of computing hadn’t been built up yet.

I didn’t dive deep enough into it, to be honest. But I got the impression that the system did not have a central general purpose random access storage (e.g. ram). It just has bunches of registers that each had their specific uses.

So there are input registers to set start conditions, and output registers to hold results. But there is no way to copy the output registers to the input registers and continue processing with a new algorithm. Well, other than the operator doing that manually.

A proper general purpose computer would be able to copy the output register values somewhere into storage, and would be able to copy the contents of that ram back into the input registers and continue processing with the next procedure. I think that that’s the missing link.

But, as I said, I didn’t read all the details. The machine itself, as a computer, is not too complex. Apparently the whole system contained some 2.500 radio tubes. A system using the full Intel 4004 chipset will contain over 9.000 transistors, almost 4 times as many.

But the user-interface of the Colossus is quite daunting…

Interessant. I wonder if a port to the Zuse computers would be possible.. ;)

Thanks for mentioning my simulations, I’m pleased you enjoyed them. There is a later version of the Colossus simulation in full 3D you can walk around and use at https://virtualcolossus.co.uk/colossus3d plus many other including Enigma, the Bombe, an M-209 and a fully working Pilot ACE which is the computer Alan Turing designed after the war. He would have seen what the incredible Tommy Flowers designed and realised this was just a step away from the perfect hardware to build his computer he invisaged. I also wrote the wiki information & Colossus /Lorenz recipes at cyber chef :) currently working on a full working version of the SG-41 known as the Hitler Mill which would potentially have replaced Enigma. Hopefully coming later this year. Also, there’s a version of ERNIE you can use and learn about how it worked. Martin Gillow, virtualcolossus.co.uk

Collusus was not a general purpose computer in the modern sense, being designed for one purpose. However experiments at the latter end of the war, showed it could be re-puposed to do simple arithmetic tasks. What was missing was the programming interface and the ability to generate machine code…that was for the future

I visited Bletchley Park and wandered into the side building in the ajoining Computer History Museum, an older gentleman behind the counter spoke for 45 mins about near every detail of how Tommy designed and built this thing, before it was sadly destroyed at the end of the war to protect it’s secrets, goes into next room containing this fully functioning replica looping paper tape, it’s really something to see in person, the mechanical, noise, motor sounds, glow and warmth from the valves…

https://youtu.be/9HH-asvLAj4

Yep, there are a lot of lovely enthusiastic staff at the Computer History Museum. I went there with a friend a few years ago, she asked me about the slide rules they have there, as I was briefly explaining them one of the staff came and talked at length about slide rules, not telling me anything I didn’t know, but also way beyond the level of interest of my friend.

I’m sure most of the people there could talk at length about their areas, and I love that, the only problem at the time was that we were in timed slots due to the Covid restrictions.

Actually (and it’s in the article), a couple of the Colossus computers were kept at GCHQ after the war.

(second try)

The National Museum of Computing is well worth a visit and watching Colossus run really is a smile generator.

The last paragraph was to me very touching. This man knew of his accomplishment. But he gave his nephew sound information. I try to instill this into my son when he has what he thinks are original ideas. I encourage him to keep trying. They’re all good, and it’s by using imagination and skill that we take the leaps forward that we do.

No mention of LEO? By 1952 it was more advanced than the machine it was partly based on, EDSAC. And it’s LEO that transformed the concept of computing into a tool for commerce, governments and even research.

I’ve been to Bletchley many times and I think they’ve done super job of keeping the history of Bletchley, ENIGMA, COLLOSUS and LORENZ alive. They have some LEO artifacts as well including, I think, a mercury delay line unit from a LEO I.

Sadly, I was too late in the game to see or work on a LEO I or LEO II, but I did have the pleasure of working on the LBJCC LEO III in 1967

Hmm, an engineer won the war eh, must make all the millions of soldiers feel really silly for getting involved then.

Mind you these days it really is silly to go to a battlefield, where it’s full of automatic weapons and remote controlled ones and all you can do really as a human is make a red mess – well red if you are ‘lucky’ and aren’t fried into a brown/black mess of course.

Don’t forget R.V. Jones. His book ‘Most secret war’ is an amazing insight.

I’ll second that!