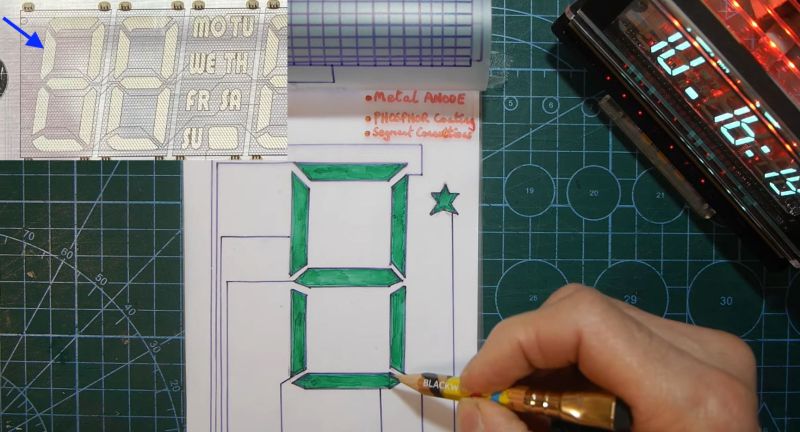

After having been sent a vacuum fluorescent display (VFD) based clock for a review, [Anthony Francis-Jones] took the opportunity to explain how these types of displays work.

Although VFDs are generally praised for their very pleasant appearance, they’re also relatively low-power compared to the similar cathode ray tubes. The tungsten wire cathode with its oxide coating produces the electrons whenever the relatively low supply voltage is applied, with a positively charged grid between it and the phosphors on the anode side inducing the accelerating force.

Although a few different digit control configurations exist, all VFDs follow this basic layout. The reason why they’re also called ‘cold cathode’ displays is because the cathode doesn’t heat up nearly as hot as those of a typical vacuum tube, at a mere 650 °C. Since this temperature is confined to the very fine cathode mesh, this is not noticeable outside of the glass envelope.

While LCDs and OLED displays have basically eradicated the VFD market, these phosphor-based displays still readily beat out LCDs when it comes to viewing angles, lack of polarization filter, brightness and low temperature performance, as LC displays become extremely sluggish in cold weather. Perhaps their biggest flaw is the need for a vacuum to work, inside very much breakable glass, as this is usually how VFDs die.

Check one out under a microscope.

I dunno…. I managed to kill one DED by mis-wiring it and turrning the controller on it into a lump of useless plastic and sand. :( (in my defense, the pinout for that module was not well documented. )

It’s not hard to make your own controller for one. Chips like the HV5812 and HV518 are very useful for that.

in 2001 or so I found a 16 by 2 line alphanumeric fluorescent display just out on the street being thrown away in Brooklyn. I did some testing and determined it had a latching parallel eight-bit input, and I soon had it hooked up to a PC displaying arbitrary messages. that was easy to hook up using an ISA bus, but modern PCs have nothing like it. (a parallel printer port is similar, but it has a latch that is unneeded when the latch is supplied. that counts as one of my best saves from the trash, in that it was a valuable item and it also required some technical know-how to use.

For a modern PC, you just hook up a $1.50 ESP32 module to the display, write a little Arduino code, and control to it over BLE.

Or Wi-Fi. Put a webserver on it that has some simple REST endpoints, or even simply CGI, and control it with a web browser.

If I remember correctly, to interface with an ISA bus, you’d use a 74LS245 (bidirectional data bus buffer), two 74LS244’s (address bus buffering), a 74LS688 (address decoding), a pin header (for setting the base address), a 74LS32 and a 74LS08 to manage I/O read/write direction and tri-state of the 74LS245.

I think a $1.50 ESP32 is a lot cheaper. :) Ok, you’ll also need a 3.3V regulator, costing about $0.50. I assume that you already have a box of unused wall warts, like everyone else of us.

So the end price for using an ESP32 is actually about $2.00, maybe $2.50. Which is cheaper than the combined components you need to interface to an ISA bus.

The software is almost trivial, if you use Arduino and some of its excellent and easy to use libraries. Examples always included.

(But really, don’t use the Arduino development for anything complex, you’ll want to shoot yourself after a while. :D Use PlatformIO (which is based on VScode))

the glory of modern microcontrollers is their easy-to-connect serial interfaces. whenever i have to hook up eight GPIO pins to make a parallel port on an ESP32, i feel like i have crossed some sort of digital Rubicon that really should permanently separate classic tech (like the Commodore 64 or the ISA bus) from what we have today. that said, it would be great to make a stand-alone ISA bus reachable by WiFi that I can plug all my esoteric dumpster-dived ISA cards into.

I bought my current bench multimeter (a Fluke model 45) in part because of the VFD display. My old one had an LCD and was nowhere near as easy to read. Plus the 45 is a dual display model!

VFDs usually die from dimming over time. When constantly on, they can last a decade or two, but they’re in a lot of vintage audio equipment that’s much older than that.

I have a Bose Wave with a VFD that is quite dim. I was thinking it might be due to electrolytic capacitor failure, since it dates to the early 2000s when electrolytic capacitors suffered from a plague. But perhaps I am just seeing normal deterioration. Thoughts?

The driver failing can dim the display, and if it hasn’t seen a lot of use a faulty capacitor is the most likely culprit, but if it has been in use since the early 2000s, there’s likely not much you can do but replace it. Fortunately the Bose Wave was pretty common, so you can get them used for cheap.

An audio streaming product called SqueezeBox 3 has a gorgeous Noritake MN32032A 320×32 pixel, grayscale, bitmapped graphics display VFD on it. One of my favourite “apps” was the VU meter which tracked the music and livened up the display. SlimDevices has ended web server support of that product. Home server based controls live on to drive the SB3. Noritake was a top manufacturer for quality VFD.