While it has become a word, laser used to be an acronym: “light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation”. But there is an even older technology called a maser, which is the same acronym but with light switched out for microwaves. If you’ve never heard of masers, you might be tempted to dismiss them as early proto-lasers that are obsolete. But you’d be wrong! Masers keep showing up in places you’d never expect: radio telescopes, atomic clocks, deep-space tracking, and even some bleeding-edge quantum experiments. And depending on how a few materials and microwave engineering problems shake out, masers might be headed for a second golden age.

Simplistically, the maser is — in one sense — a “lower frequency laser.” Just like a laser, stimulated emission is what makes it work. You prepare a bunch of atoms or molecules in an excited energy state (a population inversion), and then a passing photon of the right frequency triggers them to drop to a lower state while emitting a second photon that matches the first with the same frequency, phase, and direction. Do that in a resonant cavity and you’ve got gain, coherence, and a remarkably clean signal.

The Same but Different

However, there are many engineering challenges to building a maser. For one thing, cavities are bigger than required for lasers. Sources of noise and the mitigations are different, too.

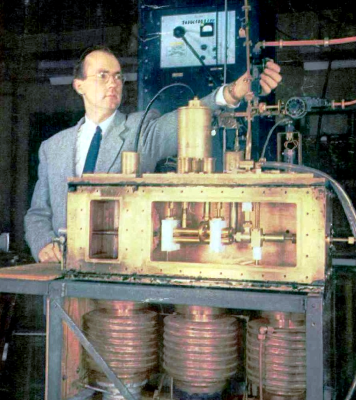

The maser grew out of radar research in the early 1950s. Charles Townes and others at Columbia University used ammonia in a cavity to produce a 24 GHz maser, completing it in 1953. For his work, he would share the 1964 Nobel Prize for physics with two Soviet physicists, Nikolay Basov and Alexander Prokhorov, who had also built a maser.

Eclipsed but Useful

By 1960, the laser appeared, and the maser was nearly forgotten. After all, a visible-light laser is something anyone can immediately appreciate, and it has many spectacular applications.

At the time, the naming of maser vs laser was somewhat controversial. Townes wanted to recast the “M” in maser to mean “molecular,” and pushed to call lasers “optical masers.” But competitors wanted unique names for each type of emission, so lasers for light, grasers for gamma rays, xasers for X-rays, and so on. In the end, only maser and laser stuck.

Masers have uses beyond fancy physics experiments. Trying to detect signals that are just above the noise floor? Try a cryogenic maser amplifier. That’s one way the NASA Deep Space Network pulls in signals. (PDF) You cool a ruby, or other material, to just a bit of 4 °K and use the output of the resulting maser to pull out signals without adding much noise. This works well for radio astronomy, too.

Need an accurate time base? Over the long term, a cesium clock is the way to go. But over a short period, a hydrogen maser clock will offer less noise and drift. This is also important to radio astronomy for building systems to use very long baseline interferometry. The NASA network also uses masers as a frequency standard.

All Natural

While we didn’t have our own masers until 1953, nature forms them in space. Water, hydroxyl, and silicon monoxide molecules in space can form natural masers. Scientists can use these astrophysical masers to map regions of space and measure velocities using Doppler shifts.

Harold Weaver found these in 1965 and, as you might expect, they operate without cavities, but still emit microwaves and are an important source of data for scientists studying space.

Future

While traditional masers are difficult to build, modern material science may be setting the stage for a maser comeback. For example, using nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamonds rather than rubies can lead to masers that don’t require cryogenic cooling. A room-temperature maser could open up applications in much the same way that laser diodes made things possible that would not have been practical with high-voltage tubes and special gases.

Masers can produce signals that may be useful in quantum computing, too. So while you might think of the maser as a historical oddity, it is still around and still has an important job to do.

In a world where lasers are so cheap that they are a dollar-store cat toy, we’d love to see a cheap “maser on a chip” that works at room temperature might even put the maser in reach of us hackers. We hope we get there.

I built a NASA funded maser test stand at college (1975, I think). Room temperature, using a gas as the medium, pumped by a 50W CO2 laser. Got it to the point that NASA would call and say ‘try this gas’, and an hour later we’d have a report.

Tried to get a CO2 pumped maser amplifier working, but that was much less successful.

Guess it didn’t get very far; we never heard anything about practical (or even impractical) implementations.

Mondial88

“Molecular amplification” makes no sense.

You haven’t heard of DNA amplification? That is most definitely molecular.

And now we need to see what we can get out of, Taser.

Toast amplification by stimulated emission of radiation? No good for science, Lone Star already jammed it. Delicious though.

One Jolt and you’re Toast.

But only if you’re in-bread.

Good One – Very clever and funny- “In-Bread” lol

That appeals to my Baser instincts.

TASER = Thomas Alva Swift Electric Rifle.

“Tom Swift” was a series of “boy genius inventor” novels and this was one of his inventions. I believe the makers of various oppressive “less lethal” devices nicked the name.

Jeebus I thought this was gonna be a TAYLOR Swift thing. Whew.

Tom Swift was my childhood (1950s-60s) inspiration and hero! Since my name is also Tom, I liked to call myself “Tom Swift”. As you can surely imagine, the mockery I received for that was intense. But I didn’t care—I had fabulous inventions to dream about. Ah, the good ol’ days… Times that later generations can’t even imagine.

This one? https://spie.org/news/6254-curved-and-self-healing-electric-discharges

We had greasers at our school! Wait, what? Oh. Nevermind.

This article would have been better if it talked about Python. How do masers relate to Python? I like articles that talk about Python.

I work with masers in a timing lab AND we use Python for data analysis and to create dashboards to monitor the masers’ performance and the telemetries 🤘

Next stop, maser CPUs. IMHO, not much remains in the way off, just technological challenges haven’t been addressed properly. Yet.

IMHO, still think photon CPUs are the real way forward. Photon CPUs coupled with the rest of the units via quantum tunneling, so quantum-tunneled bus connecting anything within the vicinity of the motherboard without the wires or PCBs. In short, invent us the Star Trek – you bring a module closer to the “react space”, ie, plug it into an empty slot with zero wires, just like in the series, fake boards with seemingly zero functionality, and then boom, it is connected to the bus and works as it should.

Scifi or not, time to move forward into the 21st century where’ve been for the last quarter century. Bring me not just RP2040/RP2350, but RP10 (nm) and RP100 (nm) – not nanometers of the transistors on the chips, RP is already at 40nm, nanometers of the wavelength of the photons shuttling to/fro, the low end of the ultraviolet, sold for the same $10 including S&H to my door.

Use a maser in a CNC rig to do fancy spot-cooking (as opposed to burning) in something, rather like a pinpoint microwave oven. Okay, I can’t offhand think of a single place where this would be useful, but there are more creative minds here than mine.

Long, long ago (’70s) I seem to remember the laser also not having a use. “The solution without a problem” comes to mind from back them.

I recall hearing the phrase “a solution in search of a problem”. Yeah, they were kind of a novelty, albeit the 10 kilobuck physics lab sort of novelty for a while.

Yeah, what greenbit said now I hear it!

“10 kilobuck physics lab sort of novelty” I don’t remember exactly what I paid (in the ’60s, when I was a teenager) for the HeNe laser tube that I got from Metrologic (being cheap, I built the power supply with scrounged parts instead of buying theirs, and went without a case), but given how poor I was it couldn’t have been more than a couple hectobucks tops. And even that required pleading for an “educational” subsidy from my mom.

“Long, long ago (’70s) I seem to remember the laser also not having a use. ” WHAT?! We were using lasers for “psychedelic” lightshows back then. In high school (’71 grad) I owned a Metrologic 0.5mW (can you imagine a power that low…) HeNe laser and got paid by local colleges to do lightshows with that, my color organs, and various other wacky toys. That even got me written up in a local newspaper as a “boy genius”, which was absurd since I borrowed many of my ideas from good ol’ Edmund Scientific.

(I bumped “Report Comment” accidentally, as I was scrolling down on my tablet. No way to undo that. Sorry.)

you’re probably getting close to designing a system that could create custom-shaped and sized diamonds and other precious and semi-precious gems.

Honestly, there’s almost certainly a use for this

plastic welding?

On the other hand could you use a beam antenna to focus and direct most of the energy from a regular microwave emitter, with a metal cage to recapture stray emissions as electrical current? A tiny focused emitter with a shielded infrared detector could make microwave ovens much more efficient and heat evenly, if there were a way to aim the microwaves without moving parts.

What every happened to photon echo memory? I thought that was going to be THE answer…and the coolest name ever…

There have been a number of papers recently on simple solid state masers, eg:

“Maser-in-a-shoebox”: A portable plug-and-play maser device at room temperature and zero magnetic field

https://pubs.aip.org/aip/apl/article/124/4/044004/3061570/Maser-in-a-shoebox-A-portable-plug-and-play-maser

and

LED-pumped room-temperature solid-state maser

https://www.nature.com/articles/s44172-025-00455-w

Even growing the crystal seems not outside the bounds of an amateur hack.

Cool thanks for the links :)

Am I the Only one that is seeing a Directional Burst of Microwave Energy, as a Hand Held Directional Weapon?..

Havana Syndrome Anyone?..

Cap

Yes.

Americans, never shy of finding the retardedness potential in any situation and embracing it.

But is microwave exposure consistent with the symptoms?

Now if only someone could work out a way to get population inversions in the 2 to 20meV range..

Well, it’s clearly possible to have a population inversion in the 2–20kHz range. Just take a walk in Manhattan.

yeah, that band is annoyingly difficult to work in for lack of sources (and detectors).

On the other hand, there also isn’t much interesting there because there are not many natural contrast mechanisms, and it’s lousy at propagating through anything.

If a suitable source and detector ever get worked out, the killer app might just be in-vacuo high speed communication: intersatellite and interplanetary.

Phase-lock a few microwave ovens for coherent RF:

Ref: section 2.3.1. Phase-Locked of Magnetron

http://www.mdpi.com/3042-5697/2/1/3

“Phaser” of star trek fame was supposed to stand for “photon maser”, i.e. a laser gun.

Really? I only ever heard of that as coming from “phased laser”, or “phased energy rectifier”.

Every maser is a photon maser… I hope Starfleet don’t say “LCD display” too.

LCDs are too high-tech for Starfleet. I mean, look how clunky their tricorders are!

Though, I’m still looking for a pocketable directed-energy weapon that can be set to “stun”.

One future super sci-fi-ish application is geothermal drilling, which I believe uses a Maser (Gyrotron) to vapourise rock https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quaise

There was news about a dynamic (Maser) wave guide suited for drilling a few years ago. Seems like this happened now. https://newatlas.com/energy/quaise-energy-millimeter-wave-drill-demo-houston/

Would a maser operating in the 30THz atmospheric window be feasible ?

Nice introduction. But someone writing about physics using °K? Kelvin temperature units are just Kelvin or K.

And “a bit of 4°K” makes no sense.

It’s not too ridiculous, degrees Kelvin were standard until the 13th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) in 1967. The official reason for the change was the shift from seeing them as degrees on a scale pegged to absolute zero to the absolute quantity of thermodynamic energy present, but that’s always seemed like a bit of a fudge. I wouldn’t be that shocked if the degree symbol being mistaken for a zero or an operator had as much to do with it as anything philosophical.

See the Nature paper on the room-temperature continuous wave maser https://www.nature.com/articles/nature25970. They used a diamond with nitrogen vacancy defects — it’s about 1/4ct, I’ve modeled all this in fusion360. It sounds fancy but basically you take a diamond that size and zap it with high voltage electrostatic discharges in a nitrogen atmosphere. This diamond sits in a sapphire cylinder inside a larger tuned copper dielectric resonator. They illuminate the diamond with a 532nm laser and they get a CW coherent microwave signal out of it. I forget the frequency but want to say 8GHz or something.

It’s more than the diamond — Dielectric Resonators are an entire discipline and there’s a really good book on it, “Dielectric Resonators (ARTECH HOUSE ANTENNAS AND PROPAGATION LIBRARY)” by D. Kajfex (Author), Pierre Guillon (Editor).

I tried to get the materials to reproduce this but gave up on it. I learned a lot in the process though. There’s a lot of potential for exotic outcomes with this general stack.

Setting up a PIR sensor and a salvaged maser from an old microwave as a booby trap is horrifyingly effective, practical, and safe in contrast to traditional explosive-based systems. Just conceal above an access control point that forces pausing (such as a locked door) and aim for the face, crown, or medulla. An upgrade would be adding servos, CCTV, and Raspberry Pi with an automated targeting program, plus manual mode remote operation. You also could use RFID security badges, wallet transponders, or custom jewelry (no Blutooth!) to ensure that authorized personnel can access safely.

FYI, I was a Sapper in the Army and crawled through tunnels looking for traps and otherwise searched for explosive devices, which is why my brain automatically thinks up these defensive applications- there is no cause for alarm.