When looking back on classic gaming, there’s plenty of room for debate. What was the best Atari game? Which was the superior 16-bit console, the Genesis or the Super NES? Would the N64 have been more commercially successful if it had used CDs over cartridges? It goes on and on. Many of these questions are subjective, and have no definitive answer.

But even with so many opinions swirling around, there’s at least one point that anyone with even a passing knowledge of gaming history will agree with — the Virtual Boy is unquestionably the worst gaming system Nintendo ever produced. Which is what makes its return in 2026 all the more unexpected.

Released in Japan and North America in 1995, the Virtual Boy was touted as a revolution in gaming. It was the first mainstream consumer device capable of showing stereoscopic 3D imagery, powered by a 20 MHz 32-bit RISC CPU and a custom graphics processor developed by Nintendo to meet the unique challenges of rendering gameplay from two different perspectives simultaneously.

Released in Japan and North America in 1995, the Virtual Boy was touted as a revolution in gaming. It was the first mainstream consumer device capable of showing stereoscopic 3D imagery, powered by a 20 MHz 32-bit RISC CPU and a custom graphics processor developed by Nintendo to meet the unique challenges of rendering gameplay from two different perspectives simultaneously.

In many ways it’s the forebear of modern virtual reality (VR) headsets, but its high cost, small library of games, and the technical limitations of its unique display technology ultimately lead to it being pulled from shelves after less than a year on the market.

Now, 30 years after its disappointing debut, this groundbreaking system is getting a second chance. Later this month, Nintendo will be releasing a replica of the Virtual Boy into which players can insert their Switch or Switch 2 console. The device essentially works like Google Cardboard, and with the release of an official emulator, users will be able to play Virtual Boy games complete with the 3D effect the system was known for.

This is an exciting opportunity for those with an interest in classic gaming, as the relative rarity of the Virtual Boy has made it difficult to experience these games in the way they were meant to be played. It’s also reviving interest in this unique piece of hardware, and although we can’t turn back the clock on the financial failure of the Virtual Boy, perhaps a new generation can at least appreciate the engineering that made it possible.

Cutting Edge Technology

Looking at the Virtual Boy today, it’s easy to assume that it operates on more or less the same principles as modern VR headsets, with two independent displays used to show slightly different perspectives of the same scene to the player in order to trick their brain into seeing a three dimensional image. Indeed, that’s how it would be done today if you were to create a modern version of the Virtual Boy, and is essentially how the Switch version of the system will work.

That’s because today, thanks in large part to the demands of the smartphone market, we have access to miniature high-resolution displays. But the display technology of 1995 was very different, especially when it came to consumer devices. Released just five years prior, Sega’s Game Gear did feature a self-illuminated color display — but it was far too large and energy-hungry for this type of application.

That’s because today, thanks in large part to the demands of the smartphone market, we have access to miniature high-resolution displays. But the display technology of 1995 was very different, especially when it came to consumer devices. Released just five years prior, Sega’s Game Gear did feature a self-illuminated color display — but it was far too large and energy-hungry for this type of application.

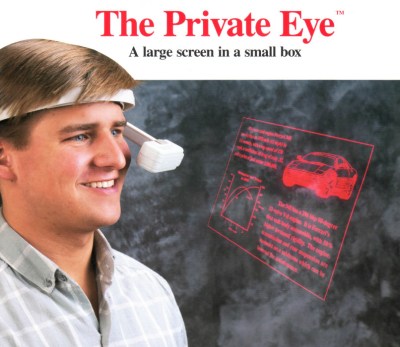

The solution ended up coming from an American company, Reflection Technology. In the late 1980s they had developed a product called “The Private Eye”, a wearable monocle display that could connect to a standard computer. Utilizing the company’s patented Scanned Linear Array technology, it had a resolution of 720×280 and retailed for $795.

Reflection tried shopping the Scanned Linear Array technology around to other companies, including Sega, but were repeatedly turned down due to its cost and complexity. Eventually Gunpei Yokoi, head of Nintendo’s R&D and legendary creator of the Game Boy, came across the device and was impressed. He believed a scaled-down version of the technology could create a new type of gameplay experience that would be difficult for competitors to match, and so Nintendo entered into an exclusive licensing agreement for the Scanned Linear Array as it applied to gaming.

More than Meets the Eye

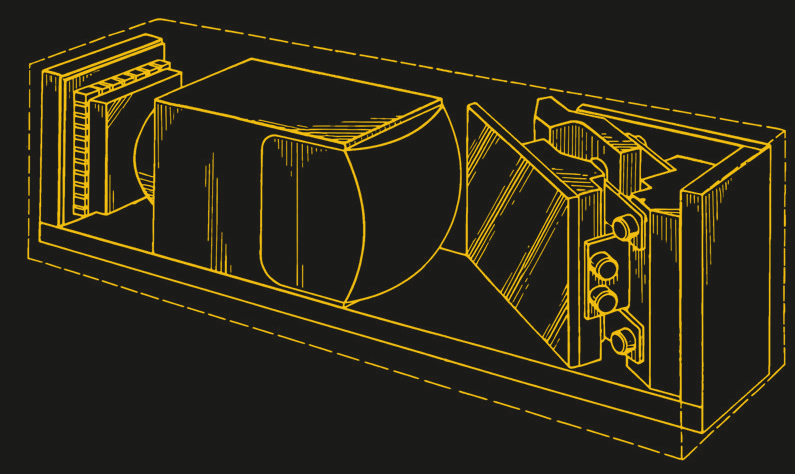

Contrary to our contemporary expectations, the Virtual Boy doesn’t have two screens. In fact, it doesn’t even have one. Instead, the Scanned Linear Array makes use of a single column of LEDs and a rapidly oscillating mirror to project an image into the user’s eye. By scanning back and forth across the eye fast enough, persistence of vision makes the viewer see a complete image.

The Private Eye used a single Scanned Linear Array element to create a 2D image in one eye, but the Virtual Boy featured two identical units to achieve its 3D effect. To bring the cost down, the resolution was dropped to 384×224, which corresponded to a column of 224 tiny LEDs for each eye. Recently The Slow Mo Guys on YouTube captured incredible footage of how the technology actually works inside the Virtual Boy, utilizing some clever video editing to demonstrate how each 1×244 LED array is able to draw out an entire frame of video.

Monochromatic Miscalculation

As impressive as the Scanned Linear Array technology was, it had a critical flaw in that it could only produce an image in shades of red. While technically you could produce a full-color image via this method, it would require a red, green, and blue array for each eye, plus the necessary optics to combine their output.

By the time the Virtual Boy was being developed, blue LEDs were available but they were not yet common, and would have substantially raised the cost of the device. But even if this wasn’t the case, there was no way to fit all six LED arrays and the required optics into the Virtual Boy. As it was, the system was too heavy to wear like a modern VR headset, and needed to be held up to eye level with a tabletop stand. The power consumption would also have been prohibitive — even with just the two LED arrays, the system could only run for approximately four hours on six AA batteries.

Despite these challenges, Nintendo reportedly did experiment with versions of the Virtual Boy that could display more colors. But in the end, just like The Private Eye that came before it, the console was only capable of a red-on-black color scheme that users found unpleasant to view for extended periods of time. As if that wasn’t bad enough for a game system, many players experienced eyestrain from the 3D imagery, and even Nintendo’s own advertisements claimed children under the age of seven shouldn’t use the system due to the potential for eye damage.

The Modern Solution

While the Switch support for Virtual Boy games will at least mean these titles get to be played by a larger audience, there’s something bittersweet about how it will work. The Virtual Boy accessory for the Switch is nothing but a hollow plastic shell with a slot for the player to insert their Switch, and for those that don’t want to spend $99, Nintendo says there’ll even be a cardboard version that accomplishes the same goal. Like Google’s phone-based VR offering, all you really need is to hold a couple of lenses and partition off each eye.

All the heavy lifting will be done in software, with the two perspectives on gameplay being displayed in a split-screen fashion. A simple and easy to implement approach that takes advantage of the Switch’s modern high-resolution widescreen display and processing power.

It’s a logical solution to a problem which once took hundreds of dollars worth of custom hardware to solve, and will undoubtedly work even better than the original version. This is especially true since Nintendo has said they plan on adding support for rendering the games in colors other than red.

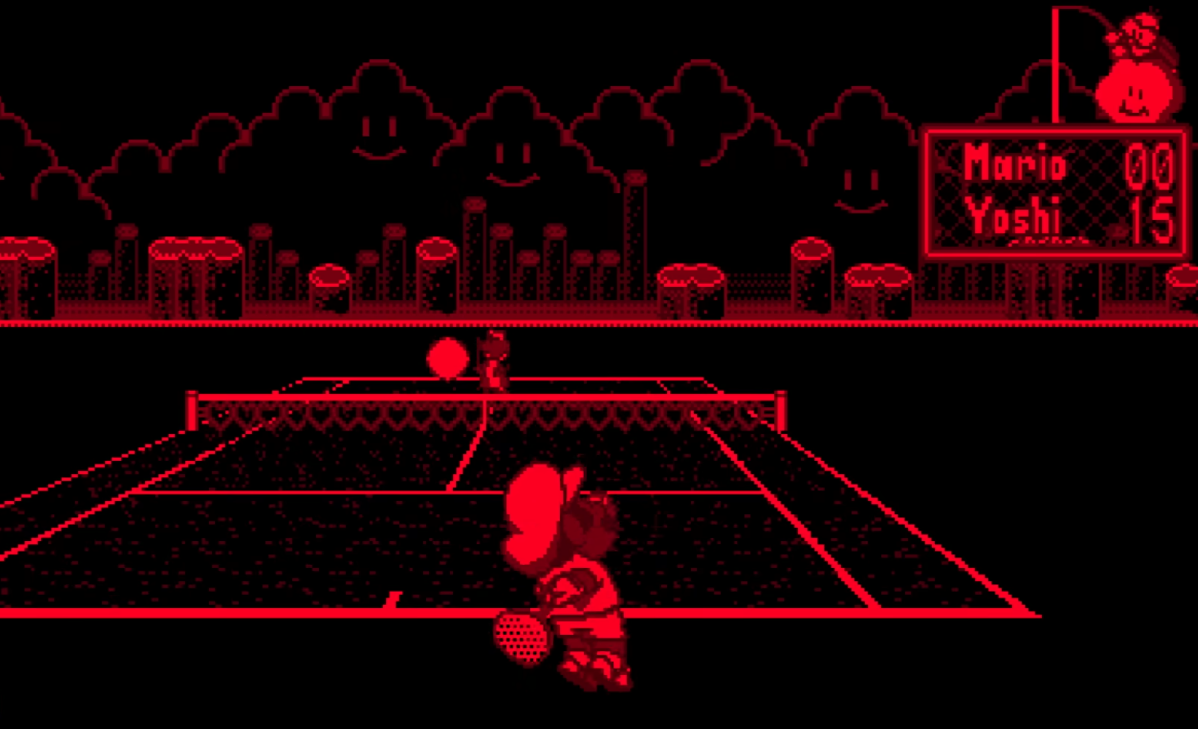

Still, it won’t be nearly as impressive as the engineering that went into the Virtual Boy itself. So if you find yourself playing Mario Tennis or Galactic Pinball through the literal rose-tinted glasses of the Switch’s upcoming accessory, take a moment to appreciate all the incredible work that went into developing the hardware capable of rendering them thirty years ago.

I have 2 original VB units (bought them new back when Nintendo clearanced them in the 90’s) and always loved the system for what it was. The display for the time was sharper than any other portable, and the sound (32bit, IIRC) was pretty damn good.

People tried making emulators but the games dont work great on a 2d screen, and it wasnt until I found on for the Quest that I really liked it, although, I would rather play on original hardware, especially since the controller is fairly odd and hard to duplicate.

I remember playing Mario Tennis for about 5 minutes on a Virtual Boy in a toy store when I was 10. I fount it really unimpressive.

Some months later, Software Etc had stacks of them on clearance for something like $24. I’ve always regretted not getting one.

You can actually emulate it in stereoscopic 3d using retroarch on an android phone, then shove it into a cheap VR headset. It works pretty well, as I recall. Apparently there’s also an emulator for the 3ds as well.

Luckily, shops like Stone Age Gamer are making accessories and repair parts for these units, as many of the displays suffer connection issues due to be stored in hot attics, and a few people have found not yet released titles and made reproduction carts (Faceball comes to mind) which play perfectly on the system.

If you really want to see it shine, there’s an emulator for the 3DS… Best way you can emulate it!

You can also emulate it in stereoscopic 3d using retroarch on an android phone and a cheap vr housing.

In some ways, yes. Though as someone who had lived through these days, I’d say that the Forte VFX1 cyber helmet and the many cheap shutter glasses for DOS PCs with VGA CRTs were available at about same time.

Games such as Descent did support LCD BIOS or similar DOS drivers.

That way, there was at least a basic hardware abstraction available.

The shutter glasses sold for PC were very affordable in comparison,

because they were just two LC filter foils that became dark.

Interface was very primitive sometimes, too.

Just three wires for left/right/ground wired to a 3,5mm plug, which plugged into a serial port dongle (using RTS, DTR, GND pins etc).

The Sega Master System used a similar type of glasses in the 80s, I think.

I guess even Amiga users had used such glasses, too.

https://segaretro.org/3-D_Glasses

By the very end of the 90s, the Elsa 3D Revelator shutter glasses were probably more memorable to many here.

The glasses supported generic Direct 3D games on Winsows 98 without requiring special support,

since the depth information usually was already there.

If I had to make a colour version of this, I would stagger 3 rows of LEDs, red, green and blue side by side, either one or two pixel widths apart and stagger the frame to show. This way it would start out showing the red (R) for row 0 (R0) of the frame and nothing for green (G) and blue (B). Then it would move the mirror one pixel, show R for R1, G for R0 and nothing for B, having G overlap the first R. Move the mirror another pixel, show R for R2, G for R1 and B for R0. Now the eye’s persistence would make R0 look like full colour.

The hardware could be the same apart from two extra sets of LEDs in each side and probably need a faster processor. I am quite aware that this would not be feasible at the time of the original Virtual Boy due to the price and availability of blue LEDs, the need for a faster processor and the steep price hike it very likely would have caused.