In 1958, the American free-market economist Leonard E Read published his famous essay I, Pencil, in which he made his point about the interconnected nature of free market economics by following everything, and we mean Everything, that went into the manufacture of the humble writing instrument.

I thought about the essay last week when I wrote a piece about a new Chinese microcontroller with an integrated driver for small motors, because a commenter asked me why I was featuring a non-American part. As a Brit I remarked that it would look a bit silly were I were to only feature parts made in dear old Blighty — yes, we do still make some semiconductors! — and it made more sense to feature cool parts wherever I found them. But it left me musing about the nature of semiconductors, and whether it’s possible for any of them to truly only come from one country. So here follows a much more functional I, Chip than Read’s original, trying to work out just where your integrated circuit really comes from. It almost certainly takes great liberties with the details of the processes involved, but the countries of manufacture and extraction are accurate.

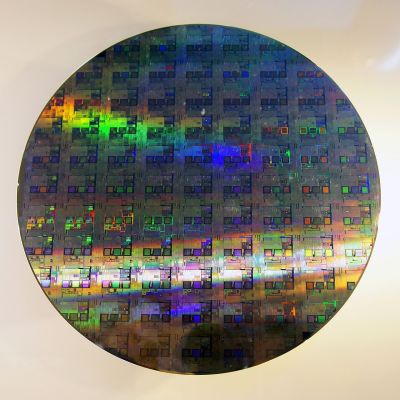

First, There’s The Silicon

An integrated circuit, or silicon chip, is as its name suggests, made of silicon. Silicon is all around us in rocks and minerals, as silicon dioxide, which we know in impure form as sand. The world’s largest producer of silicon metal is China, followed by Russia, then Brazil. So if China and Russia are off the table then somewhere in Brazil, a Korean-made continuous bucket excavator scoops up some sand from a quarry.

That sand is taken to a smelting plant and fed with some carbon, probably petroleum coke as a by-product from a Brazilian oil refinery, into a Taiwanese-made submerged-arc furnace. The smelting plant produces ingots of impure silicon, which are shipped to a wafer plant in Taiwan. There they pass through a German-made zone refining process to produce the ultra-pure silicon which is split into wafers. Taiwan is a global centre for semiconductor foundries so the wafers could be shipped locally, but our chip is going to be made in the USA. They’re packed in a carton made from Canadian wood pulp, and placed in a container on a Korean-made ship bound for an American port. There it’s unloaded by a German-made container handling crane, and placed on a truck for transport to the foundry. The truck is American, made in the great state of Washington.

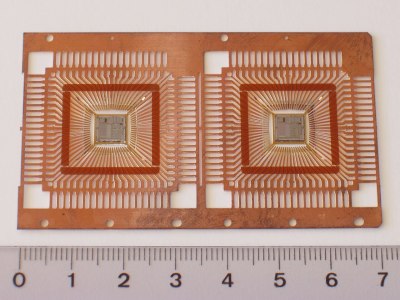

Then, There’s The Package And Leads

Our integrated circuit is the chip itself, but in most cases it’s not just the bare chip. It’s supplied potted in an epoxy case, and with its contacts brought out to some kind of pins. The epoxy is a petrochemical product, while the lead frame is either stamped or chemically etched from metal sheet and plated.

So, somewhere in the Chilean Atacama desert, an American-made dragline excavator is digging out copper ore from the bottom of a huge pit. The ore is loaded into Japanese-made dump trucks, from where it’s driven to a rail head and loaded into ore carrier cars. The American-made locomotives take it to a refining plant where machinery installed by a Finnish company smelts and refines it into copper ingots. These are shipped to Sweden aboard a German-made ship, unloaded by a German-made crane, and delivered to a specialised metal refiner on a Swedish-made truck.

Meanwhile underground in Ontario, Canada, Swedish-made machinery scoops up nickel ore and loads it onto a Swedish-made mine truck. At the nickel refining plant, which is Canadian-made, the sulphur and iron impurities are removed, and the resulting nickel ingots travel by rail behind a Canadian-made (but American designed) locomotive to a port, where an American made crane loads them into an Italian-made ship bound for Sweden. Another German crane and Swedish truck deliver it to the metal refiner, where a Swedish-made plant is used to create a copper-nickel alloy.

A German-made rolling plant then turns the alloy into a thin sheet, shipped in a roll inside a container on a Japanese-made container ship bound for the USA. Eventually after another round of cranes, trains, and trucks, all American this time, it arrives at the company who makes lead frames. They use a Japanese-made machine to stamp the sheet alloy and create the frames themselves. An American-made truck delivers them to the chip foundry.

At a petrochemical plant in China, bulk epoxy resin, plasticisers, pigments, and other products are manufactured. They are supplied in drums, which are shipped on a Chinese-made container ship to an American port where American cranes and trucks do the job of delivering them to an epoxy formulation company. There they are mixed in carefully-selected proportions to produce American-made epoxy semiconductor moulding compound, which is delivered to the chip foundry on an American-made truck.

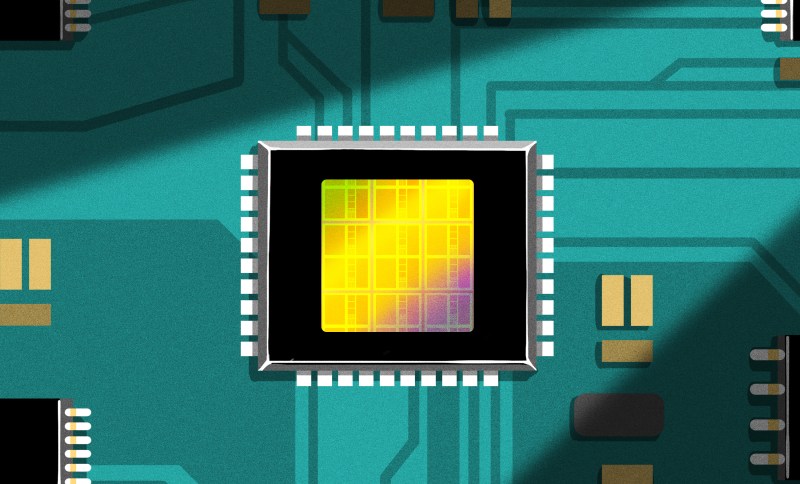

Bringing all Those Countries’ Parts Together

The foundry now has the silicon wafers, lead frames, and epoxy it needs to make an integrated circuit. There are many other chemicals used in its process, but for simplicity we’ll take those three as being the parts which make an IC. What they don’t yet have is an integrated circuit to make. For that there’s a team of high-end engineers in a smart air-conditioned office of an American semiconductor company in California. They are integrated circuit designers, but they don’t design everything. Instead they buy in much of the circuit as intellectual property, which can come from a variety of different countries. Banging the drum as a Brit I’m sure you’ll all know that ARM cores come from Cambridge here in the UK, just to name the most obvious example. So British, German, Dutch, American, and Canadian IP is combined using American software and the knowledge of American engineers, and the resulting design is sent to the foundry.

The process machinery of an integrated circuit foundry lies probably at the most bleeding edge of human technology. The machines this foundry uses are mostly from Eindhoven in the Netherlands, but they are joined by American, German, Japanese, and even British ones. Even then, those machines themselves contain high-precision parts from all those countries and more, so that Dutch machine is also in part American and German too.

Whatever magic the semiconductor foundry does is performed, and at the loading bay appear cartons made from Canadian wood pulp containing reels made from Chinese bulk polymer, that have hundreds of packaged American-made integrated circuits in them. Some of them are shipped on an American truck to an airport, from where they cross the Atlantic in the hold of a pan-European-manufactured jet aircraft to be shipped from the British airport in a German-made truck to an electronics distributor in Northamptonshire. I place an order, and the next day a Polish bloke driving an American-badged van that was made in Turkey delivers a few of them to my door.

The above path from a dusty quarry in Brazil to my front door in Oxfordshire is excessively simplified, and were you to really try to find every possible global contribution it’s likely there would be few countries left out and this document would be hundreds of pages long. I hope mining engineers, metallurgists, chemists, and semiconductor process engineers will forgive me for any omissions or errors. What I hope it does illustrate though is how connected the world of manufacturing is, and how many sources come together to produce a single product. Read’s 1958 pencil is alive and well.

Me as a German didn’t know that Germany is delivering so much cranes into the world. But at leas there is also this little light source which is used for the waver production:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NHSR6AHNiDs

All of which illustrates how an efficient, predictable and well-understood global supply chain can facilitate production, and how capricious tariffs will destabilize established and mature but but doddering national economies.

Our societies only exist because of cooperation. Those who were before us learned and maximized cooperation. Many of today’s leaders and followers, while still standing on other’s shoulders, try to dismount this achievement.

well, it’s not many leaders. I don’t know exactly what the far right leaders in Europe are doing, but this is pretty much just Trump and his sycophants. Billionaires and those who work in finance are trying to capitalize on the volatility to make a quick buck for themselves, but those aren’t exactly “leaders”. Just remember when it all begins to collapse, it was Trump. I could say some things about the American political establishment who let him run and win a second term. Literally, there were many legal reasons to disqualify him, and we failed the country. We failed the world, because we were Trumped.

be sure to advocate against ****ALL**** tariffs and non-tariff trade barriers then. I’m ok with that…but it seems few others have fully normalized their opinions.

Tariffs are the best way to reduce pollution.

We have a lot of ship traffic out there…and it is best that each nation reduce transport through self-sufficiency

Pretty stupid point, unless you wrongly assume all nations are equally large and endowed with same resources. Let USA be self-sufficient in bananas, as “republic”.

“Tariffs are the best way to reduce pollution.”

I thought it was recycling, long term support for products, repairability and reusability of equipment, using biodegradable materials, stop promoting seasonal fashion and cloths made of plastic etc.

“We have a lot of ship traffic out there”

We also have a lot AI generated slop that consumes tons of energy, people flying private jets overseas for shopping or mating, 600+hp sport cars consuming 30+L/Km and rich people arguing we don’t need more trees.

It’s amazing that best way to fix this world is hard work and money of those that have the least ;-)

That’s a perspective error. We have a few hundred supercars, maybe some thousands of luxury vehicles vs. 285 million regular vehicles owned by the general public.

The everyday choices of the common consumer far outweigh the excesses of the rich. They may have the least in terms of money and property, but most in terms of simply consuming stuff, which might have something to do with it.

That’s why stopping the TEMU tsunami is far more effective. Besides, if you complain about one you are really complaining about both.

Tariffs are good and valuable tools to level trade imbalances, but only if judiciously crafted, negotiated and agreed upon by the parties involved.

But wielded capriciously, unilaterally and vindictively they destroy trust and dissuade investment everywhere. It makes it impossible for businesses to plan even just a year out. Factories don’t get built, capital gets squandered, jobs are lost and new ones are not created.

It’s not impossible to plan. Just skip the risk and invest in domestic suppliers. Acting randomly hurts the companies that are sitting on the fence, unable to decide whose side they’re on – the kind of business that would instantly jump back to imports when the tariffs are lifted.

China may be the largest producer of silicon metal, but not for silicon wafers. The grade of the silicon these countries produce is good enough for solar panels and some older semiconductors, not modern CPUs.

The main global source of ultra-high purity silicon is actually in the USA. Without it, the entire semiconductors industry would grind to a halt,

https://www.techspot.com/news/102377-two-mines-north-carolina-key-suppliers-world-semiconductor.html

This is the only place in the world that we’ve discovered, where you can find almost absolutely pure quartz that can make 99.9999999% pure electronic grade silicon. It is of course possible to chemically isolate silicon from other materials, but to do so at the level required for advanced semiconductors is extremely costly.

Silicon a metal?

Metalloid. It depends on who you ask.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metalloid

I went to high school with some of those guys!

Of course the silicon mined in China or Brazil produces impure silicon from the smelting plant, that comes with the territory. I have no idea whether the ore is better in one place than the other or not. But I do know that the silicon from a Brazilian or Chinese smelter can be used as a feedstock for the refiner who produces the wafers, and that refiners produce wafers in many places that aren’t the USA.

Yeah, and the process of refining it is rather nasty. You dissolve it in hot hydrochloric acid to make trichlorosilane and then distill that over and over until you’re left with no impurities. If you’re starting with some random beach sand for quartz, distilling all the other junk out may take a while.

The silane gas is directly useful for making polycrystalline sheets by chemical vapor deposition (Siemens Process), which is why it’s used for making solar panels. However, this process only achieves purity of 99.99999% (seven nines). Getting those last two nines is yet more work, and involves a kind of freeze distillation process where you grow the silicon crystals and then dissolve them again, and then grow them again to push the remaining impurities out. Simply measuring how much other stuff you still have left is difficult at that level, so not a lot of places can do it – at a reasonable cost.

Exactly. I thought most techies found this out when the hurricane came through Pine Spruce, N. Carolina, and coincidentally Youtuber LGR had moved to the area(maybe the guardian spirits of Pure Silicon were calling to him?) in my YT feed less than a week ago popped up: “Saudi Arabia Has Oil, America Has This” from Maxinomics. Thank you for the full explanation.

Chinese silicon chip wafer production currently sits at around 50% of domestic consumption and 15% of world consumption. They seem to be advancing at about 5% per year, probably because theirs are 2/3rds the price …

Thomas L. Friedman’s The World Is Flat (2005)

Thomas L. Friedman’s My Wife Has a Buttload of Money and My View of the Word Has Been Skewed for Decades (ongoing)

“What I hope it does illustrate though is how connected the world of manufacturing is”

I think you did a great job :-)

Simplified it enough that everyone should get the basic idea – even some of the (at least a bit more intelligent) leaders (if there are any).

This article is rubbish, you didn’t specify from where the materials to make the trucks/cranes/ships was sourced and refined, where the clothing adorning the laborers was manufactured, where the food nourishing said laborers was grown, and where the fertilizer used to grow said food was manufactured, etc…

I kid of course :) I remember reading the original I, Pencil, in a freshman-level Econ course, and the world has only become more interconnected since it was written. Well done in bringing the concepts into the nerdier realm!

So it turns out everything is Planet Earth First and America First couldn’t be more wrong.

I think we read different articles. I say America First, for Americans Canada First for Canadians, etc. basically it should be local first. Every country should be as self sustaining as possible.

This article (and Covid) just shows that a supply disruption in one part of the world can cause chaos worldwide in this worldwide supply chain. If each country is as minimally reliant on others as possible, then such disruptions have minimal effect. No country is likely to be 100% self supporting, but you can have only a few items here and there that you need from other countries and be far less open to outside influence.

There is no self-sustaining possible in a modern world unless we go pre-industrial, simple as that. Even in antique times, world trade was a key for development.

Everything’s a trade-off, in life as in engineering. The goal of minimal reliance on other countries comes at a very high cost of duplicating infrastructure across the planet and doing tasks we’re less suited to than the lowest-cost producers. This means a conscious choice to forgo wealth and standard of living to gain security against supply chain risk.

Not a lot of people struggling to make ends meet will find that sacrifice acceptable, especially when the risk is abstract and occasional.

At best there’s a good argument for on-shoring things that can be done efficiently, possibly with increased automation, though even this would have adverse consequences for overall world wealth and stability, and would not be optimum, either.

A stable geopolitical order with interdependence is just fine. The real problem is the stable geopolitical order part of that equation, not the interdependence.

I don’t disagree that the world sets up a large trade network at all, but many points in this feel forced….nor sure if its because of cunninghams law, poe’s law, or something in between. Either way it probably missed the point that should have been made to the twit assuming chips are all USA based, and that is that chip DESIGNING has become commonidty to the point where China can do it. It means service based economies need to find new high skill products if they want to keep their edge. At the same time, this is a warning on becoming a service only based economy. Eventually your services will become commodity, so its foolish to abandon manufacturing. Its foolish to abandon raw material production. Its foolish to completly outsource everything. That doesn’t mean you can’t buy products/raw materials from places that are better at it, just that its foolish to switch to service only.

It’s also foolish to abandon basic education for your citizens.

A society that employs a multitude of manufacturers becomes rich, because the manufacturer does not really cost you anything: they replace their wages with the value they produce.

A society that employs a multitude of servants becomes poor, because servants don’t replace their wages with new value: they merely help you consume more of it for extra cost.

It would be rather more useful that people did nothing instead of establishing a service economy in the lack of manufacturing jobs. If you really don’t need them to work in the mines or the factories, or to do whatever necessary bureaucracy, it would actually be more prudent to pay people to stay home and sit still. At least they wouldn’t waste so much resources coming up with different make-work excuses to get paid.

To understand the point, consider: when people find themselves without gainful employment, what’s the most common thing they do?

They set up a restaurant.

The restaurant will then import expensive ingredients and spices that aren’t locally available, they will load the food up with salt and sugar and fat, to make it taste better than the cheaper healthier home cooked dinner, to entice people to eat there. They will oversize the portions to sell more. They will hire entertainers, musical performances, advertising, they will pay taxes and rents to landlords. They will add to the cost of the food the wages of the staff and the running of the establishment, and good profit for themselves, and tips to the waiters.

And what did we get out of it? Basically nothing. For what little entertainment we gained from a fancy dinner or some convenient fast food, we lost from our pockets the ability to invest in something that returns the value back with surplus. It went to a bunch of jokers whose fundamental point in all of this was to make us pay more for food, so they can have some too.

Why did we ever fall for the trick?

I mean, it’s alright to have a bit of fun and waste sometimes, but when the party becomes a point onto itself, because a very large portion of the people are making their living by keeping the party going, and escalating it constantly, the whole thing actually becomes a tragedy.

It’s like one of those well pumps that charities install in poor African villages. One clever idiot thought to install a carousel to drive the pump, so the children must play in order to get their daily water from it. If not the children, the adults will have to do it. Day after day, week after week, month after month, you must spin the carousel until you’re dizzy to pump the water.

That’s not fun anymore.

Are you upset because children are forced to play or because people have to make effort? Will you be my new lala no effort daddy?

Of gosh. Let me guess where you are from…

“The restaurant will then import expensive ingredients and spices that aren’t locally available, they will load the food up with salt and sugar and fat, to make it taste better than the cheaper healthier home cooked dinner, to entice people to eat there. They will oversize the portions to sell more. They will hire entertainers, musical performances, advertising, they will pay taxes and rents to landlords. They will add to the cost of the food the wages of the staff and the running of the establishment, and good profit for themselves, and tips to the waiters.

And what did we get out of it? Basically nothing.”

Well do I remember the first night the restaurant people came to my house and raped and killed my family to ensure my continued patronage. You don’t want to know what happened the second night when they came back after raping and killing my family, but you can bet I was all restaurant all the time after that!

If you liked “I, Pencil” you’ll love Henry Petroski’s “The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance”. All 448 pages of it.

USA! USA!

This fills me with deep concern. In 1936, the Germans had the same attitude in the hope of solving their social problems. The result was World War II.

Nitpick: ASML is located in Veldhoven, which is almost a suburb of Eindhoven, but stil a separate city.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veldhoven

You have succeeded in making me want to support additive manufacturing R&D….

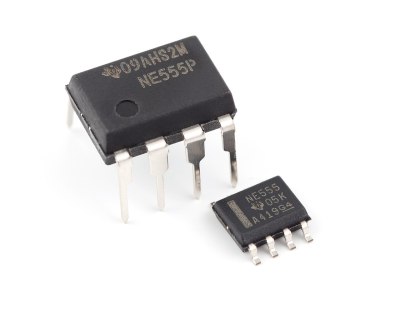

I’ve worked in semicon for almost ten years (we make 555s if you want a hint) and its always amazed me how we can get a wafer from an ingot (from Brazil apparently), process it at a US fab, ship it to SE Asia for packaging, then to China for assembly into a product, and then back to the US in your phone or whatever and the whole operation is still profitable

100% made-in-the-USA projections of $3k smartphones always felt a little low to me

That’s brilliant!