Probably not too many people around the world celebrated November 1st, 2023, but on this momentous date FreeBSD celebrated its 30th birthday. As the first original fork of the first complete and open source Unix operating system (386BSD) it continues the legacy that the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) began in 1978 until its final release in 1995. The related NetBSD project saw its beginnings somewhat later after this as well, also forking from 386BSD. NetBSD saw its first release a few months before FreeBSD’s initial release, but has always followed a different path towards maximum portability unlike the more generic nature of FreeBSD which – per the FAQ – seeks to specialize on a limited number of platforms, while providing the widest range of features on these platforms.

This means that FreeBSD is equally suitable for servers and workstations as for desktops and embedded applications, but each platform gets its own support tier level, with the upcoming version 15.x release only providing first tier support for x86_64 and AArch64 (ARMv8). That said, if you happen to be a billion-dollar company like Sony, you are more than welcome to provide your own FreeBSD support. Sony’s Playstation 3, Playstation 4 and Playstation 5 game consoles namely all run FreeBSD, along with a range of popular networking and NAS platforms from other big names. Clearly, it’s hard to argue with FreeBSD’s popularity.

Despite this, you rarely hear people mention that they are running FreeBSD, unlike Linux, so one might wonder whether there is anything keeping FreeBSD from stretching its digital legs on people’s daily driver desktop systems?

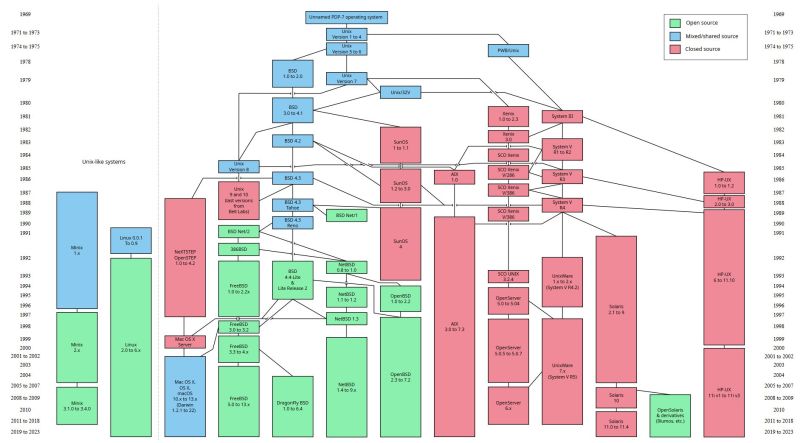

In The Beginning There Was UNIX

Once immortalized on the silver screen with the enthusiastically spoken words “It’s a UNIX system. I know this.”, the Unix operating system (trademarked as UNIX) originated at Bell Labs where it initially was only intended for internal use to make writing and running code for systems like the PDP-11 easier. Widespread external use started with Version 6, but even before that it was the starting point for what came to be known as the Unix-based OSes:

After FreeBSD and NetBSD forked off the 386BSD codebase, both would spawn a few more forks, most notable being OpenBSD which was forked off NetBSD by Theo de Raadt when he was (controversially) removed from the project. From FreeBSD forked the Dragonfly BSD project, while FreeBSD is mostly used directly for specific applications, such as GhostBSD providing a pleasant desktop experience with preconfigured desktop and similar amenities, and pfSense for firewall and router applications. Apple’s Darwin that underlies OS X and later contains a significant amount of FreeBSD code as well.

Overall, FreeBSD is the most commonly used of these OSS BSDs and also the one you’re most likely to think of when considering using a BSD, other than OS X/MacOS, on a desktop system.

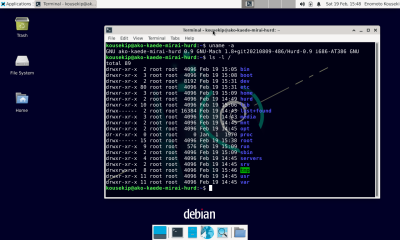

Why FreeBSD Isn’t Linux

The Linux kernel is described as ‘Unix-like’, as much like Minix it does not directly derive from any Unix or BSD but does provide some level of compatibility. A Unix OS meanwhile is the entirety of the tools and applications (‘userland’) that accompany it, something which is provided for Linux-based distributions most commonly from the GNU (‘GNU is Not Unix’) project, ergo these Linux distributions are referred to as GNU/Linux-based to denote their use of the Linux kernel and a GNU userland. There is also a version of Debian which uses GNU userland and the FreeBSD kernel, called Debian GNU/kFreeBSD, alongside a (also Unix-like) Hurd kernel-based flavor of Debian (Debian GNU/Hurd).

In terms of overall identity it’s thus much more appropriate to refer to ‘Linux kernel’ and ‘GNU userland’ features in the context of GNU/Linux, which contrasts with the BSD userland that one finds in the BSDs, including modern-day MacOS. It is this identity of kernel- and userland that most strongly distinguishes these various operating systems and individual distributions.

These differences result in a number of distinguishing features, such as the kernel-level FreeBSD jail feature that can virtualize a single system into multiple independent ones with very little overhead. This is significantly more secure than a filesystem-level chroot jail, which was what Unix originally came with. For other types of virtualization, FreeBSD offers bhyve, which can be contrasted with the kernel-based virtualization machine (KVM) in the Linux kernel. Both of these are hypervisor/virtual machine managers that can run a variety of guest OSes. As demonstrated in a comparison by Jim Salter, between bhyve and KVM there is significant performance difference, with bhyve/NVMe on FreeBSD 13.1 outperforming KVM/VirtIO on Ubuntu 22.04 LTS by a large margin.

What this demonstrates is why FreeBSD for storage and server solutions is such a popular choice, and likely why Sony picked FreeBSD for its customized Playstation operating systems, as these gaming consoles rely heavily on virtualization, as with e.g. the PS5 hypervisor.

OpenZFS And NAS Things

A really popular application of FreeBSD is in Network-Attached Storage (NAS), with originally FreeNAS (now TrueNAS) running the roost here, with iXsystems providing both development and commercial support. Here we saw some recent backlash, as iXsystems announced that they will be adding a GNU/Linux-based solution (TrueNAS SCALE), while the FreeBSD-based version (TrueNAS CORE) will remain stuck on FreeBSD version 13. Here The Register confirmed with iXsystems that this effectively would end TrueNAS on FreeBSD. Which wouldn’t be so bad if performance on Linux wasn’t noticeably worse as covered earlier, and if OpenZFS on Linux wasn’t so problematic.

Unlike with FreeBSD where the ZFS filesystem is an integral part of the kernel, ZFS on Linux is more of an afterthought, with a range of different implementations that each have their own issues, impacting performance and stability. This means that TrueNAS on Linux will be less stable, slower and also use more RAM. Fortunately, as befits an open source ecosystem, an alternative exists in the form of XigmaNAS which was forked from FreeNAS and follows current FreeBSD fairly closely.

So what is the big deal with ZFS? Originally developed by Sun for the Solaris OS, it was released under the open source CDDL license and is the default filesystem for FreeBSD. Unlike most other filesystems, it is both the filesystem and volume manager, which is why it natively handles features such as RAID, snapshots and replication. This also provides it with the ‘self-healing’ ability where some degree of data corruption is detected and corrected, without the need for dedicated RAID controllers or ECC RAM.

For anyone who has had grief with any of the Ext*, Reiserfs or other filesystems (journaled or not) on Linux, this probably sounds pretty good, and its tight integration into FreeBSD again explains why it’s it’s such a popular choice for situations where data integrity, performance and stability are essential.

FreeBSD As A Desktop

It’s probably little surprise that FreeBSD-as-a-desktop is almost boringly similar to GNU/Linux-as-a-desktop, running the Xorg server and one’s desktop environment (DE) of choice. Which also means that it can be frustratingly broken, as I found out while trying to follow the instructions in the FreeBSD handbook for setting up Xfce. This worked about as well as my various attempts over the years to get to a working startx on Debian and Arch. Fortunately trying out another guide on the FreeBSD Foundation site quickly got me on the right path. This is where using GhostBSD (using the Mate DE by default) is a timesaver if you want to use a GUI with your FreeBSD but would like to skip the ‘deciphering startx error messages’ part.

After installation of FreeBSD (with Xfce) or GhostBSD, it’s pretty much your typical desktop experience. You got effectively the same software as on a GNU/Linux distro, with FreeBSD even providing binary (user-space) compatibility with Linux and with official GPU driver support from e.g. NVidia (for x86_64). If you intend to stick to the desktop experience, it’s probably quite unremarkable from here onwards, minus the use of the FreeBSD pkg (and source code ports) package manager instead of apt, pacman, etc.

Doing Some Software Porting

One of my standard ways to test out an operating system is to try and making some of my personal open source projects run on it, particularly NymphCast as it takes me pretty deep through the bowels of the OS and its package management system. Since NymphCast already runs on Linux, this should be a snap, one would think. As it turns out, this was mostly correct. From having had a play with this on FreeBSD a few years ago I was already aware of a few gotchas, such as the difference between GNU make and BSD make, with the former being available as the gmake package and command.

Another thing you may want to do is set up sudo (also a package) as this is not installed by default. After this it took me a few seconds to nail down the names of the dependencies to install via the FreeBSD Ports site, which I added to the NymphCast dependencies shell script. After this I was almost home-free, except for some details.

These details being that on GhostBSD you need to install the GhostBSD*-dev packages to do any development work, and after some consulting with the fine folks over at the #freebsd channel on Libera IRC I concluded that using Clang (the system default) to compile everything instead of GCC would resolve the quaint linker errors, as both apparently link against different c++ libraries (clang/libc++ vs gcc/libstdc++).

This did indeed resolve the last issues, and I had the latest nightly of NymphCast running on FreeBSD 14.1-RELEASE, playing back some videos streaming from Windows & Android systems. Not that this was shocking, as the current stable version is already up on Ports, but that package’s maintainer had make similar tweaks (gmake and use of clang++) as I did, so this should make their work easier for next time.

FreeBSD Is Here To Stay

I’ll be the first to admit that none of the BSDs really were much of a blip on my radar for much of the time that I was spending time with various OSes. Of course, I got lured into GNU/Linux with the vapid declarations of the ‘Year of the Linux Desktop’ back in the late 90s, but FreeBSD seems to always have been ‘that thing for servers’. It might have been just my fascination with porting projects like NymphCast to other platforms that got me started with FreeBSD a few years ago, but the more you look into what it can do and its differences with other OSes, the more you begin to appreciate how it’s a whole, well-rounded package.

At one point in time I made the terrible mistake of reading the ‘Linux From Scratch’ guide, which just reinforced how harrowingly pieced together Linux distributions are. Compared to the singular code bases of the BSDs, it’s almost a miracle that Linux distributions work as well as they do. Another nice thing about FreeBSD is the project structure, with no ‘Czar for life’, but rather a democratically elected core leadership. In the 30-year anniversary reflection article (PDF) in FreeBSD Journal the way this system was created is described. One could say that this creates a merit-based system that rewards even newcomers to the project. As a possible disadvantage, however, it does not create nearly the same clickbait-worthy headlines as another Linus Torvalds rant.

With widespread industry usage of FreeBSD and a strong hobbyist/enthusiast core, it seems fair to say that FreeBSD’s future looks brighter than ever. With FreeBSD available for easy installation on a range of SBCs and running well in a virtual machine, it’s definitely worth it to give it a try.

Running XigmaNAS on a potato NAS.

Edit: one thing I liked about FreeBSD back in the early internet days was the big honking phone book of documentation. Linux back then didn’t quite have that.

After FreeBSD, Linux seems like a chatterbox. Not logical and not consistent, Linux is your bro only until you have no problems.

Tell me about it. In 2019 I installed Ubuntu 18.04 LTS on a second SSD to… well… have a Linux distro for doing “programming stuff”. As time went on it turned out that VirtualBox is really good enough on a 9900K and 64 gigabytes of RAM so in total this Ubuntu install was used maybe for 30 hours total.

In 2023 I finally booted to it again, did

apt updateandapt upgrade. After doing the upgrade it faled to start as long as my Logitech G603 mouse was plugged in. I tried to fix it, but after reading plenty of blah-blah-blah-whocares technical kernel mumble-jumble I just decided to simply boot back to Windows 10 again.One day I’ll probaby recover those few files I keep there and format the SSD, but for now I don’t care.

I didn’t update my OS for 4 years, tried nothing and it didn’t work, Linux is hard.

Part of using a computer is taking responsibility for it’s upkeep and maintenance, which is why Microsoft has to treat their users like children and force them to stay updated.

With VirtualBox it is possible to boot e.g. an existing GNU/Linux installation from the actual hardware.

Basically a dualboot system where you can boot the same Linux from inside Windows.

Dunno what exactly needs to be done for/with/in Linux to make it possible but VB basically just needs “written permission” to directly access the Linux partitions on your storage drive.

Open source, ei no planning ahead.

Agree!

What’s the air like, all the way up on that high horse?

Known advantage of horse back riding is having overview over the crowd. Over here has riot police many horses.

It is a bit thin, but clouds don’t block my view of aurorae and I can see the curvature of the Earth.

Double plus good.

You’re the one who came to an open source OS thread with no epic mount. BSD implies at least a +1 Horse of Ostentatious Virtues, so you can look down on the regular Ubuntu using high horses. :D

Sony and every other commercial entity above chose BSD for the license. These companies are parasitic and do not want to give anything back to the free/libre software projects that made their products possible. The Linux kernel is GPL2 which allows you to freely use it for anything, but if you make improvements, you have to give them back to the greater community.

I’m glad the BSDs exist, and have used them, in the past. But, for commercial entities there is usually only one reason for choosing BSD– the BSD license allows corporate parasitism.

How it parasitism when the authors decided that anyone can use their software as they see fit?

your choice not to kill worm in your internals does not mean it is not parasitic :)

And yet it continues “in spite of” the license. Maybe cluing us in the fact that the license isn’t the impediment the other side of the aisle makes it out to be.

parasitism is just a special case of symbiosis. there’s reason to chose many relationships but i wouldn’t denigrate bsd for being a popular starting point for commercial forks, and i wouldn’t denigrate profitable ventures for using appropriately-licensed freely-available source.

i think this is one of those cases where i want to remove the word “just” from sentences. like: a lot of for-profit value-add is just bundling and wrapping and window-dressing and even gate-keeping. those things are not valueless.

i know i’m not alone in the joy of sharing my software without concern for whether the next guy wants to share his software.

What a downright unfortunate and warped perspective you have.

I’ve contributed to MAME – an open-source arcade (and now more or less “everything”) emulator since around 2001, four years after the project’s inception. From the get-go, it had a custom license, specifically prohibiting the project’s codebase from being “used commercially”.

Somehow, bizarrely, these random words written by a dude from Italy carried literally zero weight and were utterly unenforceable against the legions of folks from Shenzhou (or wherever) who almost immediately started filing the proverbial VINs off the codebase and shipping it, alongside copies of classic ROM sets, on cheap arcade-compatible boards powered by a 200MHz ARM SoC (the PXA255). Incidentally, MAME now actually emulates some of those bootlegs (albeit slowly).

You know who actually did follow that “no commercial use” clause? Museums. Well-meaning organizations. People who actually wanted to keep the spark of arcades alive more or less had their hands tied. Rather than reaching out for an exemption, many organizations opted instead to eschew emulated versions of their legacy articles entirely, diminishing the effort to preserve these systems overall.

You speak brashly and confidently but without reason. As if some license will magically prevent bad actors from taking advantage of open-source projects. Here in the real world, a license is only worth as much as you’re willing to put into defending it legally.

Don’t bring up the FSF, because been there, done that. The FSF picks and chooses with enormous discretion which GPL violations they will litigate. Hint, it’s usually projects that have some novelty to the lawsuit, or which will otherwise be a proverbial feather in their caps. For the most part, smaller projects, emulators especially, are more or less left to twist as they’re pillaged for everything they’re worth by people who don’t care about licenses in the first place.

So, why am I bringing this up in an article about BSD? It’s because back in 2015, the project was relicensed to exist under FOSS-recognized licenses, with no customization. After contacting every single contributor from the prior 18 years of the project’s existence (only two were unaccounted for, and the small amount of their code was subsequently removed), core files are now licensed under either MIT or 3-clause BSD, with the full knowledge that companies will be able to use the codebase commercially.

What has this led to? Well, for one thing, game companies that are interested in shipping software that has the best possible emulation quality on a PC (FPGA solutions like MiSTer are still the top of the pops for overall accuracy) have an easy, go-to solution. All they’re required to do is give the necessary legal acknowledgement in the software documentation itself. Capcom, for example, did this in Capcom Arcade Stadium Volume 2.

As for the bad actors, malicious competitors, and people who regularly spit on FOSS? Well, they’re still out there, and they’re still going to keep doing it.

But get over yourself. You don’t need to white-knight the honor of these FOSS projects like you seem to think in your head you’re doing. These projects are led by people, who have their own personal agency, and tend to choose BSD with the full knowledge of the commercial-use aspect. If they don’t consider it parasitic, then it’s not your position to claim that it is.

It’s not clear to me that Sony chose BSD for PS4/PS5 because of the license, as they use Linux in lots of their products, and don’t seem to have an issue sharing their changes/improvements: https://oss.sony.net/Products/Linux/common/search.html

NetBSD started before FreeBSD. Did 0.8 and 0.9 releases months earlier, which were very stable, and 1.0 on Nov 8th. One week after FreeBSD’s 1.0

Yes that’s a crucial fact the author’s missed altogether. BSDNet (can’t remember it’s public name) was running concurrently with 386BSD until the governing board directive to discontinue distributing AT&T infected code.

There was not two. AT&T free code bases that week. Net was major releasing 1.0 for all it’s architectures whereas the impatient 386’s forked and ran by themselves a week early ostensibly to catch LINUX (heh heh, with loftier edge bleed goals).

So their baseline could not have been anything but NetBSD 0.9. Later the same thing happened where founding member DeRaadt got kicked out. He shamelessly forked NetBSD into OpenBSD.

Anyone who thinks otherwise can go check the very first commit infrastructure of Net and Free for the fingerprints of one irrepressible Theo de Raadt in their birth unbilical chords.

FreeBSD prioritising laptops could well be a turning point. As someone who moves from FreeBSD to nearly random Linux distros since.

I can say that categorically the single main reason was that Linux “just works” usually more often than Windows. FreeBSD doesn’t.

A low hanging fruit is getting acceleration going for VMs running fbsd. If you can get vm-tools working well why would anyone trust you to get a random laptop working well?

“I don’t know why the playstation 4 and 5 are mentioned. After sony (no capital there from me) removed the OtherOS from the playstation 3 in 2010 I lost any interest in that company.”

Exactly! Who cares if people do things differently than you, you’re the authority on what’s right and wrong because only YOUR opinion matters.

SMDH…

I think this would be better stated as was, not is – GNU/kFreeBSD was discontinued in Debian 8, and as of around Bookworm (Debian 12)’s release, GNU/kFreeBSD’s status was updated to ‘terminated’, due to a lack of maintainer interest.

Factually incorrect. Stability and RAM usage are virtually identical in both environments. Speed varies with some workloads faster on BSD, and others faster on Linux. Over time this will tip over to Linux being the most optimized for speed in nearly all use-cases.

Just saying…

https://hackaday.com/2023/08/01/jennys-daily-drivers-freebsd-13-2/

(Thanks Jenny)

I used FreeBSD on-and-off (having started my PC *ix experience with 386BSD 0.0). It’s a good system. Installing has improved, but is still messier than Linux. For the most part, though, it’s simple, clean, and elegant. As an OS should be.

FreeBSD is generally as fast, or faster, than Linux, except on wireless networking, where Linux blows the socks off FreeBSD.

It is my impression that one steers towards Linux for a rich feature set, wider driver support, wider platform support, and cutting-edge OS innovations, but towards FreeBSD for maximum exploitable horsepower and maximum stability. But I’m open to contradiction on that impression.

There are other OS’ that are worthy of examination (Haiku, 9Front, and OpenIndiana, for example), but the first of these is incomplete and the other two can’t compete against a pre-existing user base.

It’s fun to imagine how things might have been, had all five of these OS’ appeared in 1993 with the first 32-bit CPUs and long before Microsoft could do preemptive multitasking.

Although I consider myself a Linux guy, I’m also a very happy user of XigmaNAS installed on a Mini PC with external USB3 8×3.5 drive bay arranged as 4 ZFS pools, then a OpnSense firewall installed on a dedicated multi Ethernet appliance; both FreeBSD based. They simply rock; you turn them on and save for needed updates you never need for reboots.

Nice original artwork headlining this article!

Ahhh, fragmentation, scourge of adoption. How many different forks and splinters of the same basic thing were mentioned in this article? I lost count.

I find it a bit unfair not to mention LXC (Linux containers) as more closer counterpart to BSD jails, rather than the full-blown KVM to which you compared it instead.

From Paolo Del Bene, 29 Oct 2024 at 01:00 p.m. Gnu/linux is not only a question of an appropriate 100% Free Software operating system, but actually we do not have Hardware 100% Free, infact much hardware uses NON free bios and it is interested the possibility to install 100% Free Software and those operating systems that are open source and that have nothing in common with Free Software because the Initial Announcement of Free Software was published 27 Sept 1983 while open source was released in 1991.

I love the family tree graphic.

There appear to be a bunch of workstation unixes missing – similar to Sun and HP, like DEC, Apollo and SGI. I know there were ports of BSD for DEC as I used it in the ’80s on Vaxstations at Berkeley. I don’t know the origin of the commercial version I used a decade later.

There’s also probably an offshoot for embedded/mobile/RTOS unixes that aren’t based on Linux.

I Paolo Del Bene, 30 Oct 2024 at 05:51 a.m. i am NOT interested to use operating systems that are NON free software, i am interested to use operating systems 100% Free Software as the Gnu/linux distributions published here https://www.gnu.org/distros/free-distros.html#for-pc and i am interested to operating system Gnu/Hurd https://www.gnu.org/software/hurd/ anyway the hardware must be Free to grant FreeDom to the users and Not that Shit of NON free hardware! Best Regards, Paolo Del Bene

This is why we pour our coffee BEFORE we post.

Have a nice day!

My poop-free NVIDIA GK107GLM (Quadro K1100M) and the port of NVIDIA’s driver wish to convey their best regards to your Del Bene.

“…one might wonder whether there is anything keeping FreeBSD from stretching its digital legs on people’s daily driver desktop systems…”

I installed it for a short while on my old laptop some time ago

My initial impression was pretty good. It was fast. I normally use Linux for a desktop at home so it seemed to be pretty much the same software I was used to but faster and less bloated. It was kind of like going back in time 10 years in all the good ways but still being up to date in all the ways where that is good.

Except one…

I wanted to watch Netflix and Hulu. Yah, sure, I can disagree with DRM philosophically. But that doesn’t put the show I want to watch on the screen now does it? So it was a nice experiment but back to Linux.

Install www/foreign-cdm and www/linux-widevine-cdm, then enjoy Widevine-protected content Chromium on FreeBSD.

https://www.freshports.org/www/foreign-cdm/

https://www.freshports.org/www/linux-widevine-cdm/

Seek help in Reddit, if you like.

Thanks! Boosted:

https://old.reddit.com/r/freebsd/comments/1gsju0j/freebsd_at_30_the_history_and_future_of_the_most/

Correction: the thirtieth anniversary was in June, not November, 2023.

https://freebsdfoundation.org/blog/celebrating-30-years-of-freebsd-freebsd-timeline/

https://freebsdfoundation.org/blog/celebrating-30-years-of-freebsd-freebsd-journal-special-edition/