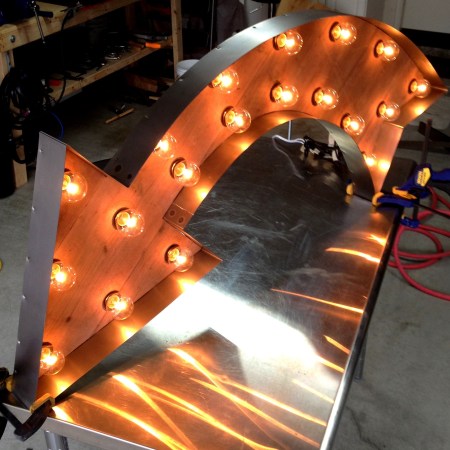

[Gnsart] builds props often used in the film industry. He’s created an amazing retro Vegas style light chaser sign. The sign was started as a job a few years ago. While [Gnsart] could handle the physical assembly, the cost of a mechanical light chaser pushed the project over budget. The sign project was cancelled back then, but he never forgot it.

Fast forward to a few weeks ago. [Gnsart] happened upon the Arduino community. He realized that with an Arduino Uno and a commonly available relay board, he could finally build the sign. He started with some leftover cedar fence pickets. The pickets were glued up and then cut into an arrow shape. The holes for the lights were then laid out and drilled with a paddle bit. [Gnsart] wanted the wood to look a bit aged, so he created an ebonizing stain. 0000 steel wool, submerged and allowed to rust in vinegar for a few days, created a liquid which was perfect for the task. The solution is brushed on and removed just like stain, resulting in an aged wood. We’ve seen this technique used before with tea, stain, and other materials to achieve the desired effect.

[Gnsart] then built his edging. 22 gauge steel sheet metal was bent to fit the outline in a bending brake. The steel sheet was stapled to the wood, then spot welded to create one continuous piece. Finally, the light sockets were installed and wired up to the Arduino. [Gnsart] first experimented with mechanical relays, and while we love the sound, we’re not sure how long they’d last. He wisely decided to go with solid state relays for the final implementation. The result speaks for itself. LEDs are great – but there is just something about the warm glow of low-wattage incandescent lights.