The basic principles of a motion picture film camera should be well understood by most readers — after all, it’s been well over a hundred years since the Lumière brothers wowed 19th century Paris with their first films. But making one yourself is another matter entirely, as they are surprisingly complex and high-precision devices. This hasn’t stopped [Henry Kidman] from giving it a go though, and what makes his camera more remarkable is that it’s 3D printed.

The problem facing a 16mm movie camera designer lies in precisely advancing the film by one frame at the correct rate while filming, something done in the past with a small metal claw that grabs each successive sprocket. His design eschews that for a sprocket driven by a stepper motor from an Arduino. His rotary shutter is driven by another stepper motor, and he has the basis of a good camera.

The tests show promise, but he encounters a stability problem, because as it turns out, it’s difficult to print a 16mm sprocket in plastic without it warping. He solves this by aligning frames in post-processing. After fixing a range of small problems though, he has a camera that delivers a very good picture quality, and that makes us envious.

Sadly, those of us who ply our film-hacking craft in 8mm don’t have the luxury of enough space for a sprocket to replace the claw.

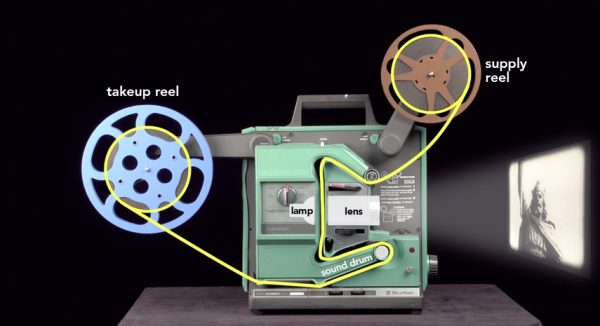

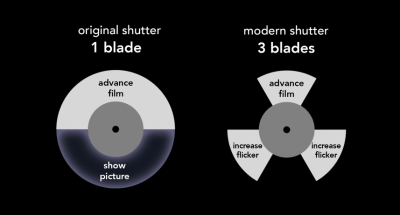

Film is projected at a rate of 24 frames per second, which is sufficient to create the POV illusion. A projector’s shutter inserts itself between the lamp and the lens, blocking the light to prevent projection of the film’s physical movement. But these short periods of darkness, or flicker, present a problem. Originally, shutters were made in the shape of a semi-circle, so they block the light half of the time. Someone figured out that increasing the flicker rate to 60-70 times per second would have the effect of constant brightness. And so the modern shutter has three blades: one blocks projection of the film’s movement, and the other two simply increase flicker.

Film is projected at a rate of 24 frames per second, which is sufficient to create the POV illusion. A projector’s shutter inserts itself between the lamp and the lens, blocking the light to prevent projection of the film’s physical movement. But these short periods of darkness, or flicker, present a problem. Originally, shutters were made in the shape of a semi-circle, so they block the light half of the time. Someone figured out that increasing the flicker rate to 60-70 times per second would have the effect of constant brightness. And so the modern shutter has three blades: one blocks projection of the film’s movement, and the other two simply increase flicker.