Lisp is one of those programming languages that seems to keep taunting us for not learning it properly. It is still used for teaching functional languages today. [Adam McDaniel] has an obvious fondness for this fifty-year-old language and has used it in several projects, including their own shell, Dune.

Dune is a shell designed for powerful scripting. Think of it as an unholy combination of bash and Lisp.

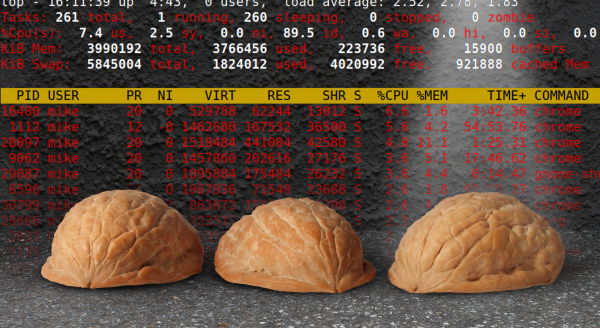

Dune is designed to be highly customisable, allowing you to create a super-optimised workstation for your admin and programming tasks. [Adam] describes the front end for Dune as having turned up the cosiness dial to eleven, and we can see that. A cosy home is personalised, and Dune lets you customise everything.

Dune is a useable functional programming environment with a reasonably complete standard library to back it up, which should simplify some of the more complicated sysadmin tasks. [Adam] says the language also supports a few metaprogramming concepts, such as a quote operator, operator overloading, and macro programming. It’s difficult to describe much more about what you can do with Dune, as it’s a general-purpose programming language wrapped in a shell. The possibilities are endless, and [Adam] is looking forward to seeing what you lot out there do with his project!

The shell can be personalised by editing the prelude file, which allows you to overload functions for the prompt text, the incomplete prompt text (so you can implement intelligent completion options), and a function that deals with the formatting of the command response text. [Adam] gives us his personal prelude file, which defines many helper functions displaying useful things such as the current weather, a calendar, and an ASCII art cat. You never know when that might come in handy. This file is written in Lisp, so we reckon that’s where many people will start as they come up the Lisp (re)learning curve before embarking on more involved automation. Dune was written in Rust, so you need that infrastructure to install it with Cargo.

As we said earlier, Lisp is not a new language. We found a hack for porting a Lisp interpreter to any old language and also running Lisp bare metal on a Lisp machine. Finally, [Al] takes a look at some alternative shells.