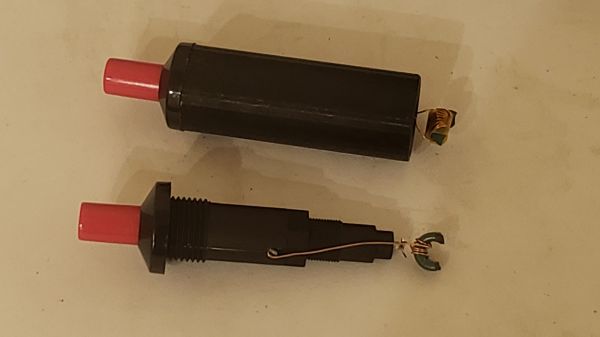

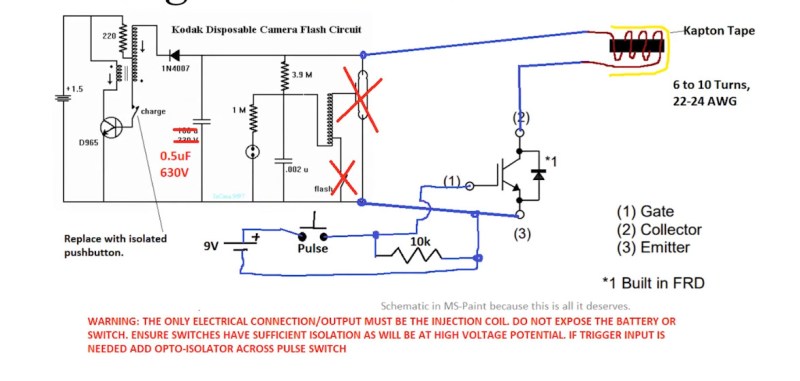

One of the many fascinating fields that’s covered by Hackaday’s remit lies in the world of hardware security, working with physical electronic hardware to reveal inner secrets concealed in its firmware. Colin O’Flynn is the originator of the ChipWhisperer open-source analysis and fault injection board, and he is a master of the art of glitching chips. We were lucky enough to be able to welcome him to speak at last year’s Remoticon on-line conference, and now you can watch the video of his talk below the break. If you need to learn how to break RSA encryption with something like a disposable camera flash, this is the talk for you.

This talk is an introduction to signal sniffing and fault injection techniques. It’s well-presented and not presented as some unattainable wizardry, and as his power analysis demo shows a clearly different trace on the correct first letter of a password attack the viewer is left with an understanding of what’s going on rather than hoping for inspiration in a stream of the incomprehensible. The learning potential of being in full control of both instrument and target is evident, and continues as the talk moves onto fault injection with an introduction to power supply glitching as a technique to influence code execution.

Continue reading “Remoticon 2021 // Colin O’Flynn Zaps Chips (And They Talk)”