There are a lot of ways to try to mathematically quantify how healthy a person is. Things like resting pulse rate, blood pressure, and blood oxygenation are all quite simple to measure and can be used to predict various clinical outcomes. However, one you may not have considered is gait velocity, or the speed at which a person walks. It turns out gait velocity is a viable way to predict the onset of a wide variety of conditions, such as congestive heart failure or chronic obtrusive pulmonary disease. It turns out, as people become sick, elderly or infirm, they tend to walk slower – just like the little riflemen in your favourite RTS when their healthbar’s way in the red. But how does one measure this? MIT’s CSAIL has stepped up, with a way to measure walking speed completely wirelessly.

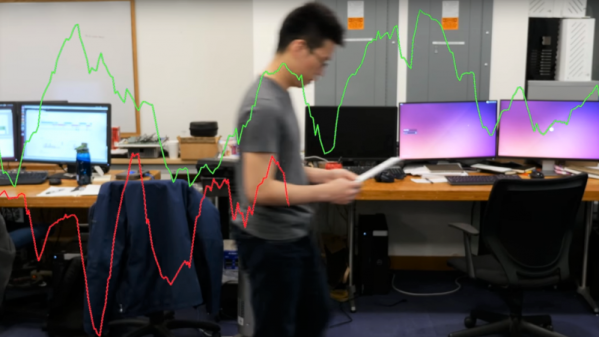

You can read the paper here (PDF). The WiGate device sends out a low-power radio signal, and then measures the reflections to determine a person’s location over time. Alone, however, this is not enough – it’s important to measure the walking speed specifically, to avoid false positives being triggered by a person simply not moving while watching television, for example. Algorithms are used to separate walking activity from the data set, allowing the device to sit in the background, recording walking speed data with no user interaction required whatsoever.

This form of passive monitoring could have great applications in nursing homes, where staff often have a huge number of patients to monitor. It would allow the collection of clinically relevant data without the need for any human intervention; the device could simply alert staff when a patient’s walking pattern is indicative of a bigger problem.

We see some great health research here at Hackaday – like this open source ECG. Video after the break.

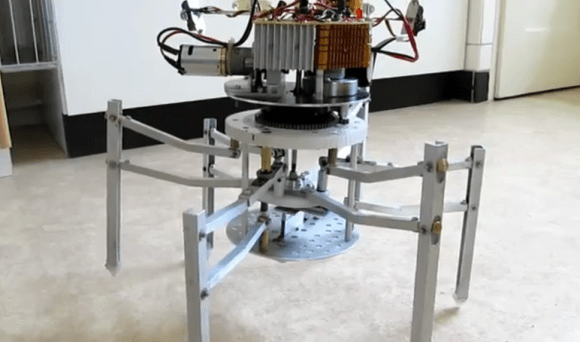

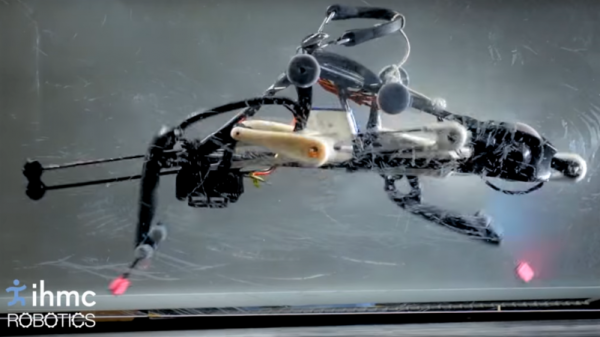

A single motor runs the entire drive chain using linkages that will look familiar to anyone who has taken an elliptical trainer apart, and there’s not a computer or sensor on board. The PER keeps its balance by what the team calls “reactive resilience”: torsion springs between the drive sprocket and cranks automatically modulate the power to both the landing leg and the swing leg to confer stability during a run. The video below shows this well if you single-frame it starting at 2:03; note the variable angles of the crank arms as the robot works through its stride.

A single motor runs the entire drive chain using linkages that will look familiar to anyone who has taken an elliptical trainer apart, and there’s not a computer or sensor on board. The PER keeps its balance by what the team calls “reactive resilience”: torsion springs between the drive sprocket and cranks automatically modulate the power to both the landing leg and the swing leg to confer stability during a run. The video below shows this well if you single-frame it starting at 2:03; note the variable angles of the crank arms as the robot works through its stride.