Our offline password keeper project (aka Mooltipass) is quite lucky to have very active (and very competent) contributors. [Harlequin-tech] recently finished our OLED screen low level graphics library which (among others) supports RLE decompression, variable-width fonts and multiple bit depths for fonts & bitmaps. To make things easy, he also published a nice python script to automatically generate c header files from bitmap pictures and another one to export fonts.

[Miguel] finished the AES encryption/decryption schemes (using AES in CTR mode) and wrote an awesome readme which explains how everything works and how someone may check his code using several standardized tests. We highly encourage readers to make sure that we didn’t make any mistake, as it was one of you that suggested we migrate to CTR mode (thanks [mate]!).

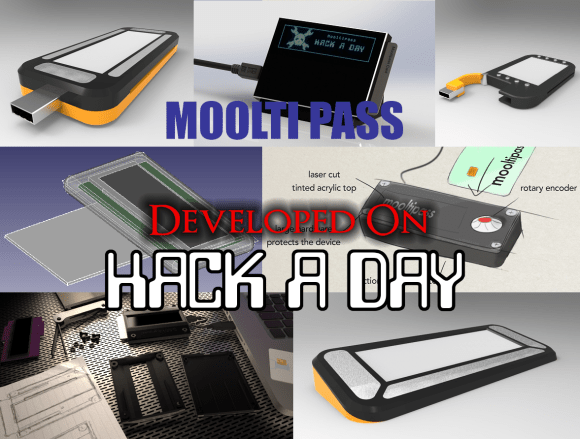

On the hardware side, we launched into production the top & bottom PCBs for Olivier’s design. We’re also currently looking for someone that has many Arduino shields to make sure that they can be connected to the Mooltipass. A few days ago we successfully put the Arduino bootloader inside our microcontroller and made the official Arduino Ethernet shield work with it.

Finally, as you may have guessed from the picture above our dear smart card re-sellers can pretty much print anything on them (these are samples). If one of you is motivated to draw something, please contact me at mathieu[at]hackaday.com!

On a (way) more childish note, don’t hesitate to give a skull to the mooltipass on HaD projects so it may reclaim its rightful spot as “most skulled“.