As a happy side-effect of the smartphone revolution, the world is now awash with tiny computers that are incredibly cheap thanks to the nearly unfathomable volumes in which their components are manufactured. There wouldn’t be a $10 Raspberry Pi Zero if the billions of smartphones that were pumped out before it hadn’t dropped the cost of the individual components to literal pennies. That also means that smartphone hardware, or at least systems that are very close to it, have started to pop up in some unexpected places.

When [Joshua Wise] recently took ownership of a Wahoo ELEMNT BOLT bike computer, he wondered how it worked. With impressive list of features such as Internet connectivity, GPS mapping, and Bluetooth Low Energy support, he reasoned the pocket-sized device must have some pretty decent hardware under the hood. With some poking and prodding he found the device was powered by a MediaTek SoC and incredibly had a full-blown install of Android running in the background.

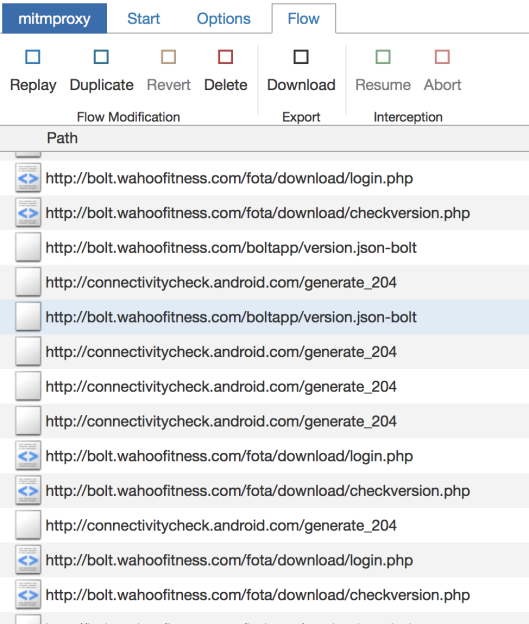

So how does one find out that their lowly bike computer is essentially a cleverly disguised smartphone? If you’re [Joshua], you listen to who it’s trying to talk do when doing a firmware update over the Internet. He used

So how does one find out that their lowly bike computer is essentially a cleverly disguised smartphone? If you’re [Joshua], you listen to who it’s trying to talk do when doing a firmware update over the Internet. He used mitmproxy running between his Internet connection and a WiFi access point setup specifically for the BOLT, from there, he was able to see all of the servers it was connecting to. Seeing the device pull some data down from MediaTek’s servers was a pretty good indication of whose hardware was actually inside the thing, and when it ultimately downloaded some Android .apk files from the Wahoo website, it became pretty clear what operating system it was running underneath the customized user interface.

Further examination of the Bolt’s software brought to light a few troubling issues. It turned out that the firmware made extensive use of Apache-licensed code, for which no attribution was given. [Joshua] contacted the company and was eventually referred to the Wahoo’s CEO, Chip Hawkins. Refreshingly, Chip was not only very interested in getting the licensing issues sorted out, but even had some tips on hacking and modifying the device, including how to enable ADB.

Before the publication of this article, we reached out to Chip Hawkins (yes, he really does respond to emails) for a comment, and he told us that not only has he made sure that all of the open source packages used have now been properly attributed to their original authors, but that his team has been providing source code and information to those who request it. He says that he’s been proud to see owners of his products modifying them for their specific needs, and he’s happy to facilitate that in any way that he can.

Open source license compliance is a big deal in the hacking community, and we’ve seen how being on the wrong side of the GPL can lead to lost sales. It’s good to see Wahoo taking steps to make sure they comply with all applicable licences, but we’re even more impressed with their positive stance on customers exploring and modifying their products. If more companies took such an enlightened approach to hacking, we’d all be a lot better off.

[Thanks to Roman for the tip.]