A bunch of people who share a large workshop and meet on a regular basis to do projects and get some input. A place where kids can learn to build robots instead of becoming robots. A little community-driven factory, or just a lair for hackers. The world needs more of these spaces, and every hackerspace, makerspace or fab lab has its very own way of making it work. Nevertheless, when and if problems and challenges show up – they are always the same – almost stereotypically, so avoid some of the pitfalls and make use of the learnings from almost a decade of makerspacing to get it just right. Let’s take a look at just what it takes to get one of these spaces up and running well.

Choosing A Legal Form

When choosing a legal form for your makerspace – or anything else – you will usually weigh freedoms against the liabilities. Freedoms can be the ability to make profits, or the possibility to hand out tax-deductible donation receipts. Liabilities can arise from taxation or the claim for damages by a third party. Because it excludes the private assets of the founders from the liability of the makerspace as a legal entity, it’s generally considered safer to form the country-specific equivalent of a limited liability company – an LLC – than going completely unincorporated. Most countries – and most US states (except Kentucky, Minnesota, Tennessee) provide tax-exemptions for LLCs with a non-profit purpose. Still, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, and to use your full potential – first – consult your tax consultant and – second – get legal advice from a lawyer, too.

Dealing With Tax And Accounting

Since makerspaces aren’t companies with large numbers of in and outgoing transactions, it’s fair to say that the most basic book-keeping software and a dedicated member will do on the accounting side. However, there’s no point in manually tracking each monthly membership fee payment, so that’s the baseline of functionality you are looking for. At the end of the year, you do good in getting a capable tax consultant to take care of the tax declaration in detail – and in time.

Getting An Insurance

A makerspace needs an insurance, and it’s not necessarily a problem to get one. Yet, some insurance companies will want to inspect the spaces and installations beforehand. This usually creates an insurance gap when you’re just setting up your space, and this is the time when the most accidents happen. Talk to your insurance about this to be insured before and after you open the doors. Also, check the scope of your insurance, and check if it covers only members or also guests of the makerspace.

Setting A Mission Statement

Some see makerspaces as fully fledged prototyping laboratories, where you find all the fancy tools from waterjet cutters to pick-and place machines. To others, this is reserved only to the small community driven factories named fablabs. Another direction turns to makerspaces as purely educational institutions where kids can learn STEM skills and get excited about technology. Or you’re just setting up a repair café. If you want to run a makerspace, there should be clarity about where it’s going.

The numbers

Sooner or later in your planning phase, you may want to open a spreadsheet and get a feel for the numbers, both for the setup and the operational costs.

Turnover

The first sustainable income your makerspace is going to have will most certainly be the membership fee, paid by the founders and the first members of the space. Only add other income sources, such as sponsors, if they are secured and not based on speculations.

Operational Cost

This is what will have to cover the basic, recurring cost, such as rent, insurance, electricity, broadband internet, water and the tax consultant at the end of the year. If nobody in the founding team has considerable experience with bookkeeping, you may want to outsource that as well and allocate a reasonable amount for that.

This is what will have to cover the basic, recurring cost, such as rent, insurance, electricity, broadband internet, water and the tax consultant at the end of the year. If nobody in the founding team has considerable experience with bookkeeping, you may want to outsource that as well and allocate a reasonable amount for that.

Most costs scale with the growth of your space, but first and foremost, it all boils down to the rent. So basically, all you have to do is gather a few reasonable quotes for square meter prices in the area where you want to open your space and figure out the size of the space. This can be done by thinking big and allocating space for the different subsections of a space, or by being economical to see what you can afford from the start and then squeeze everything in that figure.

For the latter option, a reasonable starting point could be a basic minimum of 50 square meters, and for example two square meters of extra space for each member that is expected to join within the first 6 months. At this point, you may already anticipate growth and weigh the cost of paying for extra space now against the cost of relocating later. Usually, relocating is considerably cheaper, although, for a newly started space, the first location should at least allow for a member growth of at least 100%.

The Setup Cost

The setup cost of a makerspace is dominated by the founding cost, mostly state fees and notary cost, the security deposit for the premises, and the cost of making the space usable by and filling it with equipment. The founding team will probably already own equipment to contribute. A few tools here, maybe a small laser cutter or a reflow oven there. That’s good, since it saves you money, and unless you’re running your space as a profitable business with a rock solid business plan, a loan might not be the best start for your makerspace.

You will probably still need a bit of capital to fill your space with more equipment and become operational, and it is a challenge on its own to raise that. If you and the other founders don’t pour in some money, you will need to go on the hunt for sponsors. Either way, these expenses will come with a reasonable planning effort.

Paid Staff

If you still have your spreadsheet open, you may have noticed how the numbers change with more members. When you’re just getting started, it’s all about operating efficiently and self-managed. Once you grow, more membership fees come in, and the higher utilization of space and equipment lower the cost per member. Unfortunately, with higher utilization, the impact of equipment downtimes also goes up. If you are just getting started, you probably don’t even have to think about this, but for makerspaces that already have grown to a certain size, the requirement for dedicated workshop staff may arise. The threshold for this is quite high, yet when reaching about 500 members and 1,000 square meters (about 10,000 square feet) of space area, even the best self-management efforts can lead to chaos.

Equipment

Even if you aren’t about to open a little factory – at the end of the day, projects are born from possibilities. Therefore, equipment is one of the core values a makerspace can offer its members. The acquisition of equipment requires thorough planning to ensure completeness: You don’t need everything, but you need everything to make a project happen.

The First Aid Kit

It’s the first thing you need to get, and it deserves being mentioned first. Every other item can be bought when the need comes up.

Quality And Quantity

The concept of sharing allows you to look for more expensive and higher quality equipment, which will help you tackle the issue of increased wear in a workshop environment. A single industrial grade multimeter is always better than a bucket of broken ones. Yet, neither will enable your members to give a proper electronics workshop with 20 participants. The same is true for soldering irons, screwdrivers, pliers, and many other things.

The Laser Cutter

Laser cutters and makerspaces belong together. These amazing machines are affordable, have a high throughput and low operating cost. Everybody can learn how to use them, and since they are fast and reliable, with rare downtimes, even large spaces usually don’t maintain more than one machine. So what can possibly go wrong? Well, not too much, if you’ve read Donald’s guideline on the topic. Besides the follow-up costs of fume extraction and cooling systems, CO2 laser cutting systems above a certain power level – about 150 Watts – need an oxygen supply to cut metals, which results in higher operating costs.

The 3D Printers

3D-printers and makerspaces belong together, too. But it’s a love-hate relationship. They are easy to use, yet it’s also easy enough to produce failure for people who are new to the toolchain. That is – of course – part of any learning experience, but will inevitably result in downtimes. People will throw the most impossible geometries, G-Code instructions and materials at those machines, and 3D printers aren’t usually smart enough to notice that they are about to break themselves.

Therefore, avoid fancy dual or triple extrusion setups that complicate things even further and go for simple, reliable machines that come with either a proper toolchain or at least some well-tuned presets for open-source toolchains. When you calculate the budget for this section, consider that you will sooner or later need more than one 3D printer because, with growing member count, the low throughput of 3D printers will become a noticeable limitation.

The Rest Of The Machine Park

For commercial makerspaces, it’s typically the way to go for a fully fledged machine park from the start, from the waterjet, 6-axis CNC, press brake and sandblasting chamber, to the TIG welder. The availability of machines accelerates the growth of the member count and quickly compensates for the acquisition costs.

Yet, the force is with NPO makerspaces on this one, and you’d be surprised how much abandoned equipment can be found in the basements of this world. They’re waiting for you to be acquired in exchange for a tax relieving donation receipt or a bucket of corporate-responsibility-karma-points. If possible, approach local manufacturers or resellers directly and ask if they can help you out and you might retrieve an unsellable display item.

Self-Organization

Electronic Door Lock

Because it takes an organizational effort to run your makerspace with opening hours, most makerspace operate as open workshops, with people coming and going whenever they want. While members will carry keys, to everybody else, the doors are closed and locked, protecting the valuable infrastructure from theft, vandalism, and occupation.

However, handing out more and more mechanical keys to a mechanical lock brings a significant administrative effort, it also perforates the security of the door in which the lock resides. Eventually, it becomes obsolete. Mechanical keys can be copied, they can be lost, and they can only be invalidated with the consent of the current holder. Especially in makerspaces, where unusual machinery such as key-cutting-machines is not unusual at all, mechanical keys are useless.

An electronic door lock based on contactless smart cards or tags is the way to go here, and in many large makerspaces, this is already a reality. Unlike mechanical keys, contactless smart cards offer protection against cloning. Similar solutions based on NFC or other RFID tags don’t have this cloning protection, but at least they can be tracked and invalidated if they are lost or otherwise compromised. All of them are cheap to acquire in quantities and can be used around the space in many ways, one of them being machine access control. A great example implementation of an NFC-based system is the Milwaukee Makerspace Access Control System. In addition to that, if your makerspace is rather large and has more than one doors, it’s a good idea to implement a form of door lock monitor. This makes it easier to ensure that everything is locked up for the last person that leaves.

Machine Access And Training

Some power tools, such as circular table saws, CNC-machines, lathes and press brakes can be dangerous, but almost all of them are expensive and can take damage quite easily when used inappropriately. With new members entering the machine park, it becomes necessary to provide regular training workshops where members can learn how to use the equipment safely. You may also want to ensure that only members, who have taken the official training, use these machines.

While this should be self-evident and could be implemented as nothing more than a behavioral code, it just doesn’t work like this in reality. Trained members are going to pass on their knowledge to others, which is good, but also comes with some amount of information loss, and sooner or later things start to break. There are various ways in how to deal with this, but the most elegant solution so far is probably the MACS Makerspace Access Control System, created by George Carlson and Kolja Windeler from the Texas MakerBarn. Their smartcard-based system only allows card holders that have received a proper training to actually turn on the machine.

Storage Space

Makers need the option to leave their projects and personal equipment in the makerspace. However, some need more, and some need less space, and you need an effective way to keep the clutter low. Therefore, put a price on storage space, even if it’s just a small one. The smallest possible hurdle that already avoids a lot of clutter may be if members have to purchase their own box, ideally a stackable standard size that is used throughout the space.

Material Management

The drawer with unsorted, mixed resistors, capacitors, and transistors, or the box with mixed screws may save one’s project on build night. However, keep the clutter low, and one preferred series of resistors is usually more than enough. Unsorted materials are a byproduct of makerspace build nights, not the primary raw material. Make sure it’s easy to store and retrieve all materials in organizer boxes (not just the electronics) and practice the art of throwing things away. You will encounter members or guests bringing their old toasters, printers and other curiosities that may be tempting to accept and store for later use in the material section. Unless you have a particular use for any of these, be it an immediate workshop or an imminent project, it will save you a truckload of disposal efforts (and costs) to say “no thanks” from the beginning and roll with a no-messy culture.

Self-Management

The Board Can’t Do Everything

Every makerspace needs a responsible management team of no less than three members to distribute the responsibilities. The board will initiate the board meetings, poll the members on important decisions, and oversee the whole thing. However, especially in NPO associations, the board members – and probably you if you’re about to start a space – often invest a lot of spare time in the administrative effort to keep everything going. If you don’t want to burn through board members at a fast rate, give space for and implement a self-managing culture.

Commerce In The Space

It can be extremely healthy for a makerspace to have a core group of individuals with a vested interest in the well-being of the makerspace. This can be a startup or a few freelance developers and engineers, or anybody who uses the infrastructure of the space more frequently, eventually becoming the active core. They substantially benefit from the makerspace and therefore are motivated to take a bit of extra care that everything is going well. Their role in the space is not much different from any other member of the space, but their motivation – based on a fair portion of self-interest – will spread contiguously and adds a whole lot to the self-management capabilities of the space. To implement this actively, many makerspaces go one step further and offer co-working space as well.

DIY Things

Due to the open nature of makerspaces, you will sooner or later find your space becoming an ecosystem for tinkerers, semiprofessionals, and engineers with a wide range of interests and know-how. On the one side, they are coming to build their projects, use the equipment, get input and learn things. On the other side, some of them will hold workshops to pass on their knowledge, which also helps to attract new members, service the machines and figure out ways to improve the overall experience. It’s the maker way, so do it yourself.

How To Spend Money

The money for the acquisition of new equipment must come from somewhere, and in an organization where the membership fees are the major income source, it may sound like a good idea to use these funds to buy equipment. However, be aware that there is a very attractive alternative to this top-down approach: earmarked donation campaigns. On the one hand, the raising and allocating of funds increases the administrative efforts for the board, since they have to gather quotes, make suggestions on what to buy and poll the members about them. On the other hand, there will always be members with a low frustration threshold if their membership fees are used to buy a piece of equipment that they deem unnecessary. At least if you are operating as a non-profit, it generally goes smoother to keep the expenses and membership fees low to stimulate growth, wait until a part of the crowd has achieved a consensus about what to buy, and then run a earmarked donation campaign among members and sponsors to buy the thing.

Grow

The first and the last thing you have to manage is growth. After you take the leap and go from 0 to 1, you need to reach a critical mass and find the right size for the makerspace in your region. Makerspaces create value for their communities, and therefore, they grow automatically to a certain size by word-of-mouth. Still, growth is a direct result of the amount of community work you’re doing.

Public Workshop Offerings

A full and diverse workshop schedule attracts new members like nothing else, so encourage your members to hold some or hire external mentors. Usually, every single individual in a makerspace knows something worthy to pass on to others, so make use of this resource.

The Tour

It’s a good culture to welcome guests, give them a tour and show them around. Guests will show up at your door at any given time, and it’s everybody’s responsibility to give them a little introduction. To these visitors, it is the first impression they get from the community in your makerspace, so be sure to do it right.

Local Events

Being present at local fairs and maker events is probably the most obvious action you can take to promote your makerspace’s presence, right after setting up a website. Yet, it’s the hardest thing to implement. You’ll typically find a certain reluctance among the members to leave the safe constraints of the space and present themselves at a corny stand at a fair. Since it takes a bit of planning ahead, it takes someone to initiate the preparations and sign-up the makerspace for the event. So, if you want this to happen, you need to engage the members to take action in time.

Build-Night

Offer a topic-less, come together once a week, with open doors for members and guests. It’s often called build-night, and even if it’s not the most productive work environment, it’s fun and has a huge retention factor to guests who get hooked up to the energy of making.

The article has grown long, but is still just a crash course of the things involved in starting up a makerspace. These are the social groups of time, and have the potential for great impact on the future of hacking, designing, and engineering. They are well worth the effort and time you and your friends will put into the task.

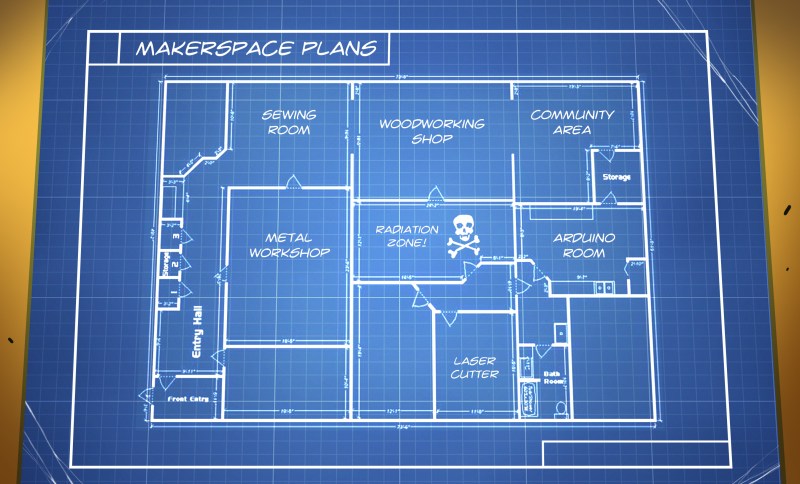

That floorplan in the header image worries me. In order to get to the bathrooms from the metalworking room, you have to either cut through a storage closet, or traverse the RADIATION ZONE. Also, there’s a room in the lower right corner that has no doors.

That’s where they keep the bodies of the people who annoyed them (not sure about the void in the top left corner, maybe lost treasure in that one).

I can’t help feel that the Crystal Maze would have lasted longer if they’d also had a “Radiation Zone”.

Obviously the room on the lower right is the evil mastermind lair, entrance is through the sliding panel in the washroom. The unmarked room on the lower right is for Goon/Minion/security guard storage. What worries me is that it is going to be impossible to keep the sewing and community rooms clean with all the sawdust coming out of the woodworking area. And of course the Radiation area is the Standard Issue Deadly Household Feature found in all sci-fi/adventure scripts. Much easier to maintain than a shark tank or Bladed Pendulum Boobytrap(tm).

I assume the bathroom is the one labeled “Arduino Room”.

Also known as “The little processor’s room”

Actually the “Radiation Zone” is just the kitchen, they have to label it that because people keep taking apart the microwave.

The room with no doors is presumably the server room, inspired by Noisebridge’s.

I spent two years on the board of directors of a large, well-established hackerspace (currently around 400 members, my tenure on the board saw growth from ~250 to the current numbers), the second year as president. While I was on the board we managed to finally file taxes for the last several years (which had never been done before) and submit our federal nonprofit application (which was approved a few weeks after my last term), which were both very important to ensuring the continued existence of the space into the future.

My best advice: build a relationship with a lawyer who is willing to work with you pro-bono, and consult them on -anything- you’re not sure about. Let the professionals do the professional work. Hackerspaces tend to collect armchair lawyers, and it’s much easier when you can say “This is what our legal counsel has advised.”

Our space is very much member-run, so the board exists to keep the lights on (literally and figuratively [i.e. deal with anything that’s a threat to the continued existence of the space]). A shocking amount of the board’s time was taken up with interpersonal disputes between members. Community is the best and worst part of a hackerspace, because while it will be a vibrant source of ideas, projects and the energy to keep things rolling, interpersonal disputes can make the place toxic and terrible.

As a space grows, a board that exists just to pay the bills and buy toilet paper will have to take on more oversight duties. Balancing the needs of the space and its members with the ideal of a cooperative, member-run organization is hard, and there will be growing pains.

Things that helped us:

* Using some kind of ticketing software to track stuff (We elected RT)

* Using some kind of member management system (We were (mis)using Zoho for a while, and transitioned to a homegrown Django app). Use this for sending ‘official’ emails like vote announcements and tracking membership status.

* Hiring an accountant. Again, let the professionals help you.

Things that hurt us:

* A member-written policy for handling disputes and complaints about other members.

* Needing to deal with complaints about harassment (of several kinds) without a solid plan and established prior procedures. Have a clear policy that defines what happens when someone’s accused of harassment or other shitty behavior and be ready to enforce it quickly. Indecision and reluctance to be ‘the evil board’ that punishes members will only draw things out and make everything worse. Interpersonal issues were the single largest source of stress during my time on the board, and distracted us from ‘more important’ things like taxes for a long time.

===

Running a hackerspace is challenging, exhausting and difficult. All that said it’s really, really rewarding to be able to look at a working space and feel like you helped it along.

Did your board create any “by laws?” And did you find a need to have visible cameras throughout to help “enforce” non-harrassment within the workspace, if not curtail any theft?

Bylaws were adopted when the organization was created (7 years ago or so). There are no security cameras in the space. We installed cameras on the entrances to satisfy the requirements of our insurance, but the membership is fairly vocal about security cameras elsewhere.

sounds like ps1. Except someone cut all the camera cables. God I hate people….so so much.

How did the member-written disputes policy bite you? And what sort of policy would you advise that isn’t member-written?

It was worded in such a way that it did not outline a clear, unambiguous course for resolving disputes. Any such policy should outline exactly what will happen in the event of a complaint so the board can paint-by-numbers to resolve disputes, without either party being able to argue about how it’s being implemented. If the board has to spend time discussing how to move things forward, the whole process bogs down.

We’ve just embarked on the IRS Form 1023 adventure and would like to compare ideas. Would you be willing to share your successful application?

I’m no longer on the board, but if you want to shoot me an email at derek (at) pumpingstationone.org I’d be happy to talk about what the process was like.

loans, thanks for the great addition to the knowledge base. It’s always a pain with the disputes. Once they’re there, they’re there, and as long as the involved troublemakers are around, they won’t go away. Managing them doesn’t make it better. You can start expelling people, but I think it’s better to maintain the right culture in the member base. Productivity kills trouble. It’s the slight alkaline milieu where acidity can’t thrive, and eventually, troublemakers leave on their own.

I’ve seen two Makerspace come into existence in the last couple years. Both started, kind of, at a joint meeting at my house. One group was eager to get started so found a space, moved in their personal stuff, and got at it. The other took a longer, planned approach and just had their grand opening awhile ago. That’s the Texas MakerBarn with MACS that Moritz mentioned. I’m in contact with both and they seem to be doing well. Both groups’ approach to getting started has advantages and disadvantages. I know “jump in” group had to do some reorganization last year but they survived. They’re a family run group so probably avoid a lot of the group dynamics.

I’m our church Treasurer so sit on the Board of Trustees. It’s not unlike running a Makerspace. There are always plenty of issues to deal with. It’s not for the faint hearted. I do find my activities mostly rewarding although at times it can be overwhelming. (Why did I just agree to another 2 year term?) The people issues are always a challenge. You’ll notice I didn’t jump into the organization of either of the Makerspaces although I kibitzed and helped some.

The cost factor is really the kicker here, and it bears extensive study to make sure you’re not pricing out the people you’d most want to attract.

Example: A semi-local hackerspace (a really good one by all appearances) recently opened a local branch. The local branch would be reasonably convenient to my normal daily commute, offers a good number of potentially interesting classes, is well stocked with a good consist of hardware, partners with a local community college, etc… they’re doing everything right. But… the “just to get in the door” membership level is $75/month, and the “expanded” membership level is $100/month.

Now, in reference to the basic level, the expanded level is a great deal. The expanded level offers free access to classes that would otherwise cost at least as much as the difference in cost between the membership levels (for just one class). Thus, as long as you take more than one class per month, you’re easily getting your money’s worth.

But, in reference to what I’m able to pay per month, the basic level is incredibly expensive. $75/month? WTF?!? Maybe that’s pocket change for some folks (I’m sure it is, the area of location isn’t too bad off), but for other folks (such as myself) with budgets that are already tight, that’s *a lot* of money.

To answer the obvious troll questions: I very rarely go to starbucks, I have a pay-as-you-go cell phone through Ting that I barely use anywhere other than on wi-fi, I cut the cord long ago and watch free OTA television, and I buy good tools but only when I find them at swap meets, junk piles, or on deep-discount. I don’t think I’m alone in this.

Sure, life isn’t fair. Life is what we make of it. Choices matter. Etc… Those are the speeches that I both give and live. So I’m not angry at the local hackerspace for doing things how they’re doing them. It’s very likely that, given their own constraints, those prices are the lowest they can offer and still keep the lights on and the facility fully functional. I get that. I’m happy for them. I’m happy for those that can afford such a monthly sum on a regular basis. But all that to say, their overhead is small and their volume is such that they can sustain themselves and offer a quality product to their members. But that’s the lowest it seems they can go on price in a reasonably well-to-do area, and it’s still out of reach for *a lot* of people in the area.

But what about hackerspaces in less well-to-do areas? Ones who are facing higher costs on multiple fronts, but who are trying to operate in areas that are down on their luck or are really experiencing the worst of the recession, etc… How on earth are they to survive in those areas and provide the necessary opportunities to the folks in their communities who would otherwise be completely unable to get access to such tools, knowledge, ideas, and opportunities, all of which may be essential for folks to be able to rise above their circumstances and make a life for themselves and their families?

The cost factor is a real challenge, and requires much thought. In order for the maker communities around the country (and the world) to flourish, it seems like significant investment is required from those (individuals, companies, foundations, etc…) with the means to offer it. The first and biggest challenge of a local hackerspace isn’t learning a new technical skill or gaining experience in operation of a novel tool. Rather, that first and biggest challenge is one of funding, sustainability, and outreach. Solving that challenge (or making great strides to that end) will allow everything else to follow.

I’m guessing this place is a for profit space, which is fair, but I’m guessing that because all the spaces I am familiar with have a $25 entry level, and will negotiate service hours with the truly starving student. These are all spaces that are run by volunteers, staffed by people who would otherwise be tinkering around in their own basement and located in parts of town where no normal person would locate a public facility. Most are struggling on the razors edge of fiscal sustainability while giving away training, tool usage and entertainment to anybody who can find the place. I hung out worked on my own and other people’s projects and was generally treated as a member at several spaces for years before I started paying dues. I reserve the term Hackerspace for a place that is technology centric, member run, and open for public use on a regular basis. A true Hackerspace is a labor of love, a pearl of great price, and a trial balloon for a better world. Those others, not so much, they are shinier and have all the cool toys, but no reason to hang around after your work is done.

I’m a director of a Canadian hackerspace with ~30 members. Rent and occupancy costs for 1100 sq. ft. are about $1500/mo. That’s the entirety of our $50/mo/member revenue, with nothing leftover for maintenance and upgrades. We’ve discussed whether we could do with less, but on build nights it’s already quite cramped, and we have equipment on every shelf an in every cupboard. It’s also really difficult to find smaller industrial spaces — 1400 sq. ft. seems to be a standard size in our city. It’s definitely limiting for us to get members, but we’re at a loss for ways to offer cheaper rates when the bills have to be paid. Perhaps we could place limitations on members who pay less, but what could we leave out? It’s a difficult problem for us and there’s no clear way to avoid it.

Great post. I would like to be a member of my local Maker Space but the monthly cost is way too high for me to justify being a member for the amount of use I would get from it. I consider it far better value to put that money into buying my own tools and supplies instead.

The average I have seen is $30/mo +/-5. With a few outliers in the $45-50/mo range.

The for-profit spaces (TechShop &c) tend to charge by the hour or class at a rate most visitors to this site would find high.

I’m surprised this article didn’t mention https://wiki.hackerspaces.org/List_of_Hacker_Spaces which I would also encourage those who run a ‘space to register at.

Even at $30/mo the community at any given hackerspace is it’s most valuable commodity. $30/mo for a year can outfit most peoples garages with a decent spread of tools far better suited for their own interests so your core facility better provide something more than shiny tools.

The community is absolutely the most valuable part of a hackerspace membership. If you join my space, you are now connected with several hundred people with skills in every category, most of them happy to share knowledge. It’s an amazing place to learn – the tools are good, too, but they’re really kind of secondary to our mission.

It’s true, makerspacing is expensive, at least when you see it as a hobby, which is fine. As a hobby, you’ll compare it to a netflix membership or a cheap fitness studio and say, hey, I could get this or that for the same price. However, it also can be an investment in your community, your knowledge and inspiration. These things are, in a way priceless. On the number side, if you have a hundred members and each pays $25/mo, then you have $2500/mo to cover all the cost, from the rent to the lawyer. You also need to be located in an area where that member count is feasable. Many spaces offer student rates and lower fees for socially deprived members, but even at a disount, if you see it as a hobby, it’s an expensive hobby.

“…this is reserved only to the small community driven factories named fablabs.”….whaat???

Board of directors.

President.

Not for profit IRS forms.

Yeah you guys are hardcore hackers.

Your tone indicates that you don’t think hackers should worry about that sort of thing.

My space exists to provide resources to everyone – we have regular classes, events where people can learn about art and technology and do outreach. Education is a valuable pursuit, and being interested in it doesn’t diminish any of our members’ status as ‘hackers’ in my mind.

No, I understand completely.

In Soviet hackistan, hackerspace is job that YOU pay to show up to.

The word hack has been repurposed from my working definition of it. Guess it’s something I’ll have to get used to.

You don’t pay taxes while big corps have to, another hack!

Good for you guys though.

Outreach is non-profit speak for marketing, correct?

>The First Aid Kit

>It’s the first thing you need to get, and it deserves being mentioned first. Every other item can be bought when the need

>comes up.

This is true, the problem is that they are a lot of people that don’t know anything about first aid and so don’t want to help if there is a problem because of the fear of making things worse… I think some first aid class dispensed by a professionnel would be a really good thing for makerspaces.

And don’t forget fire-extinguishers! (and instruct people how to use them)

One of our directors is a dispatcher for EMS. Although we have many fire extinguishers, if he does the orientation, he describes their correct use as “to be ignored while rapidly walking past them out the exit”.

I’ve been searching, but can’t seem to locate furniture/storage/organizers for the specifics needed for a makerspace, and I hope someone here has the answer – besides making the furniture/storage/organizers. Yes, if I had access to the tools and materials for everything that is needed, that would solve my problem, but I don’t currently have a makerspace. So, I am still going to ask: Could you refer some furniture retailers that are functional for keeping a makerspace organized (the storage of supplies and possibly even projects), resilient to the abuse it is bound to take and have a “polished” refined look that is also easy to maintain?

what software is used to produce those blueprint layouts? they look very nice, and I’ve seen them on various places like the fortify subreddit

I have been a member of a large well-established NPO Makerspace for several years (but not on the Board). I can relate to a lot of the issues that “loans” and others have discussed above. When we were a small Makerspace, the “Be Excellent” credo was successful. Now that we’re huge, there is a wide disparity in how people interpret this. We have a set of documented rules and policies but for the most part, compliance is voluntary. We’re struggling with how to enforce these things. We waste a lot of organizational calories dealing with infractions that, in the overall scheme of things are probably petty, but really annoy a lot of the members and impact everyone’s ability to use the space (cleaning up after oneself, respecting tools, storage use/abuse, etc.) Some particularly egregious infractions can invoke a suspension or ban, but for nearly everything else we just trust people to “be excellent”.

Like I said – that isn’t working very well. I would appreciate any insight into how other Makerspaces handle that type of situation – particularly if you have a systemic system for identifying, escalating, and dealing with various rule infractions.

Harassment is the one area where we have procedures in place, but everything else we could use some ideas. I’d be open to either the carrot or the stick.