We’ve had two previous articles in this series on turning a personal electronic project into a saleable kit, in which we’ve examined the kit market in a broader context for a new entrant, and gone on to take a look at the process of assembling the hardware required to create a product. We’ve used an NE555 LED flasher as a simple example , from which we’ve gone through the exercise of setting a cost of production and therefore a retail price.

The remaining task required to complete our kit production is to write the documentation that will accompany it. These will be the instructions from which your customers will build the kit, and their success and any other customers they may send your way will hang on their quality. So many otherwise flawless kits get this part of the offering so wrong, so for a kit manufacturer it represents an easy win into which to put some effort.

Keep it Simple

It is important to remember that the reader will never have seen the kit before and will not have your level of expertise on its operation, so you should pitch them as though at a relative novice. Imagine that a not-very-technical person is about to build your kit, and try to provide enough information for them to proceed without losing their way. This may at times seem as though you are pitching it at an impossibly low level, but your more tech-savvy customers will understand and take away only what they require.

We’ve produced a set of sample instructions for our NE555 LED flasher, and we’ll now step through them. You can download your own copy of the Hackaday LED flasher documentation (PDF). How you write your instruction leaflet is up to you as everyone has a personal style of their own, so these instructions will represent a particular style which may be different from that which you have in mind. They should serve as something of a guide though which you might wish to take inspiration from if you have never written kit instructions before.

Sections

Our NE555 LED flasher instructions take the form of a set of clearly delineated sections that introduce the kit, describe its operation, take the user through its components, give instructions for building it, and finally describe how it should be used. We’ll now step through each section in turn.

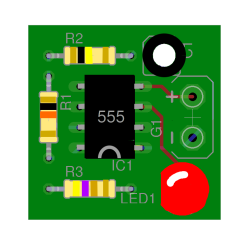

The very first paragraph is a short friendly introduction with a picture of an assembled kit. It doesn’t have to do much beyond saying what the kit does, it’s only an introduction. In our case the picture is a mock-up, this is only an example for this series of articles so we’ve not made any boards.

Following the introduction, we’ve written a section describing the tools and techniques needed. In this case it’s a pretty short piece of text because there are no special techniques required, but you might wish to expand here if for example your kit has surface mount components. It’s important to remember that some users may not have encountered all the skills required, your job here is to equip them for anything they might encounter.

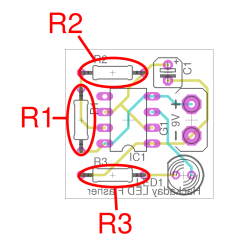

The techniques section over, we move on to the components. Some kit manufacturers produce a table as a checklist here, but this is a simple kit so we’ve described those components that might be difficult to identify. You may wish to take a hybrid of the two approaches.

Once the user can identify everything, we move step-by-step through construction. This progression should be based on your experience of building the prototypes, you should note down the progression that worked best for you. Put three to five components in each step, and include a diagram showing their placement. You’ll notice our instructions have three-band resistors for ease of description, it’s likely that a real kit would come with five-band components.

The user should now have a completed kit. The next section should take them through any setup, fault-finding or troubleshooting required to ensure the kit is ready to be powered up. In this case it’s a short section as a 555 LED flasher is a very simple circuit, but you might include voltages and currents to measure with a multimeter before hooking a computer peripheral up, for instance.

There should now follow a section detailing how the kit should be used. Very short for an LED flasher, but for instance you might detail whatever software might be required for a computer peripheral kit, or how a more complicated kit should be connected up.

With building and operation out of the way, all that is left are appendices. We’ve put the circuit diagram in here but it could certainly go in the body of the document. You might find tables of values in here, or legal and regulatory information.

Test and Review

Once you have written your instructions, you’ll have to ensure the quality of your work. Ask your friends to proofread them, and if you can give a sample kit to one of them with the instructions to follow as they build the kit. Be prepared to incorporate responses to any criticism, imagine that the proofreaders represent real customers.

Having honed the document, it is important that you then present it in as good a way as possible. Print on good quality paper with a colour laser printer, and use double-sided printing if you can. They are as important to the kit as any of the components, so they should be treated accordingly.

If you have followed this series from the beginning, you should now be equipped to learn about the market in which your kit will compete, to turn your prototype into something closer to a product, and to create a set of top quality instructions for your customers to build it from. In the next part of this series we will bring what we have created in this and the previous part together as we examine kit packing and the process of producing your first kits for sale as products rather than simply as prototypes.

Nah, I’m suspicious of glossy instructions, hardcore documentation is in black and white :-p

Or a .pdf file.

Right any format that hasn’t left the developers and techs as cogent information, then passed through an art and design department, then had marketing correct the proofs.

This. Coming from a company whose art department regularly right-clicks and accepts the first autocowrecked for every engineering term not in QuarkXpress’s dictionary, swaps out the Greek symbols in equations to make them “look prettier”, rewrites (poorly) the sentences they don’t understand, then dolls the whole thing up in glossy ad-tastic extravagance on drool-proof paper that makes the engineers (target audience) cringe.

a .txt file that comes on a 5 1/4 inch floppy disk.

Depending on how complicated it is to use your kit, the instructions may be just the beginning – you may also need to have technical support available, at least over a web forum or email, if using the kit is going to be something complicated. But a good instruction manual can help reduce how much work the support team (which is probably going to be you yourself at the outset) will have to do,

Make sure that there is a link in the instructions (or somewhere in the kit) that points to a web site where current and refine documentation can be downloaded.

And most importantly: If you end up making (hardware) revisions, have instructions for each revision available. Because wrong information is worse than no information at all.

Not a huge issue with a simple example like this. But yes.

Thank you, Jenny. Good stuff.

Did you actually give it to someone else to proofread? I’m wondering which acre I should be taking? ;) (2.3.2 step 1)

Hoist by my own petard! :)

Having used it a couple of times, I think the Gold Standard in assembly documentation is the OHAI stuff at Aleph: https://ohai.lulzbot.com/

Large, clear photos, good step breakdowns and included tips and hints.

Remember that some of your users may actually be color blind, and that your instructions may be used in poorly lit basements in poor hackerspaces. In other words, don’t rely on colors alone to convey information, always make sure that each color goes with a distinctive pattern (or explicit printed color names) so that it’s readable also in gray scale.

That’s sort of tough when things like through-hole resistors are distinguished solely by color codes.

Recent development: Through-hole resistors are also now distinguished by resistance value. All you need is a piece of test equipment called a multimeter.

:-P

.

Right just set it to blue for the resistance scale.

And connect one gray cable to each leg?

No kidding, I once met an auto mechanic that was colour blind, it was waaaay back when a mecanic repaired stuff like generators instead of replacing units.

Only problem, the rectifier diodes was only colour coded, he made himself a testjig with a taillight bulb and a battery and never told anyone he was coulourblind he was “just testing the diodes”

I think it was because he was afraid that his drivers licence could be revoked or something if the colourblindness was known..

I believe in a later part of this series dealing with packing I advise labeling the tape with the value.

It may be more than most kit makers want to do but a look at any of the Heathkit “how to assemble” manuals might be informative. The check boxes would be overkill but when my son and I built Hero-1, it was helpful.

Interesting read, for the https://kitnic.it site I have been thinking a lot how to incorporate build instructions along with the files and parts list. One idea I had was to show the location of the part on the board when hovering over it in the BOM.

When creating instructions, make sure they work well printed both in color and in black and white. While color printing looks snazzy, printing in b/w is often a good way to shave a little money off your bottom line for the kits. When I ran a print shop, most people wanted color until they found out the price difference and suddenly b/w was good enough.

Get a big ole LaserJet… one of the ones you can get a supersize reman toner cartridge for, can get you as low as 1 cent a page, 1.5 cent if you only want to buy one toner and box of paper at once. Then you can laugh at anybody trying to sell you “cheap to run” printers at 4c page, or bulk black and white printing at 2c a page if you want 5000.

Colour, for at least the first page, sells your kit if people see the colour picture through the plastic bag. Pile of kits with colour pic versus pile with B/W pic, colour one shifts.

On a laser printer – at least on my one – it only uses colour toner for the little colour pic of the board, the rest is the same cheap black toner as in a black and white print.

“…an exceptionally good mastery of one’s native tongue is the most vital asset of a successful kit designer…”–paraphrase of Edsger Djikstra

+1 :)

I sometimes think I don’t sell kits, I sell instructions.

This series has great info, but it seems way to “educational” level.

How about a V2: include a microcontroller with programming, require a dedicated test rig and most important of all, actually sell it!