What if you didn’t have to risk your life to disconnect the power during a catastrophic storm? That’s a question many people in Houston were asking themselves as they watched water from Hurricane Harvey and other storms surge through the streets, swell in the gutters, and flood their homes.

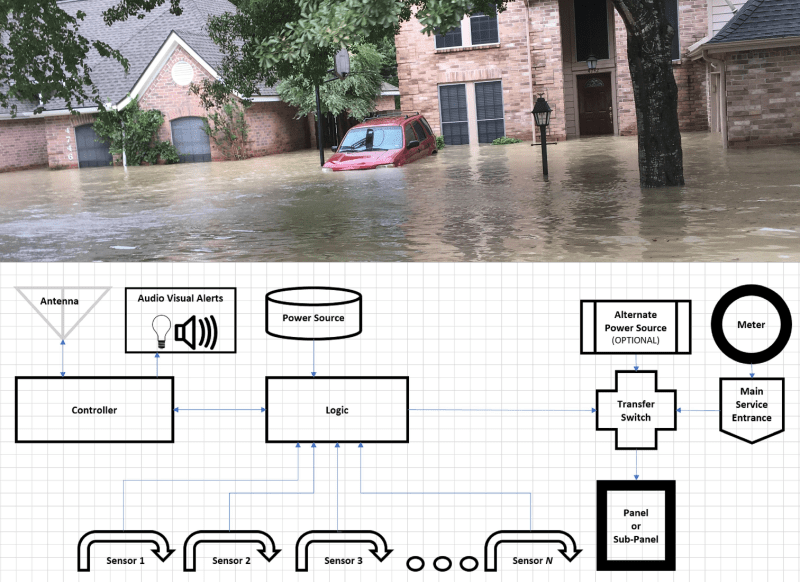

Among these Houstonians were engineering students [Jon] and [Cyrus Jyan]. They watched as homeowners fought to safely disconnect their homes from the power grid and said, it shouldn’t have to be this way. They designed the Flood Fault Circuit Interrupter to monitor target areas and disconnect the power automatically when a credible threat is detected.

Among these Houstonians were engineering students [Jon] and [Cyrus Jyan]. They watched as homeowners fought to safely disconnect their homes from the power grid and said, it shouldn’t have to be this way. They designed the Flood Fault Circuit Interrupter to monitor target areas and disconnect the power automatically when a credible threat is detected.

The FFCI is built on top of existing protection schemes like GFCIs and Arc Fault Circuit Interrupters. It isn’t meant to replace them, but instead tie them together and turn them off based on input from float switches.

As floodwaters rise, an EEPROM does a lookup and compare to decide if the threat is enough to shut it down. If so, an alarm signal to a shunt trip breaker can either throw the whole system to OFF, or else switch over to an alternate power source. The system is built around a standard security panel and keypad interface that supports 12 V alarm output. We particularly like the float switch enclosures that allow water to enter while keeping out debris.

I’d probably keep it simple and use a mechanical linkage to trip a service disconnect breaker when a float reaches a specific height, likely below the height of the outlets in the house. A float designed for a toilet tank would work well, and a mesh cage around it would prevent anything from accidentally tripping it.

One thing you might want to watch out if it was done that way is to ensure that it wouldn’t keep flipping the power on and off. Something like a simple float might work, but if there’s any sort of waves, it could keep flipping the power on and off.

The Shunt trip breaker would require you to manually reset the breaker in order to turn power back on, so you would have to worry about it oscillating with waves.

That’s a good idea, but every main disconnect I’ve ever encountered would require a really large float to trip it off.

Easy. Make the float switch a short into the line, causing the breakers to flip as designed. No wait, you’d need a fairly thick conductor for that to not cause a fire.

Even better, make the GFCIs trip by pulling live to ground. A microswitch should suffice.

Never rely on shorting out to disconnect. Not because it won’t work. But often breakers (especially main feed ones) are only rated for a limited number of operations and you do need to deal with a massive current for a brief moment on that switch.

While that would certainly do the job, I would imagine the fire risk to be larger than the electrocution risk. Shorting a 400A incoming service would be pretty exciting…we had a 50A/480V circuit short out in the shop and it sounded like a gun shot, then caught the machine on fire; granted this is industrial 3-phase power and not a 240V split phase service.

You can make it snap acting, where the float trips a much more powerful spring that turns off the main disconnect.

It probably would end up copying the trigger assembly of a gun, where the trigger takes very little force to actuate, but moving the slide/bolt spring takes a large amount (see open bolt gun designs for details). Also, a gun trigger is a extremely reliable mechanism that has hundreds of years of refinement behind it.

Have you heard of this great new invention called the lever?

Nice idea, but shouldn’t this be the job (or the responsibility) of the electrical company (utility)?

So we need to invent also a gaz breaker in case of an earthquake?

What about tornados?

>> So we need to invent also a gaz breaker in case of an earthquake?

I used to live in Southern California, and you did have to have an automatic shutoff valve on the gas line.

They were mandated just as I was relocating, and I had to install one before I could sell my house.

They were basically a little chamber with steel ball balanced balanced on a ledge over a gas inlet nozzle. If you shook the valve body the ball would fall down onto the cone-shaped nozzle, sealing off the gas. It was pretty sensitive, you could see how it worked through a little window and test it by giving it a little smack. There was a little mechanism to manually reset the ball.

In Japan, the earthquake gas cutoff is built into the gas meter.

We also have earthquake circuit breakers that will turn off the power in a strong enough quake.

The simplest retrofit for older breaker panels that I have seen is a steel ball bearing on a string that you tie through the lock-out hole in the breaker lever.

The ball bearing then sits on a little shelf you stick to the panel next to the breaker and in a strong enough quake, the ball bearing falls off the shelf and pulls the breaker to the off position.

Won’t work for sideways breakers, but practically all domestic breakers are installed in the up/down direction here.

Now that’s beautifully simple and elegant, I love it!

I wonder if they have really big ones in the power plants?

Here is the product. It’s so simple and effective. :)

http://nip-inc.com/swdanballiii/

“or else switch over to an alternate power source.”

If you are worried about water and electricity, I’m not sure why you’d want to switch to another source of electricity.

Unless you are talking steam, wind, or horses…

Step one – don’t buy/build a house in a flood zone.

Step two – demand that laws change, so that instead of the state paying to rebuild said houses after a flood, they pay the owners to move out and level it with the ground.

The flood zones are known and not a secret. Either build the house to cope with it, or don’t build there at all.

As for the switching problem – get yourself a nice fiberglass pole and attach a tool (probably a hook of some kind) to it, so it can be used to open the box and trip the breakers without touching anything potentially live with your bare hands.

It has the bonus of being usable to move downed power lines relatively safely.

Step three, plant a forest with historically native trees.

Step one –

In my town the 100 year flood zone flooded twice within 10 years, about 20 years after houses had been built.

https://water.usgs.gov/edu/100yearflood.html

If you live in a flood zone it’s a lotto x % chance per year, sometimes you win that lotto every year.

There is a bridge in my area with a “2.8m clearance” sign on it. This bridge carries a major railway line over a road connection. During the floods that hit my area in 2017, that bridge (and the railway tracks that crossed it) were totally submerged along with houses, roads, cars and more.

Simply saying “dont rebuild/repair flood houses, move to a new location” doesn’t always work when you would need to move not just houses and apartment buildings (some of which were flooded, others of which were high enough not to flood but got cut off by floods in the lower areas) but a major rail link, train station, shopping centres, commercial buildings and more all of which were either flooded or cut off by the floodwaters at the peak of the flooding.

Moving that many people away from the rivers where they flood just isn’t going to happen.

May I introduce you to Miami?

I expect it will be abandoned in my lifetime (another 50 years if I’m lucky), along with much of southern Florida.

I live in Houston. Harvey was a different type of storm than what we’re used to.

The typical flood profile we get is storm surge. That’s what happened during Ike about a decade prior: the hurricane comes and pushes water up through the shallow bay and floods the coastal areas. This also wipes out the shield islands like Galveston.

Harvey did that when it hit Rockport, along with massive wind damage, but then it turned north and essentially created a tunnel through the air between Houston and the Gulf of Mexico. And then it just sat there. Raining. We received close to 60 inches of rainfall in the course of a couple of days. Much of that was over the course of several hours.

Lots of folks whose homes were fifty years old and had never flooded ended up losing everything because of that. The water collected inland and had to flow out to the Gulf. My house, which is in a coastal flood zone, didn’t flood during either Harvey, Ike, or Allison. Will it flood in the next storm? Maybe. That’s why my insurance costs as much as it does.

Why do people still live here, or anywhere else near the coast? It’s a major industrial port with a Space Center. It’s a huge economic center. Jobs are here, and the people follow those. That’s why I moved here.

Yeah, I just wish the people who lived beneath Sea Level in New Orleans hadn’t rebuilt in the same location after Katrina(sp?)

I mean, that seems obvious to me…

This really should be a non-problem these days. Most (all?) RF-connected “smart” meters can be disconnected remotely by the utility company at will. And they know where you live. Go ahead, ponder that for a while, all you guys with SDRs capable of transmitting… (ps: the serial number is displayed on each meter)

Doesn’t the city cut down the local grid during floods? So that limits it to small area floods and the reference to major hurricanes is perhaps a bit overstated?

Houston Resident here.

They didn’t for an hour or two, at least in my area. By the time they cut it, the water was at my knee, by the time it was cut all over the neighborhood I was up to my waist. Less than 30 minutes had passed.

Never flooded before, this time around, I got “rekt” as the kids say.

These water detetors have been made from 2 push pins, a clothespin and an aspirin or sugar cube for 40+ years.

They used to be combined with a buzzer and put under washing machines to detect sprung hoses.

Make sure that the sharp side of one push pin connects with the flat side of the other pushpin if the sugar melts to improve the chance of pushing through oxide layers. (Some stainless material would probably be better here).

Another solution is to simply build a concrete cellar under the house. Can be put to good use during normal times, and if done properly the house would simple float on the water during a flood.

Lot’s of living boats are made out of concrete buckets.

Flood waters often enter through toilets and other drains.

When I was a child, I heard of a man in Kansas who wanted to have a basement when he built his house in an area with a high water table. He made it water proof, only to have the house end up floating. He ended up drilling holes in the basement walls.