For most of human industrial history, the blacksmith was the indispensable artisan. He could fashion almost anything needed, from a simple hand tool to a mechanism as complex as a rifle. Starting with the most basic materials, a hot forge, and a few tools that he invariably made himself, the blacksmith was a marvel of fabrication.

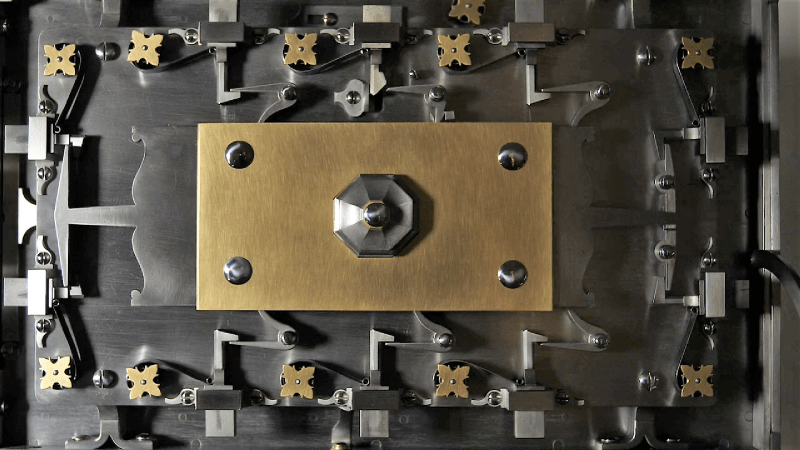

If you have any doubt how refined the blacksmith’s craft can be, feast your eyes on [Seth Gould]’s masterpiece of metalwork. Simply called “Coffer”, [Seth] spent two years crafting the strongbox from iron, steel, and brass. The beautifully filmed video below shows snippets of the making, but we could easily watch a feature-length film detailing every aspect of the build. The box is modeled after the strongboxes built for the rich between the 17th and 19th centuries, which tended to favor complex locking mechanisms that provided a measure of security by obfuscation. At the end of the video below, [Seth] goes through the steps needed to unlock the chest, each of which is filled with satisfying clicks and clunks as the mechanism progresses toward unlocking. The final reveal is stunning, and shows how much can be accomplished with a forge, some files, and a whole lot of talent.

If you’ve never explored the blacksmith’s art before, now’s the time. You can even get started easily at home; [Bil Herd] will show you how.

Thanks to [zit] for the tip [via Gizmodo].

That is a true masterpiece!

Wow

Great piece of work. Artistry is for sure.

That is amazing.

its a shame that hand made artwork like this is the exception and not the norm.

I have only one question, why is wrought iron no longer produced? is it because the methodology has been lost to time or do we not have the materials any more?

Wrought iron is alive and well, used mostly in decorative fencing here in the coastal south west USA. Local metal shop (industrial metal supply) offers premade sections to cut and combine into all sorts of designs. Maybe different in your area.

I am willing to bet that that is not real wrought iron, just mild steel. Real wrought iron went away when mild steel became much easier to make, therefore cheaper. There are a few places that still make it for special ornamental purposes, but it is very expensive, mostly due to the very labor intensive way of manufacturing it and the now uniqueness of it.

I know for a fact that Seth used salvaged wrong iron, from wagon tires, boat chain, and other scraps. He does this because of its machinability, particularly regarding files.

fyi: The material is the same, only the process is heavy machine assisted/automated and can be done cold… lower material properties? yes for sure, does it matter for a fence: nope.

metalurgically yes,. but the purity is vastly different. mild steel is about as close to pure elemental iron as you’re going to find. wrought iron has slag inclusions, air pockets, oxide lamination, erratic grain structure variations, bits of coal, etc. from the non-molten refining process. Anywhere wrought was used historically, the material properties can be readily subbed with mild steel

from the linked site: “Wrought iron is no longer manufactured, so each piece needed to be forged from salvaged material.” I have also read in other places that the wrought iron that you can get today is not actual wrought iron but a look alike.

From wikipedia: “Wrought iron is no longer produced on a commercial scale. Many products described as wrought iron, such as guard rails, garden furniture[4] and gates, are actually made of mild steel.[5]”

To answer my own question from the begining, it seems like the process for making traditional wrought iron (99% pure iron) is just too expensive when compared to other metals. also from wiki:

“It has been estimated that the production of wrought iron costs approximately twice as much as that of low-carbon steel.”

“A commercial source of pure iron is available and is used by smiths as an alternative to traditional wrought iron and other new generation ferrous metals. “

Nobody in the steel industry wants [quote=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wrought_iron]It is a semi-fused mass of iron with fibrous slag inclusions (up to 2% by weight), which gives it a “grain” resembling wood that is visible when it is etched or bent to the point of failure.[/quote] But if there are enough artists and tradional smiths willing to pay the price it may keep continue to exist in niche applications. But who wants to pay twice as much for inferior (in strength) material?

Wrought iron has the property of being rust-resistant without the addition of chromium and nickel – a rare property among steels.

Presumably in days gone by, blacksmiths would buy their iron in rough ingots, or maybe even as ore, and make it into whatever they needed. Wrought iron, AIUI, is iron that’s been beaten flat, folded over, then beaten flat again, etc dozens of times, perhaps hundreds. Lots of times. That’s what gives it it’s fibrous structure, and it’s bendy stretchiness.

Since you can wright iron with a stone forge and a hammer, I presume Jesse could do it, but he’s got a limited lifespan like the rest of us, and nobody was willing to pay him to do that all day for however long it would take. So it’s more convenient to recycle old material. It could never be impossible! Such a hugely common art can’t disappear completely in such a short time.

I suppose you could maybe invent an iron-wrighting machine with some heavy-duty automation, or else set up a 1700s workshop in Africa somewhere and teach a few locals to do it, supported by the limited artisan market in rich countries. The logistics of running it though might be a lot to ask.

There’s probably no way to do it that’s economical with the price people are willing to pay. So it’s cheaper to take advantage of workers long dead, who had no other option, and wrought their iron cos there was nothing else to make things out of.

I am a blacksmith of 4 years now (and a tool & die machinist and watchmaker) and I love that Hackaday covers everything I love occasionally. And I love even more that there are people here like you guys who actually educate people on things like this.

I wish there was a simple post like function here to promote people like this who forward real knowledge of the subjects, often esoteric to the masses

“two years”

Are you willing to spend two years of your paycheck to buy one of these?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Puddling_(metallurgy) goes into significant detail about why wrought iron is so difficult. Not only is it labor and skill intensive, the starting materials aren’t common anymore because there’s no demand for them as mild steel is superior, and it doesn’t scale, so truly mass production isn’t possible. There are avenues for automation, but that’s hard to justify when mild steel is already cheaper and stronger.

You can buy new wrought iron.

Once a year, the Blists Hill iron foundry makes it. It’s not strictly a commercial thing though, as it is part of the Ironbridge living Museum. From what I know, you have to order early!

Cast iron, wrought iron and mild steel are all very different materials. Anyone saying mild steel is “better” should visit Ironbridge, where they can see a bridge made of (wrought) iron that *doesn’t rust*. Mild steel would’ve long ago disintegrated.

As for why things aren’t hand made? Machines do it, per part, far cheaper. Plus, lots of stuff is hand made in China by poverty wages that far undercut what I could live on. But, if you are prepared to pay, you can have bespoke, hand crafted locks on your doors. If you’re really up for it, you can get *brand new* ones hand made too, with a key. A new key will cost you *from* £150, so be careful with it.

Blacksmith here…

“Wrought Iron” has two meanings in the modern vernacular. One is “iron or iron alloy which hath been wrought” and the other is a material definition. The material is an agglomeration of relatively pure iron with ferrosillicate fiber inclusions. The best quality material will have as many as a quarter million ferrosillicate fibers per square inch (39000 per sq cm). The material properties of old style wrought iron lend themselves more fully to art forging than do the modern alternatives.

The material is no longer made in any appreciable quantity. It requires skilled labor over long times to produce relatively limited quantities. Costs per unit mass put wrought iron well outside the realm of any but artistic use. It runs between four and six times the cost of commonly available modern material.

But when one can get it (and afford it), it is a sheer joy to use. Be sure to work it HOT. It will crack if worked at the temperatures modern materials need. Modern materials would be ruined by heating to the optimal temperatures for the old material. Different material, subtly different technique. Also: be very aware of the linear anisotropic nature of wrought iron. One can get away with a whole lot of things in modern material that would cause an item of the old stuff to fail

Wow. Interesting project and interesting video as well, thanks for sharing!

Not only is he very skilled, the box looks amazing, with a fantastically complicated locking mechanism, and the film is great, with hammer blows and other noises matching the soundtrack. I give that an 11 out of 10. To be honest though, if I were a bad guy and wanted whatever he had in it, I would just destroy the box to get into it. That would be a shame but that’s what bad guys do.

Heck, if I was a bad guy, I would commission him to make me a box like that.

The point of the strongboxes is three tier security: something you have, something you know, and something you are.

First, you are the only person who can get to the box. If it’s bolted down inside your mansion/castle, nobody else should be able to get in past the guards. But if they do get in, there’s something you have that they need, which is the key. But if they do get the key, there’s something you know that they don’t, which is how to operate the lock.

If you can just grab the box and run, no security is sufficient.

I have a teeny suspicion the soundtrack was edited, and the video as well, to fit with the music.

@Greenaum Noooo, you don’t say? I thought it was filmed in front of a live audience.. :)

Honestly, I think the audio/video editing and presentation is really amazing in it’s own right. Maybe not on the insane crafting dedication-level of the coffer itself, but certainly ambitious and skilled enough to fit beautifully with it.

Great work of all involved, truly amazing!

No. The box was designed to be built in a specific cadence.

That is beauty made real in metal

It’s nice to see that when lazy “conceptual” “art” comes up on here, we’re no more impressed than any other turd with an LED stuck on top, but when there’s proper craftsmanship, that takes strong, skilled arms and a long time, we all go wibbly at the knees.

What plans did he follow and where did he get them?

I doubt he used one. However there are existing locking boxes like this from centuries past. You can see one in Hereford city centre’s museum (the separately standing Black & White building by the bull statue, in the pedestrian area), and one at Edinburgh’s Museum of Money (HQ of Bank of Scotland, halfway up the Mound), and there are certainly others.

Obviously he’s drawn up his own version, and brought it to life!

thats the sexiest thing ive seen all damned day!

stl files?

Pornographic….

I have a serious real fetish for historical strongboxes and masterpiece rennaisance locks.

This fulfills my fetishes. Hard.

I had no idea anyone else was thinking of or making these. This is what I eventually want to make with my blacksmithing and other skills. I love Hackaday for posting stuff like this occasionally, and if you like this kind of thing, your meccha is the Victoria and Albert museum in London. I’m sure he has visited it at least once for inspiration

Who on earth posts a video that one cannot adjust the sound on?!