Did you know Britain launched its first satellite after the program had already been given the axe? Me neither, until some stories of my dad’s involvement in aerospace efforts came out and I dug a little deeper into the story.

I grew up on a small farm with a workshop next to the house, that housed my dad’s blacksmith business. In front of the workshop was a yard with a greenhouse beyond it, along one edge of which there lay a long gas cylinder about a foot (300mm) in diameter. To us kids it looked like a torpedo, and I remember my dad describing the scene when a similar cylinder fell off the side of a truck and fractured its valve, setting off at speed under the force of ejected liquid across a former WW2 airfield as its pressurised contents escaped.

Everybody’s parents have a past from before their children arrived, and after leaving the RAF my dad had spent a considerable part of the 1950s as a technician, a very small cog in the huge state-financed machine working on the UK’s rocket programme for nuclear and space launches. There were other tales, of long overnight drives to the test range in the north of England, and of narrowly averted industrial accidents that seem horrific from our health-and-safety obsessed viewpoint. Sometimes they came out of the blue, such as the one about a lake of highly dangerous liquid oxidiser-fuel mix ejected from an engine that failed to ignite and which was quietly left to evaporate, which he told me about after dealing with a cylinder spewing liquid propane when somebody reversed a tractor into a grain dryer.

Bringing Home A Piece Of History

My dad’s tales from his youth came to mind recently with the news that a privately-owned Scottish space launch company is bringing back to the UK the remains of the rocket that made the first British satellite launch from where they had lain in Australia since crashing to earth in 1971. What makes this news special is that not only was it the first successful such launch, it was also the only one. Because here in good old Blighty we hold the dubious honour of being the only country in the world to have developed a space launch capability of our own before promptly abandoning it. Behind that launch lies a fascinating succession of forgotten projects that deserve a run-through of their own, they provide a window into both the technological and geopolitical history of that period of the Cold War.

![A surviving Blue Streak missile on display at the Deutsches Museum at Schleissheim, Munich. John McCullagh.Jmcc150 [Public domain].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1024px-blue_streak.jpg?w=400)

If you are a follower of British government-funded programmes you might find what followed to be familiar; initial cost estimates of only £50m ballooned by 1960 beyond £500m and headed for £1bn, and the Government pulled the plug following a political scandal. Eventually we bought the American Polaris missile for our Royal Navy submarines, and while it’s tempting for Brits playing what-if to decry that decision, the truth was that launchers such as Blue Streak had become obsolete. Fixed launch sites and relatively long on-the-ground preparation time left the missile vulnerable to Soviet pre-emptive strikes by the early 1960s, and the relative stealthiness of the submarine-launched replacement better matched its opposition. The Blue Streak story wasn’t over as it was recycled into the first stage of the nascent ELDO European co-operative launch effort, but with its initial cancellation died British pretensions toward developing military long-rage ballistic missile carrying rockets.

So We Can’t Make Missiles, Can We Make Spacecraft?

![The Black Arrow first two stages in the background with open payload fairing, in front of that the third stage, and in the foreground the Prospero flight spare. Andy Dingley [CC BY-SA 3.0]](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1185px-black_arrow_satellite_deployment.jpg?w=400)

Black Arrow was only one of a number of UK Government funded programmes that were cancelled in that era, as the economic realities of pursuing superpower technology on minor power budgets in a decade of economic uncertainties became apparent. The future for non-superpowers would lie in collaborative efforts across multiple fields. Launchers such as Black Arrow would be supplanted by the European Ariane platform, military aircraft such as the ill-fated TSR-2 would see their role taken by the Panavia Tornado, and the success of the BAC-Aérospatiale Concorde supersonic airliner would herald the enormously successful Airbus collaboration. Could we have continued with Black Arrow and gone on to become a major launch provider through the 1970s? Probably, but with the inevitable penalty of more cost over-run scandals through which only the strongest-willed Prime Ministers would have retained it.

What Remains Today

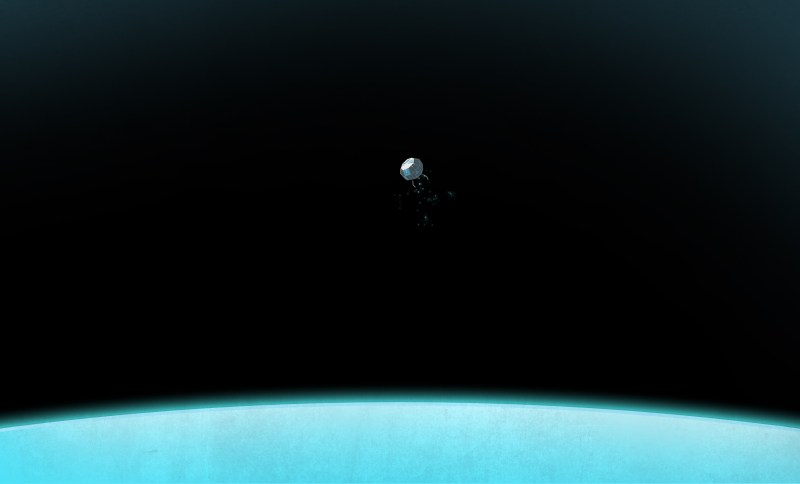

Today Black Arrow and Prospero remain only as a footnote in space exploration history. You will soon be able to view the remains of the first two stages for the cost of a trip to Scotland, but there is more evidence to be found for the curious tourist. The Science Museum in London holds the never-flown fifth Black Arrow and the Prospero flight spare, the Westcott research establishment in Buckinghamshire is now an industrial park, and the High Down rocket test site on the Isle of Wight lies on a public access National Trust property. Meanwhile at the Woomera launch site in Australia there is a park exhibiting a Black Arrow mock-up as well as other pieces of rocketry associated with the range. Perhaps most intriguing is Prospero itself which is still in orbit and which was contacted regularly by the Defence Research Establishment in the years following its launch. It was reported as being still capable of activity in the last decade, and given that its 50th anniversary in 2021 is looming perhaps there are readers who might like to have a look for it on 137.560 MHz. Go on, you know you want to hear that curious piece of space history!

Header image: Geni [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Hmm, where do you buy shoes when your foot is 30mm?

Well spotted. :)

What the site really needs is a link marked “correct” or something that will disappear three or so hours after posting so that comments like mine are unnecessary. An author cannot be a proof reader, that is why people have people that just do proof reading. Sure, you can say it isn’t important enough to bother but mistakes should be corrected.

In my opinion this is a good idea.

Add a hidden link to every word and send a message to the author if a few people have clicked it.

Pet store? Use the chart for sizes. :p

https://ae01.alicdn.com/kf/HTB1IdZ8RpXXXXbTXpXXq6xXFXXXr.jpg?width=1000&height=540&size=222106&hash=223646

Size:

0#-Dog Socks

Paw width: 28mm, Feet length: 34mm, Grip width: 22mm, Socks length: 65mm

1#-Dog Socks

Paw width: 30mm, Feet length: 35mm, Grip width: 24mm, Socks length: 75mm

2#-Dog Socks

Paw width: 31mm, Feet length: 37mm, Grip width: 25mm, Socks length: 85mm

3#-Dog Socks

Paw width: 36mm, Feet length: 50mm, Grip width: 26mm, Socks length: 100mm

4#-Dog Socks

Paw width: 37mm, Feet length:54mm, Grip width: 32mm, Socks length:110mm

5#-Dog Socks

Paw width: 50mm, Feet length: 60mm, Grip width: 35mm, Socks length: 145mm

6#-Dog Socks

Paw width: 55mm, Feet length: 70mm, Grip width: 37mm, Socks length: 150mm

Let me guess… Tories?

as in scandal?

as in cutting funds?

as in going ahead with a launch even though the program was cut?

as in trying to make a working rocket, instead of leaving it to the “Big Dogs”?

yup. Edward Heath was PM – 1970-1974

> airfield in

There’s an extra space here, you can do better.

Thanks Jenny!

I had never heard the story.

And having a blacksmith dad…

awesome!

(Well, mine was a cowboy, and good one at that, but I guess other’s dads often seem awesome)

Somebody’s gotta have a cowboy blacksmith for a dad!

My dad also keeps a herd of cattle, but British style. No horses and Stetsons involved.

That would be “All cattle and no hat.”

So, that First and Second stage look pretty intact, did they have parachutes?

There have been no sustainable projects using this liquid oxidizer because of its volatility. The problem has always been that any contaminates in the fuel system can set it off, like Mentos in Coke. Several navies have used it in submarines and torpedos and those vessels have all subsequently been lost due to accidents with the stuff.

For the curios, this appears to be more info on the satellite (appologies if the link gets screwed up, the satellite is named PROSPERO)…

http://www.pe0sat.vgnet.nl/satellite/sat-history/prospero/

It is sad that UK doesn’t have its own space program anymore. I’m not British, but I think competition in space was very useful while it lasted, from both scientific and unfortunately military perspective.

I sort of think that not having is one of the first steps to humans viewing themselves as human rather than British. It really is time we evolved past random land borders and thought of ourselves as one planet.

Now that we’re leaving the EU, there are plans for the UK to leave the Earth next.

Making deals with Martians is the easiest deal in (off?) the world.

Why should we limit ourselves to only trading with humans?

We can also import food from Jupiter and more pull more great ideas from Uranus.

Dyson is already planning manufacturing facilities on Phobos, assuming he gets the bailout from the UK govt.

And that Wetherspoons guy is opening pubs on Io as the orbit there is 42h, so the very nearly out of date beer he sells on Earth is well within date on Io. They also have easily exploitable employment laws.

Goodbye and thanks for all natural resources, colonies and slaves! And to the EU for all the fish!

Venus’s run away green house effect makes it the hands down winner for farming, I would think. Hot House Venusian Tomatoes anyone?

Is the telemetry format known?

Prospero is quite well documented. There are three different papers on Prospero’s inner workings floating around the Web to my knowledge, and between them, there’s certainly enough information to reconstruct the command system and telemetry decoders. The command system is standard NASA Tone Digital Command, with all of the valid commands listed in one of the three papers I mentioned. The actual command modulation scheme is not discussed in the papers, but I was able to find an old research document that describes Tone Digital Command well enough to implement it with the information the Prospero documentation provides.

As for the telemetry downlink, the actual modulation scheme, data format, and telemetry structure are all documented in the first of the papers I mentioned. You can find them at Mike Kenny’s website, mdkenny.customer.netspace.au/emitters.html. They are linked near the bottom of the page; look for where it says “PROSPERO (1971 Paper, 1973 Paper, 1975 Paper)”. There should be three links each marked “Paper” on that line.

India has a launch programme, North Korea has a launch programme, Iran has a launch programme but the U.K doesn’t, sometimes it’s not a failure of technology but a failure or imagination.

Well, UK contributes 8.8% to the ESA, so you could say that they’re part of the European launch program.

After Brexit? I don’t know. Maybe not so much anymore.

Launch “Comonwealth of Nations’ Space Program”?

India, Iran, and NK have launch programmes because they want to develop nuke ICBMs to threaten other nations with.

We don’t do that shit anymore – in fact, it’s never really been the British way to do war to have doomsday machines. Plus if we wanted to, we’ve got US kit, which won’t be affected by Brexit.

I dare say that Hamburg and Dresden in WWII was that pretty much doomsday machine mentality. Cooked yourselves a lot of krauts there.

India has a launch programme, North Korea has a launch programme, Iran has a launch programme but the U.K doesn’t, sometimes it’s not a failure of technology but a failure of imagination.

https://amsat-uk.org/tag/prospero/

https://space.skyrocket.de/doc_sdat/prospero.htm

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gz-DtGwoqMc

BLACK ARROW, British rockets story, Part 1.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aUJoESpNk_Y

28th October 1971: Prospero, the only British satellite launched with a British rocket

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QifIUAxyHak

Good set of links, I’m amazed so many havent heard of all this before obviously all hidden in plain sight! ;-)

In 1967, I had just completed my second year of engineering and. over the Xmas vacation, had a job in Adelaide with Weapons Research Establishment (WRE), a government instrumentality, which was the city base, we might say, for the range at Woomera. At that time, the British were launching a series of Blue Streak rockets from Woomera. They gave the Aussies the last of the rockets in the series; WRE designed and built a small, sub-orbital satellite (“WRESAT”) and it was successfully launched in November 1967.

My job two month job started In December 1967, and I was one of 200 undergraduates taken on with real projects to do, for 2 months. Of course, the place was hopping, rightfully very proud of itself. Fond memories of those days, of WRESAT and Blue Streak.

Excellent, I didn’t know about WRESAT! Thanks for that.

WRESAT was actually launched on a US-built Redstone rocket. Prospero and WRESAT were the only Woomera Satellite launches. Over a hundred Skylark sounding rockets were launched from Woomera, however, and the bulk of these went well into space before falling back to ground.

If anyone’s interested, I visited the Woomera Missile Park in 2012, here’s my photos – https://www.flickr.com/photos/oflittleinterest/albums/72157630022380545

Great pics! I love the way they mounted the bombs! Can you name any of the objects?

Half the ham radio satellites in orbit seem to be built by the University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, however presumably they aren’t technically LAUNCHED by Britain – they hitch a ride with someone like NASA or Roscosmos or presumably ESA (the obvious successor to any Brit space program, until Brexit)?

Yes Surrey Space does absolutely tons of satellites not least the Galileo satellites that everyone is on about!

https://news.sky.com/story/uk-built-prime-rocket-to-become-first-to-blast-off-from-britain-11630945

Can’t see a mention of the national space center in Leicester.

There’s a blue streak rocket there on display as well.

https://spacecentre.co.uk/

Worth a visit if you’re in the area.

This project gets a mention in “Backroom Boys” by Francis Spufford (excellent book BTW), his version suggests that America wouldn’t sell us their missiles until we’d proved we could do it ourselves anyway or some such political faffing about…

A shame it got cancelled but the country was going to the dogs in those days, not like the strong & stable times in which we now live. Um.