I am a fan of the saying that those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it. After all, humans have been building things for a number of centuries and we should learn from the engineers of the past. While you can learn a lot studying successes, sometimes — maybe even most of the time — we learn more from studying failure. The US Navy’s Mark 14 torpedo certainly has a lot to teach us.

The start of the story was the WWI-era Mark 10 torpedo which was fine for its day, but with faster destroyers and some additional data about how to best sink enemy ships it seemed necessary to build a new torpedo that would be faster, carry more explosive charge, and use a new method of detonation. Work started in 1931 with a $143,000 budget which may sound laughable today, but that was a lot of coin in the 1930s. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about $2.5 million.

Changes Needed

Data from the earlier war indicated that you got the most effect by detonating explosives underneath a ship. This was especially true since warships were adding torpedo blisters to absorb strikes along the hull. With a contact fuse, you would tend to explode on the hull somewhere along the perimeter of the ship’s envelope and a ship — especially one with blisters — was more likely to survive the strike.

Contact triggers were out and instead the torpedo would read the change in the magnetic field caused by the enemy ship’s hull and detonate under the ship, splitting the target in half. Unfortunately, the Earth’s magnetic field varies based on location and this made the new detonators unreliable. Some estimates are that the torpedo had at least a 50% fail rate in combat. In 1942, out of 800 torpedoes fired, 80% failed to do their job.

In the 1930s, this torpedo was as complicated as you could get. Clearly, you’d want to test this new design pretty exhaustively, right? The cost of the torpedo and some political wrangling thwarted testing that would have uncovered many problems. Cutbacks meant there was only one company making the torpedo, at a slow rate, and with little oversight. In 1937 the Naval Torpedo Station in Newport, Rhode Island employed 3,000 workers working three shifts and still only produced 1.5 torpedoes per day.

The the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance not only produced a bad design but then failed to test. The real root cause for the high failure rate was this lack of testing.

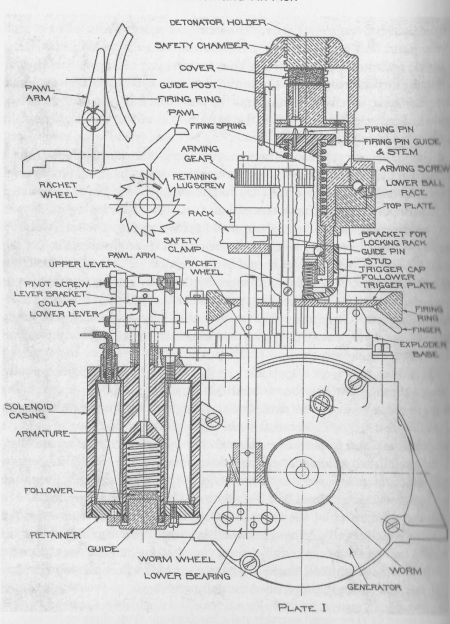

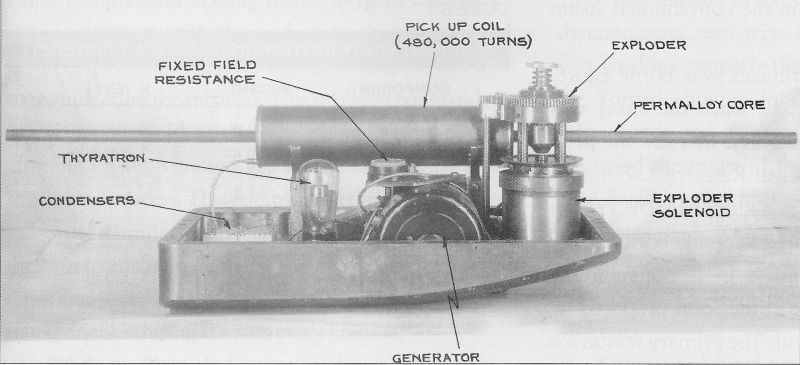

Complex Hardware: The Mark 6 Magnetic Influence Detonator

The Mark 14 steam torpedo had the option of using a traditional contact detonator, or the magnetically triggered Mark 6 exploder, which was a marvel in its day.

Paradoxically, the Mark 6 was so secret that its manual was never printed and the original was locked away in a safe where it didn’t do anyone any good. It derived from German magnetic mines and that might have been part of the motivation for the secrecy. Oddly enough, you can read some of the manuals online now. The Mark 14 maintenance manual is pretty interesting.

Despite the promise of the new technology, in war crews noticed the new torpedoes were either exploding too early or going too deep. The Bureau of Ordnance dismissed reports that the torpedoes were not effective, blaming the crews for not operating the devices correctly.

That Nobody Can Deny

The little official testing conducted before production was done with a light dummy torpedo. When post-production testing finally took place they showed the torpedo was running deep. Naturally the dummy didn’t sink as far as a fully-operational torpedo in the previous tests.

The little official testing conducted before production was done with a light dummy torpedo. When post-production testing finally took place they showed the torpedo was running deep. Naturally the dummy didn’t sink as far as a fully-operational torpedo in the previous tests.

Faced with direct evidence that the torpedoes were failing, the Bureau finally conceded there was a design problem with the depth mechanism. It would turn out that in addition to the depth problem, the magnetic detonator was too sensitive. There was a backup contact detonator, but it used a firing pin that often failed when it hit enemy ships. That was odd since the system had worked on earlier torpedoes.

The Mark 14 was faster, so striking a ship involved more force than before and it was enough to bend pins in the firing pin block. The designers apparently noticed this early in the design and added stronger springs, but as the torpedo’s maximum speed increased the new springs were not enough and there was no further testing.

One quick fix for the firing pin problem was to machine down lightweight aluminum alloy to make a stronger and lighter firing pin. Oddly enough, some of the material they used was from Japanese planes shot down over Pearl Harbor.

Passing the Buck

This is a sad story that has been repeated many times since then. Budget and schedule pressures short cut technically sound judgment. Then no one wants to admit that there is a problem because that would look bad. As engineers, we should sound the alarm when things are not done right and management should be willing to take a hard look at the cost of doing it right versus the cost of having to redo it later.

The hero of this story, by the way, is Charles “Swede” Momsen. He was an engineer who had proposed the submarine rescue chamber and developed the Momsen lung, which was not entirely successful. When the commander of the Southwest Pacific submarine fleet decided to solve the problems with the Mark 14, he turned to Swede. He carried out the tests that should have been done during development.

The other heroes are the crews that managed to work around these problems as best they could. Despite the Bureau ordering the exploders to have painted screw heads to deter tampering, crews found matching paint and removed them anyway. We’ve seen a lot of ingenuity like that during war. Not the least, of course, is hacking foxhole radios.

We know not everything we work on is a life or death project. But when people do depend on your work to either behave or not behave in a certain way, saving money on testing often goes badly in the worst way. That’s the lesson of the Mark 14, the Mars Climate Orbiter, autonomous vehicle crashes, or a failed software update bricking devices.

Going Deeper

As you might expect, this story has been told many times. I liked [Drachinifel’s] video about the history of the Mark 14. Some people don’t think the real impact of the torpedo issues were as great as reported, but I imagine if you were on a sub crew effectively firing blanks, you might not agree. [Military History Not Visualized] has an interesting video about the real impact of the failure on the course of the war.

Image Sources:

- Main Image: Cliff on Flikr (CC-By-SA 2.0)]

- Thumbnail image: Cliff on Flikr (CC-By-SA 2.0)]

Fascinating story, thanks! I’ll note that testing errors killed Mars Polar Lander, not Mars Climate Orbiter. (The latter was the one with the unit-based communication failure.)

Arguably any software bug that “goes into production” can indicate a testing failure.

This problem was resolved in part in 1944 by the Mark 10 contact-magenetic TBM to surface torpedo–whcih did much damage to the Japanese Navy in early 1944. In collaboration with Einstein, R. Alpher developed the new Mark 10 Contact-Influence exploder which was enormously successful. I wrote two articles on this it he 2010-11 Submarine Review.

Testing does not change anything!

Only fixing bugs gets rid of bugs.

I’ve worked as a software tester and as a software test manager.

You can have tons of bug reports with the best problem descriptions but if your Product Manager says that the ship date has arrived and therefore the product will be shipped then even the best testing does not help.

Do managers want to ignore test results?

Yes! All the time!

It makes them look bad, it creates schedule issues and other problems. Project and Product Managers usually have little incentive to react on test results.

The whole QA is sick or on vacation or whatever? Great!

I watched Drachinifel’s video some time ago and it really liked it.

History is repeating itself all the time.

One expensive example:

In 1997 the Mercedes-Benz A-Class disaster started with a Swedish journalist reporting that the car rolled over during the Swedish Elk/Moose-Test. Mercedes had tons of internal test results that the center of gravity was too high and the car was unstable in such situations. Fixes ware expensive and therefore the product was shipped as is. Later on (after negative media attention) they fixed the problem for good and the car became a success.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moose_test

Measuring “on time delivery” or “project budget” is easy. Measuring quality is difficult and sometimes only possible long after the product has been shipped. With software there is a tendency to deliver now and fix things later on with various bug fix releases. But that’s the problem of someone else …

And getting pregnant doesn’t change anything, only giving birth…

While not sufficient to resolve the issue, lack of testing in the development phase severely retards bug fixing in the development phase because… wait for it…, bugs are not found.

Testing and fixing bugs are two different things.

Even after getting pregnant you have to decide if you want to give birth.

With the difference that pregnancy leads more naturally to birth then test results lead to a project budget for fixing bugs.

People who don’t work in the industry often assume that test results automatically lead to problem solving activities but there is no direct connection.

The torpedo was not properly tested because the company who manufactured the torpedo was afraid of the test results and many people in the navy as well.

If you don’t want to fix problems anyway then you can skip testing.

“If you don’t want to fix problems anyway then you can skip testing.”

Reminds me of advice I got in flight school.

if you have to do a forced landing at night, first turn on the landing light. if you don’t like what you see, you can turn it back off.

Did they tell you the number of landings should always equal the number of takeoffs?

Gregg:

The number of landings always matches the number of takeoffs. The real question is if all of them can be entered into the logbook.

You go try getting (being) pregnant for 2 years without giving birth and see if it changes anything.

I do not mean the trying part, but the being.

Testing uncovers issues, then you must have the Engineering support to analyze those results and then even more support to improve design as the results of those tests.

Testing is just the beginning. If they didn’t have the money for proper tests then they surely did not have the money to follow through with the rest. Maybe the designers knew this?

I worked for a short while for a company in product development where the management took their most innovative engineers and asked for products that were totally unique, would completely capture the market and had only sketchy scope and virtually no input from customers.

Well, all of that is okay as with a few exceptions is kind of the nature of the beast.

Then, after budget, scope and milestones, general outlines, etc., were on the PowerPoint, non engineering management would have a meeting, generally to slash development budget and typically cut the timeframe by 1/2 to 2/3.

About 1/2 way into the available time they would use concept artwork to generate brochures and distribute to trade shows.

When it started to get close to *prototype* (untested) delivery, they started promising immediate shipdates.

Any time an engineer would bring up that there are many, many steps between handbuilt prototypes and having a real product, all the engineers would be brought in and yelled at for not inventing something sooner and the engineer who brought it up would be either fired or pulled from the project.

Eventually this was a competency filter for the department where the only ones who would stay in the department were the ones who, for one reason or another, put up with this.

Eventually their product development degenerated into white labelling competitors equipment. Even with this they would set up multi month project management processes to get their logo placement “just right” and scrubbing the technical documentation to make sure their customers couldn’t identify the product, notwithstanding the customers are almost always smarter than they were given credit for.

At the end not a single engineer who had ever once in his life ever touched a soldering iron or written a function was on the staff. There were engineers on board but I don’t have any idea how they got there. Many of them had EEs and MBAs and were very astute politicians.

For the last year and a half, I’ve been on a crash course in a safety certification system.

The model for the engineering discusses verifying design at various stages. One of the cornerstones of verification is testing.

I don’t know what mechanism provides the ‘teeth’ for automotive companies violating things like ISO26262 but it sounds like there is an enforcement issue.

And that really seems to be the key here, there must be a system of checks and balances which does not depend on the consumer and results in enough loss of profit to make doing the job right the first time look attractive.

As for software, it seems to me that it is practiced as a craft, not as an engineering discipline. The lack of a design decoupled from an implementation impacts testing too as part of testing becomes not just verifying the implementation is free of defects, but also the design (and the push-back seems to come most strongly when testing uncovers defects in the ‘design’ of the program).

All this reminds me that “the rules of safety are written in blood” and it seems that a periodic refresh is required for the current generation to understand the price past ones payed.

The semi-fictional book “run silent run deep” has a large section about how the torpedo problems caused problems for the subs and how they were addressed in the field.

“In 1937 the Naval Torpedo Station in Newport, Rhode Island employed 3,000 workers working three shifts and still only produced 1.5 torpedoes per day.”

Assuming that there’s an hours worth of breaks per shift, that’s 63,000 person hours – per day. That’s the better part of one person’s total career – per day.

I’d love to see a breakdown of what they were doing – C. Northcote Parkinson would have been in awe.

https://www.economist.com/news/1955/11/19/parkinsons-law

It looks like it was a whole weapons development complex – everything from the torpedoes to air drop/launch trials, guidance & propulsion systems and on and on. That production number may have referred to prototypes.

https://www.public.navy.mil/subfor/underseawarfaremagazine/Issues/Archives/issue_07/newport.htm

I am wondering what they did with all those half torpedo’s at the end of the year.

Look for the large magnetic response 1/4 mile offshore.

Winding 480 000 turns by hand …

Mostly machinist cranking out the tons of mechanic control system

I think you’re imagining a military with more tooth than tail. Admin and support. Did you know prison camps had accountants? My father was one, at a POW camp in New Jersey. Admin and support.

You gotta respect any diagram that points out a device called the Exploder.

Reminds me of the Claymore mine’s “Front Toward Enemy”.

+1

The Chinese version is superior. It says “This side toward enemy”. In Chinese, of course, but less ambiguous: “Which side is the front again?”

Tell that to the script writer(s) in one of the Resident Evil movies. They had a Claymore blowing up in all directions.

Well, the Claymore throws most of its ball bearings in the “front” direction.

Would have been ironic to print “Front Towards Enemy” on the backside of the mine.

The instructions are still valid…

Yeah, where you can read it safely! That occurred to me. It was probably considered too expensive to put words on both sides, like “This is where you want to be” and “If you can read this … you’re screwed.”

Actually the Claymore has a rear danger zone as well, you’d best in a foxhole if you command detonate it.

large arrow labelled “enemy”

Ah hell that’s nothing, the Royal Navy had a whole submarine called Exploder!

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Explorer_(submarine)

didn’t Microsoft have a product called Internet Exploder?

And Ford had similar named SUV known for exploding tires/tyres!

B^)

Yeah, but only if it actually explodes.

I was going to leave a link to the Drachifinel video! It’s probably one of his best, other than the indepth video series on the first and final voyage of the Bismarck, and the video on the Channel Dash.

I forget which John Wayne movie covered this story (with artistic license).

Here it is…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Pacific

“Torpedo Blisters” is the name of my next band

Cool, cool, cool….. I’m taking “Exploder Solenoid” then.

Was a sad day when they moved the Mark 48 production out of Cleveland and shut the entire plant down. :(

You forget the “voyage of the damend” Ok, not very technical, but tragically amusing.

https://youtu.be/9Mdi_Fh9_Ag

In the thumbnail photo, I pity the guys that have to keep polishing that brass nose cone!

Well it gets lonely at sea, sometimes you have to “polish the brass nose cone”.

I have a gyroscope for a Mark 14 torpedo. You can see it in the manual at page 80. Amazing piece of work. Spin it up to speed with air an the thing will run for a long time. Considering how much delicate work went in to each ones I can believe they only made 1.5 a day.

I think I remember seeing those in the surplus section of hardware classifieds into the 90s. It did cross my mind to buy one, for I think $180, when DARPA did one of their very first autonomous vehicle challenges.

After he was asked to solve the problem of the faulty Mk14’s, Swede Momsen came up with the idea of a submarine going out and firing a bunch of torpedos at a cliff wall to see if they’d fail. The second torpedo fired failed to detonate, and he personally dived overboard and secured the damaged torpedo (with live ordanance still in it) so that it could be retrieved and researched to discover what the problem was.

This was after his submarine rescue device rescued the sailers aboard the Squalus, but before he discovered the practice of carrying gunpowder in silk bags was dangerous.

Amazing what he achieved.

A couple days ago I was reading about the https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_50_torpedo It’s weird because its propulsion system is sulfur hexafluoride and lithium metal, and the products, elemental sulfur and lithium fluoride, take up much less volume than the reactants, so they don’t have to worry about trying to vent to high pressure water through valves, and no bubbles during operation.

The Americans should have bought Long Lance torpedos, those things were great!

Except when the ship/submarine carrying them had a fire onboard…Those that survived such an incident usually did so only because they dumped them overboard.

The United States Naval Undersea Museum located at Keyport, Washington is a great place to see this and other naval ordinance (going back prior to the Civil War) along with awesome presentations. Also has a lot on undersea vehicles.

We visited that.

At the time, a family of raccoons were inside ALVIN.

A few comments. Shipping things that do not work seems to be common, and worse when the parts are sub contracted. The subs often have a thin layer of paperwork to go through until the correct one is identified, and you would be amazed at how often the contractors never dig back. At one place I worked we had a production manager that would ship boards with major parts missing “Will will meet the deadline, It will look good on paper” and I was always expecting to see truckloads of those boards come back or that contract end. In my tenure there neither ever happened. Go figure.

On a big project you also get into the thing with engineers. Engineers are rarely ever satisfied and are always worried something will go wrong. Something can always go wrong. The idea is to build enough and test enough to find the sore spots so you can say, if all of the pieces are right, this will function. But get something that takes a bunch of engineers, and I am not picking, but it is hard to ever get the final “go”. I think this to some extent leads management hard pressed to decipher normal background grumbling from real issues. As I stated above, some managers are not saints either..

One other thing to ponder, if the failure rate is 50%, that sounds high, but if the success was sinking the enemy ship, and it was the only technology capable of doing that at the time, perhaps the failure rate was not so bad. Have a gun that goes off half the time or point your finger and go bang… I would take my chances with the gun.

Don’t forget that until the torpedo was fired, the chance was big that the submarine was not detected.

However, if you fire a torpedo at a destroyer filled with water bombs, and it doesn’t go off, the enemy will know you are there.

Then you’ve got some VERY angry nazis coming for you and thanks to the bubble trail they have a pretty good idea of where you’re located.

If you hadn’t had the torpedo, you wouldn’t have been out there in a submarine anyways.

It was kinda their only point.

Recon, first half of the war they could have kept an eye on stuff out of range of aircraft and radar, and kept close tabs on dangerous units when it was cloudy.

Radar was rudimentary in the early war years.

IIRC, IJN Yamato had one of the first.

Bubble trail from what, exactly?

Exhaust gases from the engine,

and possibly propeller cavitation?

The Germans and Japanese had torpedoes with much lower failure rates, and I think the actual failure rate of the Mark 15s with the magnetic detonators really was between 80% and 100%. It did get better when the Navy adjusted the depth setting upward and when the crews bypassed the magnetic detonator.

Also as Laurens points out, it wasn’t like a sub could fire several torpedoes with impunity to increase the chances of a hit. (Maybe on a moonless night that would work?). Once the first torpedo was spotted, the target would begin evasive maneuvers (stop being broadside to the sub by turning toward you) and possibly start dropping depth charges on you. Torpedoes fired at a ship coming straight at the sub generally didn’t a) hit, and b) do much damage, on the off chance that they glanced off the narrow hull and exploded. So the best choice for a lone submarine was generally to fire and dive.

The Germans had torps that went boom, but early in the war had tracking and targeting problems I think. They were delighted with Allies deciding to convoy shipping, because that meant they could fire a torpedo and hit something. They could hit single ships if they were going slow enough and they got the exact right angle on them, but unless they could do that on hydrophone, they risked the periscope or snorkel getting spotted by an alert crew as they popped up to get fixes on speed and course. Their torpedoes got better also though.

I work at Naval Torpedo Station in Newport, Rhode Island successor’s, NUWCDIVNPT as an engineer. While this story is generally correct, it is vastly over simplified. Research can give more details.

“Some people don’t think the real impact of the torpedo issues were as great as reported, but I imagine if you were on a sub crew effectively firing blanks, you might not agree”

I think if you’re firing blanks you’d definitely be complaining that the torpedo lacks impact…

Ask the European Space Agency about the importance of testing and the first Ariane 5 rocket.

Or NASA and the Hubble mirror?

I’ve read about this previously in great detail in the past. Submarine commanders: “These torpedoes don’t work!” Bureaucrats: “You’re not using them right.” Considering how many lives were probably lost due to an inability to sink enemy ships and putting submariners in harm’s way with no results in wartime, those high ranking military responsible for not listening to those in the field should have been court-martialed and any high level civilians involved imprisoned, making sure this was widely known after the Mk14 problems had been fixed. This might have lead to people f’ing listening to the real experts – those actually using the weapons.

For an exhaustive detailing of every submarine war patrol in WWII, go find Silent Victory: The US Submarine War Against Japan by Clay Blair Jr.

Nearly every single Mk XIV torpedo fired in anger failed. Flights of 6 bow tube torpedoes, fired at near point blank range (300m or less on some occasions) failed to score. Blair paints a sobering picture of the administration’s failure. Numerous requests were made for live fire testing and all were denied; torpedoes were extraordinarily valuable and not a single one was to be “wasted” in a live-fire test. Many a skipper was demoted because of poor performance, lack of “aggressiveness” or wasting torpedoes. Many more cracked up under the stress.

Blair’s unabashed opinion is that, certainly early on, misallocation of submarine forces in the war against Japan, coupled with the laughably ineffective Mk XIV, resulted in almost no impact on the war itself.

There is also a fascinating side story about the cryptography involved in monitoring Japanese shipping lanes.

A fascinating read.

My Uncle served the first phase of the war on SS-171.

He rarely spoke of the war, but the one time he opened up, he bitched about the dud torpedoes.

I was a torpedoman (TM) aboard a nuclear powered missile submarine in the mid-70s. We had quite an inventory of modern and older torpedos aboard, but about half of those weapons were war-proven World War II built Mk.14s. I wish that I had one of the green hard bound log books that accompanied each Mk. 14. The weapons were almost 21 feet in length and 21” in diameter – big, powerful, and fast. Equally important, they were immune to electronic and electromagnetic countermeasures. The Mk. 14 remained in use until all torpedoes were replaced by the Mk. 48 series in use today.

I should add, the Mk. 14 was initially held back from its true capabilities due to a faulty magnetic detonator, weak backup contact detonator, and improper depth setting. When Admiral Lockwood stepped up and insisted on local testing in Pacific waters, the faults of those features were revealed and removed from existing weapons and not used in newer weapons. The end result was a a clean, simple, highly effective design with no frills. A design that served the US Submarine Service well from the last half of World War II – until about 1980.