Over the years we’ve brought you many examples in this series showing you technologies that were once mighty. The most entertaining though are the technological dead ends, ideas which once seemed as though they might be the Next Big Thing, but with hindsight are so impractical or downright useless as to elicit amazement that they ever saw the light of day.

Today’s subject is just such a technology, and it was a serious product with the backing of some of the largest technology companies in multiple countries from the late 1980s into the early ’90s. CT2 was one of the first all-digital mobile phone networks available to the public, so why has it disappeared without trace?

The Future’s Cordless, Not Cellular!

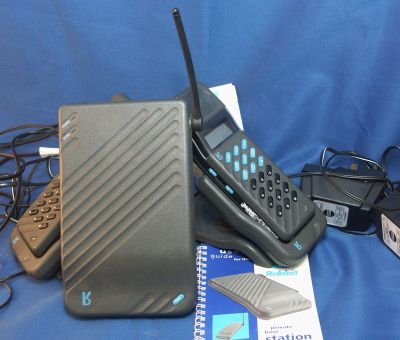

The idea was simple: to bridge the gap between a domestic cordless telephone and a mobile phone, by supplying a handset that could not only work with your base station at home, but also make calls from commercial base stations when you were out and about. Instead of a bulky brick of an analogue cellular phone you’d sport a svelte and stylish handset, and place important calls while striding across a railway station concourse on your way to high-powered business meetings. It was intended as a replacement for the pretty awful analogue cordless phones of the day, and here in the UK it was an idea tried out by multiple companies and the IEE Review foresaw a bright future for it.

The technology was for its time quite revolutionary in a consumer product, ADPCM-digitised 32 kbit digital data streams multiplexed on carriers in the range of 864 to 868 MHz. The handsets were not powerful at only 10 mW output, which was probably the main reason for their claimed 100 m range from a base station. Because they were a fancy take on a cordless home phone rather than a fully-fledged mobile phone their users had to authenticate with each new base station by typing in a PIN, this shortcoming meant that they could only receive calls through the landline on their owner’s home base station. There was no automatic handover between adjacent base stations, so it was not a cellular system.

An Exercise In How Long Defunct Signage Can Stick Around

Given that it received national publicity, why did each company in turn try their luck in the market only to fail? In the first instance the handsets themselves were significantly expensive, in the region of £200 (over $300 in 1990 terms), which put their cost well out of reach of those non-mobile-owning customers who might be tempted by a cheaper alternative. Then on top of that there was a monthly subscription and call charges, further increasing the costs.

The real killer though was that a base-station-dependent network faced an impossible task in providing enough coverage to ensure that its users had a chance of being somewhere they could use it. They could be found in public places such as rail and bus stations, motorway service stations, and shopping centres, but even a roll-out to small convenience stores could not provide the required penetration. The best-known of the networks, Rabbit, was at its peak while I was a student, and though it was the time when a few students were already sporting mobile phones, in conversation with friends there’s not one of us who could remember knowing anyone with a Rabbit phone. Not encouraging for a network intending to be a cheaper alternative to a mobile phone.

Perhaps if the handsets had been much cheaper the system would have brought in more customers, and the base station network would have expanded to the point at which it became a more attractive proposition. As it was the arrival of GSM mobile phones brought in a similarly-priced but just better digital system which offered universal coverage and incoming calls, and by the end of 1993 the network was dead. The Rabbit base stations and handsets could be found from surplus suppliers for the rest of the ’90s as slightly unusual cordless home phones, but otherwise it survives only in a handful of decaying pieces of signage that can still be seen from time to time as you travel round the UK. [Ringway Manchester] features some of them in the video below the break.

There’s a footnote to the CT2 story in the European DECT digital telephone system. This was intended to be the replacement for CT2 and has the specification of a fully-functional 3G cellular phone system including a data layer as well as its common use as a domestic cordless phone, but never achieved that potential. The networks and manufacturers had had their fingers truly burned by cordless handsets, and wouldn’t be looking anywhere but GSM for the rest of the decade. Today one of the very few places you’ll find a functioning public DECT mobile network is in our community, in the form of the networks at European hacker camps provided by Eventphone.

Did any of you have a CT2 phone? Was it better or worse than our assessment? Tell us in the comments.

Header image: Jmb, CC BY 2.5.

I was wondering why DECT had a million features nobody implemented. DECT-based wifi might have been interesting.

This might interest you: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Net3

Fun fact : Dect is still used by clearcom for their wireless coms.

Wireless microphone systems (RevoLabs and Shure MXW), ALS (Williams AV), and the ubiquitous Poly (Pantronics) wireless phone headsets have been playing in DECT as well.

“The idea was simple: to bridge the gap between a domestic cordless telephone and a mobile phone, by supplying a handset that could not only work with your base station at home, but also make calls from commercial base stations when you were out and about.”

My ATA has the ability to link in a cell-phone via bluetooth. Also WIFI-calling could be said to be a modern version of CT2.

Few year later SENAO start to make similar phones, but with range of 1-3 km. Base station and phones have 5-10 Watts radiated power.

The problem with CT2 is that it worked right in the ISM frequency which limits the allowed power and/or transmission time to an absolute minimum, because it’s a license-free frequency. It was basically a fancy walkie-talkie with the caveat that anything could interfere with the transmission.

There was a system between that and the Rabbit one described, can’t dig the name of it out of my brain right now. Anyhoo, it was supposed to give 500m urban range, and it actually got in the range of “cheap”, which is probably low end cellphone plan money these days. I was considering getting one for a few months, as I knew there was a base within 500m of my house, so it could have worked at home. Also, they pushed it out to convenience stores as the prime basis of the network IIRC, and many of them had it, it seemed they almost had complete coverage of the city. BUT as I dragged my feet I heard rumors that they’d overstretched and soon the signs and the “radome” antenna covers on the sides of the stores started to disappear, so was probably a dodged bullet really.

Yah know, I think it was the Mercury Callpoint mentioned here, but I remember a kinda two line swoosh mercury logo being the prominent branding I think… http://www.cntr.salford.ac.uk/comms/telepoint.php.html

It has kinda come back again in functionality… you can get a phone or tablet with no cellular subscription and put a VoIP app on it, (Fongo, google voice etc) and make and receive calls where or whenever you find a public wifi hotspot. (By the way check if your credit card gives you subscription to hotspot networks)

My friends and I both had these for home use. The quality of the audio was pretty good, much better than other cordless phones of the time. I also remember seeing these with credit card dongles on airline flights for duty free… but after a few years they just wouldn;t work anymore. Shame!

My father (in the Netherlands) had a “Greenpoint” phone which apparently was CT2-based.

It worked the same: call-out only on public station (train stations and gas stations, but also “Interliner” (express bus) stops). At home it worked like a normal cordless phone.

The phones were originally called Kermit but the licencing costs from Henson proved too high so it was renamed Greenhopper.

The more expensive models had a semaphone function so you knew when you were called and then could pull in to a gas station.

We used it at home for years, it’s handset was very small and light, and had very good battery life compared to the other DECT unit we had. Unfortunately my father threw it away a few years back.

Oh, flashback time! Worked on the Ferranti Zonephone as a callow youff and had a couple as my home cordless phone. Bet they are still in the attic! They had a neat UI.

Not in Chadderton?

Nope, it was at PA Consulting, Melbourn, UK.

Big boss in Kuwait in the early 90s (a couple years after the invasion) had a homemade version of this: a base station radiophone at the job site, one at the office, and one at home, and a single handset that would end up being in range of at least one of those. When it was in range of two, someone at one of the base station would manually hang it up as necessary.

BTW in the UK you might get some base station kit turning up at ham fleas and car boots. Greenweld.co.uk was flogging off a bunch of it as surplus a good few years ago, so it got into the hands of “the public” that way. If it interests you most desperately, I guess you could give Greenweld a bell and ask if there’s any still lurking in corners of the warehouse.

We had something similar (if not exactly the same technology) at roughly the same time in Australia, but I’m not too sure if it every actually took off beyond a trial in the Sydney (and ISTR Brisbane) CBD. I do rember the “phonepoint” signs on some buildings in Sydney and our newspapers running articles on it. Unfortunately almost impossible to web-search about because of its name and quick failure/discontinuing.

We had the “Kermit” in the Netherlands which used similar tech, also outbound only when not used at home, and only at certain hotspots.

The handsets were a lot thinner/lighter though.

1994 Neal Stephenson “In the Kingdom of Mao Bell” article in the Wired talks about actual contemporary CT2 deployment in China/Shenzhen. I especially like the magazine cover tag line “Snow Crash’s Neal Stephenson Visits Shenzhen”

Article text: https://www.wired.com/1994/02/mao-bell/

Full magazine scan: https://archive.org/details/eu_Wired-1994-02_OCR

“Even people who carry cellphones carry pagers, which confused me until I found out that most of the cellphones I was seeing aren’t really cellphones at all; they are CT2 phones, which are cheaper and operate over a much shorter range. On a CT2, you can call out but you can’t receive calls, so you have to carry a pager. To cover a metropolis with CT2, tens of thousands of base stations would be needed. Coverage in Shenzhen is still spotty. When you see half a dozen young men loitering on the front steps of a building shouting into their prawns, you know there must be a CT2 station inside.”

My husband, John Cummings was the MD of Ferranti Creditphone. I remember going to Leicester Square in London to try out the Zonephone there. I still have memorabilia. The head office was at Sunlight House, Macclesfield.

Hi Margaret, I remember John well. A great leader who successfully took a small group of men and women, pre CT2 licence, to a complex multi million pound business running from a couple of large wooden cabins in the grounds of Ferranti Gem Mill. I and my colleague Geoff, in our suits and ties, went up the ladder to install the Leicester Square base station.

I had a couple of home base stations bought after the rabbit network closed down and the electrical shops (Dixon/currys) had stopped selling them, I seem to remember I bought them from a supplier via CIX in the UK and I had at least 3 or 4 handsets (probably still have them in the loft)

They did still work for incoming calls last time I used them, but outgoing Lines needed to support pulse dialling as DTMF was not supported, ,guess that’s why I stopped using them.

In around 1995, the office I worked in was planning to move to another nearby larger space, and the was a 2 week period when we were half-way moved, using both locations.

for whatever reason, BT couldn’t wouldn’t provide a interim service at the new location (without a massive cost) so for the couple of weeks until we could get the nortel PBX physically moved over we ran the new building using my 2 rabbit base stations as extensions and had wireless coverage the 100metres or so across the carpark to the new building.

They worked flawlessly, and service was maintained.

2 lines doesn’t sound like many, but this was an office of about 40 people mostly engineers, I think we had 8 BT lines on the PBX and 30 or 40 internal analogue extensions.