When we picture the Medieval world, it conjures up images of darkness, privations, and sickness the likes of which are hard to imagine from our sanitized point of view. The 1400s, and indeed the entirety of history prior to the introduction of antibiotics in the 1940s, was a time when the merest scratch acquired in the business of everyday life could lead to an infection ending in a slow, painful death. Add in the challenges of war, where violent men wielding sharp things on a filthy field of combat, and it’s a wonder people survived at all.

But then as now, some people are luckier than others, and surviving what even today would likely be a fatal injury was not unknown, as one sixteen-year-old boy in 1403 would discover. It didn’t hurt that he was the son of the king of England, and when he earned an arrow in his face in combat, every effort would be made to save the prince and heir to the throne. It also helped that he had the good fortune to have a surgeon with the imagination to solve the problem, and the skill to build a tool to help.

The Prince

Henry of Monmouth, the future Henry V, was born in 1389 in Wales. His father, Henry Bolingbroke, was cousin to the current king, Richard II, whom he deposed and imprisoned in 1399. Styling himself Henry IV, this put his son Henry, now the Prince of Wales, into the line of succession as heir apparent. As such, great effort was put into grooming him for future kingship, including extensive military training.

Prince Henry’s training was very quickly put to the test at the Battle of Shrewsbury, where King Henry’s men faced the rebel forces of Lord Henry “Hotspur” Percy. The battle marked the first time that English archers faced each other. The English longbow was a terrifyingly powerful weapon, with a draw of 90 to 100 pounds or more; longbows found aboard the wreck of King Henry VIII’s flagship Mary Rose were found to have draw weights of up to 160 pounds. Such a bow would require astonishing upper body strength to draw properly, so much so that the skeletons of English archers show considerable overdevelopment of the bones of the left arm and wrist, as well as the fingers of the right hand.

The Weapon

An English longbow of the era typically was about six feet long, although that varied with the stature of the archer. Arrows typically had thick shafts of poplar, ash, beech, or hazel about 32 to 36 inches long, fletched with goose feathers. Shafts could be fitted with a variety of arrowheads, each specialized to different needs. But the most common warhead at the time was the bodkin point.

A bodkin point was designed to defeat plate armor. Accounts vary on its effectiveness, and modern testing is somewhat equivocal. But the shape of the head, with its square cross-section and sharp edges, was clearly designed to cut through sheet metal. Like most mass-produced metal objects at the time, bodkin points were made from wrought iron. Even with hardening and tempering, this would have left the point too soft to penetrate into the steel plate armor that was becoming more common, but there are historical accounts of bodkin points being “steeled”, which may mean that they were case hardened. This would have been done by wrapping a number of points in charcoal and heating them in a forge to carburize the metal.

Arrowheads of the day were forged with sockets, allowing them to be fitted to the end of a shaft. Methods for attaching the head to the shaft varied; some were glued with hide glue, some were pinned with tiny nails, and others were simply friction fit into the sockets. The latter seems to have been the case with the arrow that found Prince Henry, a stroke of good fortune that would end up helping save his life.

The Battle

The Battle of Shrewsbury was fought on 21 July 1403. Shortly before dusk, King Henry gave the command to attack the Percy forces, and the battle was on. Prince Henry, protected by plate armor and leading his men on the left flank, advanced uphill into the rebel line. The young prince raised the visor on his helmet for a better look at the battlefield, and as luck would have it, an arrow caught him in the face. The bodkin point drove into his left cheek, below his eye and just to the side of his nose. Miraculously, the arrow stopped with about six inches of the shaft embedded in the prince’s face; given the power of a longbow shot at close quarters — easily enough to punch straight through a human skull — it’s likely that the arrow that found Henry was deflected by a shield or someone else’s armor, spending the majority of its kinetic energy in the process.

Despite the agonizing wound, Prince Henry refused to leave the battlefield and kept fighting for three more hours, until Henry Percy suffered a wound ironically similar to Prince Henry’s; when Percy raised his visor to get a breath of fresh air, an arrow, this time unmolested in its flight, found his gaping mouth and killed him. Only then was Prince Henry rushed from the battlefield to nearby Kenilworth Castle, in an attempt to save his life.

The Injury

The fact that the prince was not cut down instantly was a stroke of amazingly good luck. The base of the skull is rich with major blood vessels that supply the brain, important cranial nerves that control basic bodily functions, and the top of the spinal cord, where it exits the skull via the foramen magnum. That the bodkin point threaded between all of these vital structures and lodged itself in the thick, tough bone at the base of the skull, and did so little damage that the prince was able to keep fighting, was nothing short of miraculous.

The royal surgeons knew, however, that the arrow had to be removed. Standard practice at the time was to push the arrow through in the direction that it was going, but being lodged in Henry’s skull, the only option was to pull it out. When surgeons tried this, though, the shaft came free from the arrowhead. It’s not clear if the shaft broke or if it pulled free from the bodkin socket but either way, it left the arrowhead lodged in the prince’s skull at the end of a deep, inaccessible wound.

The Surgeon

At this point, surgeon John Bradmore was sent for. In those days, being a surgeon did not hold the same social cachet as it does today. Surgery was more of a trade than a profession, and surgeons often practiced several different trades in addition to setting bones, amputating limbs, and lancing boils. Bradmore’s other line of work was as a metalworker, a term of trade that connotes the ability to execute finer work than a blacksmith would normally turn his hand to. This was fairly common for surgeons of the day, who often maintained a lucrative sideline making and selling surgical tools of their own design.

Bradmore’s first examinations of Prince Henry, which he recorded in a treatise called the Philomena, involved probing the wound to discover its depth and tract. He reports using the pith from the branches of elder wood as a probe, wrapped in linen and soaked in rose honey — a natural antiseptic. With the position of the bodkin determined, Bradmore proceeded to enlarge the wound with a series of larger diameter probes. This was a necessary if agonizing process; entry wounds often close very tightly after the projectile passes, and Bradmore knew he’d need room to work.

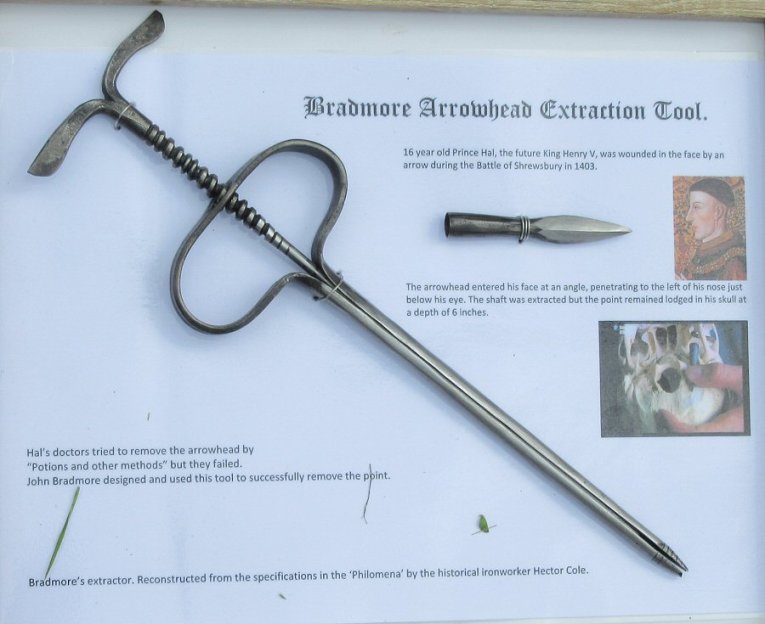

While this slow process of dilatation was going on, Bradmore designed a special set of tongs. In the Philomena, he described it as “[L]ittle tongs, small and hollow, and with the width of an arrow. A screw ran through the middle of the tongs, whose ends were well rounded both on the inside and outside, and even the end of the screw, which was entered into the middle, was well rounded overall in the way of a screw, so that it should grip better and more strongly. This is its form.”

Modern recreations of the tongs require some imagination on the part of the smith, as Bradmore’s description and drawings are somewhat at odds with each other. It could be that the tongs served mainly to guide the central screw into the remains of the shaft; or, if the shaft had pulled out of the bodkin socket cleanly, the tongs could have been forced outward into the walls of the socket by the screw.

Either way, Bradmore was able to grasp the bodkin and, with a little rocking back and forth, removed it from the prince. He filled the wound with white wine, applied a poultice of white bread, flour, barley, honey, and turpentine, and tended to the prince until he healed.

Long Live the King

There’s little doubt that Bradmore saved the future king’s life; a foreign object left in a deep wound would at a minimum lead to septicemia, or, had the arrow driven the anaerobic soil bacterium Clostridium tetani into the wound, a fatal tetanus infection.

For his efforts, Bradmore received a handsome pension for the rest of his life, which was sadly only another nine years. King Henry IV outlived the man who saved his son by a year, leaving the scarred but brave young Prince Henry to ascend the throne in 1413, and eventually go on to win the historic Battle of Agincourt. But none of that would have come to pass had it not been for the luck of a prince and the hacking skills of his surgeon.

Let that be a lesson to all you 16 year olds out there – never lift your visor during battle! But seriously, what a horrible time to have lived. Amazing that someone of this era had the insight to create such a tool. I’m sure it was a bit more “rustic” looking than the re-creation, but obviously it worked.

I’m glad there was some form of anti-septic treatment involved.

I recall reading about a “thieves” potion or something which allowed them to rob houses of those who died/dying of the plague. It involved wiping themselves down with vinegar or something which kept the fleas from biting. Not that anyone knew it was transmitted by fleas…

Yeah, there was a lot of random chance during the plague, a couple of cities avoided it entirely by having all ships wait around 3 weeks before docking, not that anyone knew anything about quarantine

FWIW quarantine procedures (for ridiculous things like menstruation and reasonable things like leprosy) are described in the bible, and the word quarantine comes from the italian words for 40 days, because ships were required to sit outside port for 40 days in the Italian states, after the first black plague epidemics in the mid-1300’s.

There’s evidence that it was the Mongols who brought the plague to Europe by catapulting their dead into fortresses during a siege.

Here’s a great video on it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X-IzdmocMWU

Thieve’s oil still has people touting its curative properties. And some formulations are pleasant, I’ve had a thieves lip balm that was mostly clove with a little mint and lavender that worked well. But it’s the beeswax doing the job there.

From what I’ve seen in old books, thieves oil was garlic oil, tea tree oils, and other stuff to make it tolerable. Tea tree oil is a good antifungal, it can be used in detergent to stop ring worm from spreading. But for humans, it becomes hepatotoxic pretty quickly.

Then there is garlic, and honey. Both very potent antibiotics. There is research showing that both can slow or stop some bacterial growth. Problem is, both garlic oil and honey are breeding grounds for botulinum. Might stop a cut from becoming infected, might kill you.

But because the smell of garlic might give a thief away, they masked that odor. Peppermint, citronella, lavender, and lemon grass were popular fragrances along with clove. Everything in that list, save clove, is good at repelling small insects like fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes.

The folk medicine reasoning, “garlic oil can stop a cut from becoming infected, so it must stop miasma or whatever, too” was miles away from the truth. But pride, and a little precaution, meant no ine wanted to smell like garlic oil and they just happened to enjoy smelling like things that plague vectors hated.

Thanks for the clarification!

I expect it looked as good or better than that recreation – craftsmen of the period really were good, heck craftsmen of many centuries earlier created some really detailed engravings, tools etc. Seemingly took a great deal more pride in the workmanship… Probably because when you don’t have really fancy material processing tools that carve through stock to get your new black for you in half and hour, and new stock delivered next day you really needed to – we bugger up a part and its ‘oh bother I need to order some more blanks’ but they will be there so stupidly fast, back then they probably made a great deal of the ‘stock’ themselves too, and had already spent hours on the raw material processing before doing anything machinist/smithing directly for the final object…

The only thing certain with old crafted objects is that it took them many many more hours than it would take us to get there from whatever point we started, as we have heaps of power tools, fancy cutters much sharper/harder etc..

Back in the early 1990s, my supervisor told me how fax machines, email, overnight deliveries, and such, made us all lazier, and didn’t plan ahead anymore.

The fax machine? But that’s older than the telephone itself! lol

While fax machines have existed for a long time (originally and mostly to transmit pictures for the wire services) there was a sharp change in the technology in the late 1980’s, when they were automated, thermal and xerographic technology supplanted photographic paper that had to be developed, and it was declared that a faxed document could be a legally binding agreement. This vastly expanded the use of the machines until email and other digital methods became ascendant in the new millennium.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of “Just In Time” manufacturing. Bookkeepers hated warehouses full of unsold stuff, as that was expense that wasn’t generating revenue. So they said “hey, let’s only make stuff once it’s ordered so we aren’t paying for stuff we can’t sell at full price.” As long as you knew the lead time between ordering and delivery, it works great. The end result was that manufacturers didn’t even need warehouses; they loaded trucks as fast as they could produce it. I recently saw a documentary on a huge Volkswagen plant where the parts were unloaded from shipping straight to the assembly line.

Faxes, overnight delivery, anything that reduced the lead time was pushed by the Just In Time process.

And it’s a great idea, assuming absolutely none of your suppliers ever has any delays in delivery. Avoiding those problems requires immense planning and careful ongoing management of logistics. It does not engender laziness.

Take a look at some medieval gold jewelry, or even middle kingdom egyptian jewelry.

Their metalsmithing didn’t have the repeatability that ours has, where every part off the machine is identical to the degree we can measure, but their skill in fine details and surface finish rivals what we can do now.

They made all metal mirrors on a regular basis.

I’m impressed at how the surgeon understood the need for antiseptics. While he perhaps did not understand the nature of infections, he understood what helped prevent them. It is interesting how this knowledge didn’t seem to carry forward to later doctors. Indeed, this lack of making use of best known practices seems to occur everywhere in many fields still today. I wonder how it can be best solved?

The healing properties of honey, alcohol, and cauterization have been known about for millennia. However honey & distilled alcohol would have been hard-to-access luxuries for much of history, and cauterization is probably a hard trick to pull off beyond the most superficial of wounds. Sticking a hot poker into someone’s brains probably isn’t the best of ideas…

“Sticking a hot poker into someone’s brains probably isn’t the best of ideas…”

Zombies like their meat cooked. :-D

Cauterisation! Unbelievable what they did in those days.

Of course now as civlilised people we have ELECTRIC diathermy machines. Burning flesh seems to smell the same though.

And I can just remember the late medieval period (1970’s) when I used to use a red hot paper clip to relieve a blood nail (subungual haematoma)

FWIW I’ve drilled quite a number of those for friends, using a brand new #60 drill and alcohol to clean the drill and area.

The sense of relief is amazing, they say.

It’s quite messy when it goes through, though.

At an urgent-care clinic a few years ago, I had a blood nail relieved with the aid of a small electric device that burned a small hole through the nail. The operator said that cauterizing the area around the hole was a benefit.

The pain relief was indeed amazing. It went from excruciating to irrelevant in seconds. The only drawback was that I immediately felt like an idiot for not seeking care the first time it happened.

My mom worked in the office of an ancient iron foundry back in the 1970s. One of her tasks was to drive workers with minor injuries to a nearby clinic. One guy had crushed a thumb creating a painful blood nail, so he decided to use a drill press to pierce the thumbnail to relieve the pressure. The drill bit got caught in the nail and pulled the flesh of his thumb up and into the bit, making the wound even worse.

She says the doctor told him “right idea, wrong tool.”

“Sticking a hot poker into someone’s brains probably isn’t the best of ideas…”

It works with HL2 xbow that has white hot steel bolts as ammo.

I believe Medieval folk were far more intelligent and capable than we give them credit. We have a strangely patronizing attitude to them. It is a bit like saying “Listen dear, sex was invented in 60’s or 80’s or whatever. ” (Hint-it wasn’t).

Very true, at least it seems many people don’t give them the credit they deserve. They probably were in general as individuals less scholarly, with a much narrower understanding than folks in more recent times, though probably more likely to be masters of a craft, where most folks today are rather more generalist in their skill sets. Since the printing press made passing knowledge more freely possible (even those today that very much play the Luddite can’t help but learn about a great deal nobody except the handful of scholar/scientist/gentile’s with interest that seriously studied the nature of things could have known in the past), but as a collective the humans of all eras of history clearly had great skill and understanding, cathedral, castle, viaduct, bridges…

Heck look at devices like the antikythra of no use beyond the scholarly really, and the recorded works that manage to survive from the period and you find they know a huge amount on many things scientific and philosophical before, after and even during ‘The Dark ages’ (much of it is even still ‘correct’ enough that its what we still teach as a foundation, even if we know there are now higher levels of complexity in that area making it ‘wrong’).

Its also clear in any place where native cultures survived long enough to get documented by Europeans just how advanced they were in at least some ways – just being able to live in some areas of the world at all requires great understanding of that environment, which you see when the European explorers turn up and get frostbite, dehydrate etc and often die…

They had less overall knowledge and as a result many people had relatively more broad knowledge than we have now, to the point that it was noteworthy during Ben Franklin’s time that the last few people who knew _everything_, the sum of european knowledge in all fields at the time, were still alive.

I really don’t think you can ever say that, there are too many fields to know, even with the increasing scientistic understanding there is a vast array of bushcraft/natural world understanding that science doesn’t cover very well, even now, and a great deal historical inherited medicines, observations etc that work but nobody knew/knows why and probably nobody outside of that area knew at all.

The more lab and theoretical science type stuff perhaps they did know all, but that is still even now a tiny amount of knowledge compared to how much more has to be out there. Certainly up till relatively recently most who improved science and maths were not specialist in any one thing, but mostly gentleman of significant money so they had the freedom to pursue such endeavours as fancy took them and those people would likely have a very complete picture of the current state of the art. However all the farmers, workers etc who effectively work for them are likely to be basically uneducated in any scholarly way and these workers vastly outnumber the lords and ladies…

People, in general, have probably had the same level of I.Q. for the last 10,000 years, but these people knew nothing, they had to learn everything from the beginning, the reason we are “smarter” than people in the past is because we have built on thousands of years of accumulated knowledge. Raise Einstein in a stone age community and how likely do you think it is he would have come up with the Theory of Relativity?

If we assume that something like Darwinistic evolution, (with some survival/reproductive benefit for being ‘intelligent’) led to humans having a high I.Q., are random mutations in the absence of evolutionary pressure now leading to a decline in natural intelligence? If so, people might have been much smarter in the past.

Better memories at least.

Evolutionary pressures require many thousands if not millions of years to make cognitive changes. However, humanity has likely reached the end of this evolutionary process as we are likely to self-modify in the near future. In the next few thousand years we may become something people of today would envy or possibly scorn but there is no doubt our cognitive abilities will leave them thinking of us the same way we think of troglodytes… and they will be right.

This is the optimistic point of view that I like to see. It’s optimistic to me at least. My decades on earth have been spent witnessing a species destroying our own species in a systematic and random way, in a world that is as a result destroying all species. I have open arms to the enhanced human race, because I believe we can have a solution to all of this pain an misery we bestow on ourselves as a whole, we just have to strive to technologically get there. It’s not a matter of “can we” but really a matter of “will we?”. We shouldn’t ever see war, famine, pain or suffering, if we embrace human upgrades in the coming centuries.

Considering the dropping birth rates worldwide, there is quite strong evolutionary pressure going on now. It is towards some kind of balance between intellectual pursuits (better means to support children) and reproductive pursuits. Genes change slowly, but cultural evolution can be fast.

This is actually a very interesting thought experiment.

Several major discoveries, calculus and special, then general relativity are among them.

Einstein, in particular, could not have formally described his theory as a stone age dude because it requires calculus and advanced mathematics. However, he could have described the underlying philosophical framework. In fact, I would say outside the rarified air of advanced theoretical physics courses, most of us *only* currently have that philosophical understanding, not the rigorous mathematical proof.

Mathematicians / geometers/ philosophers (overlapping to be sure) of antiquity did not have access to advanced math, but had incredible intellect such that they derived many properties of triangles, plane an spherical geometry and arrived at “darn close” numerical solutions to many problems, close enough to be highly practical.

Similarly, in medicine, even the old “humors” model of human physiology is kinda accurate if you think about it. No good language or knowledge at the time to describe blood-borne infection, but the idea that *something* in the blood was causing the problem, fixed by, well, removing some blood (phlebotomy/bloodletting) is actually pretty close.

Surviving preserved skulls show evidence of successful trepanning (removal of a plug of skull) presumably to relieve elevated pressures due to injury or possible tumor. The skulls indicate the patients survived the procedures.

There are many more such examples: Pyramids, Stonehenge, open ocean navigation, even ability to hunt for food and create shelter for survival are all skill that, for the most part, modern humans do not possess.

So I definitely agree that IQ probably hasn’t changed over any meaningful time scale.

Great comment, and had a lot of fun thinking about the implications.

The early vehicle navigation system, ETAK, was inspired by the Polynesian method of finding their way between islands after they were out of sight of any land. They thought of their canoes as being stationary while the world moved, and used the stars as guides to stay on course.

That’s why ETAK and most GPS navigation systems depict the vehicle indicator stationary while the map spins around and moves past it.

Very eloquently put, and very much my thoughts as well.

I suspect we may be pushing the average IQ up a little now, as to function in the modern world requires a great deal more of the sort of intelligence IQ tests tend to study than life pre-industrial revolution I would think – the logic and maths of dealing with a largely computerised world etc, and to be successful in the modern world certainly tends to lean towards the intelligent or sexy, making both more desirable traits…

On the other hand the concepts of social care, medicine, charities like foodbanks,wateraid and the like might actually be causing a shift the other way, making the less capable thrive better than they ‘should’…

I’d also point out that ‘advanced math’ in many ways has existed since the advent of the concept zero and rules governing the basic operands (you could even argue before) – What you need for mathematics is to understand the rules and study the relationships between them, that somebody else has already used those rules to find formula for many useful things just makes somebody who can remember (or lookup) that formula have an easier time looking at something related and beyond (assuming they make that connection)…

So the old thinkers might well have been just as ‘advanced’ in mathematics as we are today, intuitively using the relationships between numbers and the real world even if the idea isn’t codified for easy sharing, its an ever evolving field, with mathematical proof of relationships and formulas we empirically know work in the real world often not existing even now – most things are just statistical approximation, so we don’t have ‘advanced maths’ now either (if you take that to mean a fully developed proof of all the rules you use, and certainty in all answers derived then we definitely do not…). The one thing we do have mathematically now is tools that can crunch vast amounts of numbers for us with great precision in a short time, especially compared to the sliderule/abacus of yesteryear.

“I suspect we may be pushing the average IQ up a little now, as to function in the modern world requires a great deal more of the sort of intelligence IQ tests tend to study than life pre-industrial revolution I would think”

Counterpoint:

Idiocracy

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0387808/

Intriguing concept, never heard of that film before…

Note I made no claims about long term direction of travel, only the current position – while computers are still too dumb to actually function properly on complex tasks unsupervised, and need careful prodding and skilled technicians to function as intended the IQ of the world is likely to tend up, as dealing with computers, especially poorly programmed and cheaply constructed (so full of flaws) computers requires logic, language and mathematical skills that IQ tests tend to focus on.

(I’m also not saying the folks of the past were actually ‘stupider’, just that the world they lived in means the thinking they did was less likely to be of the sort rewarded by IQ tests – I wouldn’t be surprised if they did tend to brawn over brain, when brawn has to be such a big part of daily life – so maybe they were on average stupider, but then the smarts to need less energy and do things efficiently is still a very useful survival trait)

Einstein needed the knowledge that the speed of light was finite, which was proven in the 1700’s. With that knowledge the thought experiment that led to Relativity would have been possible, and Calculus already existed to formalize the equations. Of course Lorentz did this years before Einstein came along, but it was Einstein who made the leap that time and space were themselves changing in order to create the Lorenz contractions which were necessary to explain relativistic phenomena.

I think the Michelson-Morley experiment of 1887 was a very important influence. After all, it gave direct evidence that speed of light was constant regardless of motion.

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.”

The artwork for the article had me thinking this was going to be about saving some old damaged mario game cartridge.

+1

This was just the read that itched my scratch for ancient engineering counterparts to problem solving right now. This was a really good entry, I love the topics that bring light to the innovations that normally only engineers of their time would have been able to appreciate. We can learn so much from past iterative processes!

My great, great, great grandmother Sarah was born in traditional territory along what became the Colimbia river, in 1798. She lived a long time, to 1884, outliving all but one of the children. She died 12 years before my grandfather was born.