Recently Amazon announced that they would be open sourcing the 3D engine and related behind their Amazon Lumberyard game tooling effort. As Lumberyard is based on CryEngine 3.8 (~2015 vintage), this raises the question of whether this new open source engine – creatively named Open 3D Engine (O3DE) – is an open source version of a CryTek engine, and what this brings to those of us who like to tinker with 2D, 3D games and similar.

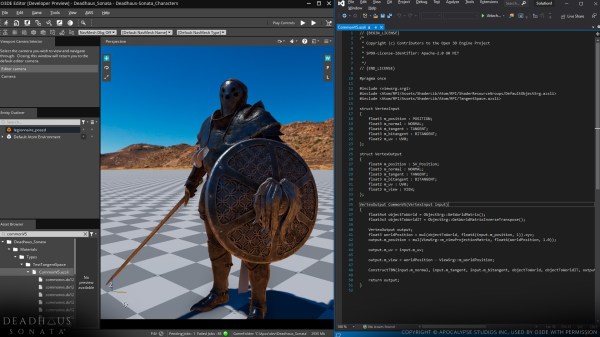

When reading through the marketing materials, one might be forgiven for thinking that O3DE is the best thing since sliced 3D bread, and is Amazon’s benevolent gift to the unwashed masses to free them from the chains imposed on them by proprietary engines like Unity and Unreal Engine. A closer look reveals however that O3DE is Lumberyard, but with many parts of Lumberyard replaced, including the renderer still in the process of being rewritten from the old CryEngine code.

What Makes a Good Game Engine?

My own game development attempts started with the Half Life engine and the Valve Hammer editor, as well as the Doom map editor. This meant that some expectations were set before encountering today’s game engines and their tools. The development experience with the Hammer editor in the late 1990s was pretty much WYSIWYG, and when I was just getting started with Unreal Engine 4 (UE4) a number of years back this was pretty much the same experience, making it relatively easy to hit the ground running. Continue reading “Open 3D Engine: Amazon’s Old Clothes Or A Game Engine To Truly Get Excited About?”