The Space Shuttle’s solid rocket boosters were reusable, although ultimately the overall system didn’t prove cheaper than expendable launches. But given the successes of the Falcon 9 program — booster B1051 completed its 11th mission last month — the idea of a rocket stage returning to the launch site and being reused isn’t such a crazy proposition anymore. It’s not surprising that other space agencies around the world are pursuing this technology.

Last year the India Space Research Organization (ISRO) announced plans for a reusable launcher program based on their GSLV Mark III rocket. The Japan Aerospace Exploratory Agency (JAXA) announced last Fall that it is beginning a reusable rocket project, in cooperation with various industries and universities in Japan. The South Korean space agency, Korea Aerospace Research Institute (KARI), was surprised in November when lawmakers announced a reusable rocket program that wasn’t requested in their 2022 budget. Not in Asia, but in December France’s ArianeGroup announced a reusable rocket program called Maïa.

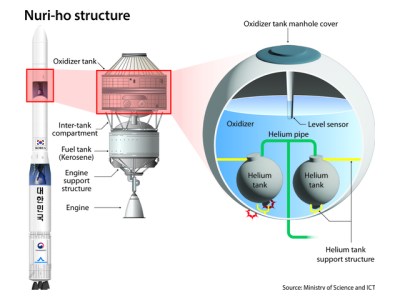

Speaking of South Korea’s rocketry program, we wrote about the Nuri rocket in October which failed to reach orbit because of a problem in the third stage. Kari recently completed a review of all the data, and concluded the problem was with the anchors of the helium tanks which are located inside the oxidizer tank.

Apparently the changing buoyancy of the submerged tanks with altitude wasn’t completely accounted for in the design of the mounting brackets. When they ultimately failed, the resulting broken piping caused a LOX leak and the subsequent 46-second premature engine shutdown. The next scheduled launch in May 2022 will very likely be delayed.

> booster B1051 completed its 11th mission last month

So what’s the bottom line? Did it actually save the cost of the recovery system and break even as foretold by Musk, or do we need to wait for more data from a whole fleet of them to say it didn’t?

one of space x’s ambitions is to increase the number of launches/week they can sustain,reusable rockets is one way to do that and practicing with starlink is how to get good at it.

the goal is orders of magnitude greater than what is happening now.

It looks like they’ve been good enough for a while. They are already the cheapest launch provider, so there’s zero incentive to lower the prices (especially not since they have to fund expensive development programs), and at current prices, the market isn’t growing “orders of magnitude”. Probably even at lower prices, market growth is limited by cost of making/running a satellite.

Yes. It worked. The goal was 10 flights per booster, and the passed that and expect 20 flights from their current fleet. Even ULA’s spreadsheet predicts cost effectiveness at this level of reuse. As mentioned, SpaceX’s flight rate *and* flight costs are industry leaders. I can’t imagine why anyone would claim in the comments that the reusable booster program has not been successful — you just have to look at all the other folks starting reusable booster programs to see that this conclusion has been independently reached numerous times.

It’s kind of amazing what you can do with the trifecta of the last decade’s glut of capital, the greed of the vulture capitalists, and the relative flexibility of the regulatory framework when you have that much cash at hand.

SpaceX has brought in $7.1B in investment, and about half again more in fees. In round numbers, the total cash spent so far is about $100M per launch. At a customer price of $65M per launch is that break even? That’s actually really hard to tell — there are so many ways to interpret the numbers.

The later investors in the pyramid, like the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan ($300M), are paying back the original investors, who are being being rewarded handsomely for their early vision and boldness.

The bottom line? With the financial skulduggery involved, the victors will write the history as they see fit.

Any proof for that or are you just talking?

The numbers and the fact that the early investors are recouping their investment at many multiples of their cost is a matter of public record. As is the fact that schoolteachers in Ontario are in for about a thousand dollars each.

Early investors making a substantial profit after the company retired existential program risk and established a revenue stream isn’t unheard of, nor is investing in an organization with a strong track record and substantial potential for market growth. My issue is with your claim SpaceX is flying at a loss.

I made no such “claim SpaceX is flying at a loss.”

It’s clear SpaceX has not yet grossed enough revenue to pay back their investment, but it’s a safe assumption they have priced the launch service to cover their marginal costs and thus exhibit (at least to investors) they are not flying at a loss.

After all, you don’t get to $100B valuation on a $7.1B investment by showing you are losing money.

But: Though it’s not a terribly fair comparison, a mature company (for example, General Electric) 2020 valuation (market capitalization) was about the same $100B, largely based on its revenue that year of $80B.

Clearly the people writing the SpaceX company prospectus, and the investors believing it, feel there will be much greater future income to support that $100B valuation, not the paltry $1B they might gross this year.

So, does SpaceX have a reasonable expectation of $80B of annual revenue to support that $100B valuation? I have no idea, but for reference, that’s a Falcon 9 launch every 7 hours, every day, all year long.

“glut” in Polish means “snot”

Space X and Elon have claimed a cost benefit from reusing the Falcon 9 first stage. One just had to dig a bit for data. But here is a quote from Elon recently from the site Inverse.com.

Payload reduction due to reusability of booster & fairing is <40% for F9 & recovery & refurb is <10%, so you’re roughly even with 2 flights, definitely ahead with 3."

The Falcon 9 rocket is working pretty well, but the lower cost of operation has not resulted in lower cost for the end user, nor has it led to a growing space market. The rocket mostly flies for its own Starlink program, and service missions to the ISS.

It’s suffering from space-shuttle-itis as predicted. The quickest time to refurbish a booster for another flight has been 27 days against Musk’s 24 hours target for the turnaround time. There’s all sorts of little “issues” that crop up and delay the process, such as having to clean up the soot deposits off the fuel pump turbine after every use. Naturally, the faster you try to do it, the more money it costs.

https://www.elonx.net/spacex-statistics/

“Space-shuttle-itis” is an absurd phrase to use in this context: the Space Shuttle flew a total of 135 times over a 30 year period between 1981 and 2011. The site you linked yourself shows 143 Falcon launches in its 14 year lifespan — more total launches in half the time, with 31 of those launches in 2021 alone — ie almost 7 times higher than Shuttle’s 4.5/year average rate. Given that the Falcon launch rate has steadily increased year-over-year, it’s reasonable to suppose Falcon will achieve at least an order of magnitude improvement.

And unlike Shuttle, there is a large (and growing) fleet of Falcon boosters, allowing the turnaround between launches to be as short as 15 hours, even though the quickest turnaround for any particular booster is currently 27 days. With 31 launches in 2021, the *average* turnaround time between launches is under 12 days if you don’t artificially limit yourself to considering only launches of one particular booster.

As you mentioned, there’s no particular reason to spend money to speed up turnaround of a single booster faster, when you can just parallelize booster processing. The overall flight rate is ultimately what matters.

Not true. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Falcon_9_and_Falcon_Heavy_launches

ISS resuply flights in count are really dwarfed by other non-Starlink launches.

And they have one of the cheapest launch services on the planet for a long time 60M$ per Falcon 9 which is 15.6t to LEO (reused).

It absolutely has resulted in lower cost for their customers (I’m not sure who you count as the “end user”) and a growing space market. A F9 launch is now stated to cost $62M for a solo mission on a recovery profile (5400kg to LEO), or $1M for 200kg in a rideshare to LEO[1]. These are hugely influential pricepoints as it’s now affordable to get something into space (200kg is a lot!). The head of Roscosmos cut pricing by 30% in 2020, explicitly citing pricing pressure from SpaceX[2]. About half of their recent launches are starlink, with even some of those having commercial rideshares. As a breakdown of 2020 and 2021[2]:

2020:

-13 Starlink, 3 of which included commercial rideshares

-6 NASA launches (1 science launch, 1 suborbital unmanned, 1 orbital non-station manned, 3to the station)

-3 military launches

-4 dedicated commercial (Korea, Argentina, Turkey, SiriusXM)

2021:

-17 starlink, 2 of which included commercial rideshares.

-7 NASA launches (5 to the station, two science launches)

-1 military launch

-5 dedicated satellite commercial (including two very prolific rideshare launches)

-1 crewed commercial

If one tallies the launches excluding those for ISS programs or Starlink (I’m still not sure why we aren’t counting ISS missions in the counts, but I’ll play by your rules), that’s 8+3partial for 2020 and 8+2partial in 2021. Those numbers are only exceeded by Russia and China[5][6]. It’s far more than the perennial US launch provider, ULA, provided either year.

There are myriad analyses of exactly how heavily the F9 has affected the launch market[3][4]. While the market for raw launch numbers overall hasn’t really gone up (if one disregards Starlink, which is kind of fair to do), it’s only stayed where it is because SpaceX and Rocket Lab are there to pick up the slack from ULA, though I imagine Russia or maybe Arianespace could have picked up the slack for way more $$$. I also think rideshares that send ~100 satellites should be given a little more weight than one large commercial satellite launch, but that’s definitely up for debate.

Dismissing the F9’s launch market significance because most of its launches are for Starlink is just hiding numbers behind statistical abuse.

https://spacenews.com/op-ed-spacexs-adaptation-to-market-changes/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Falcon_9_and_Falcon_Heavy_launches

https://arstechnica.com/science/2021/03/european-leaders-say-an-immediate-response-needed-to-the-rise-of-spacex/

http://interactive.satellitetoday.com/via/august-2021/liftoff-launch-forecast-for-the-year-ahead/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_in_spaceflight#By_country

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2021_in_spaceflight#By_country

Whoops used GTO numbers for reuse profile. Should read 15,000kg to LEO, not 5400kg.

> A F9 launch is now stated to cost $62M for a solo mission

Sure, that’s not a bad price, but it’s been holding steady since the beginning. The big discounts that were promised with reusability never materialized. I didn’t mean that the NASA launches should not be counted, but they should be counted separately, since they don’t represent the market demand for cheap access to space.

I’m not sure if that price holding steady should be used against SpaceX. After all, it’s a price no-one else can compete with, why not rake in that free margin?

I think the rideshare missions represent the beginnings of market demand for cheap access pretty aptly. There have been three dedicated rideshare missions, and a bunch smaller-count rideshares hitching along with mostly Starlink missions. I’m really not sure how hundreds of extra spots in space, even if they’re between 1kg and 200kg, is an absolutely enormous new market.

Looking at the planned launches for this year, there are tons of ridesharing missions, from 5-count up to the ~100-count. They’re also planning on more than doubling the number of commercial and government launches from the last couple of years. Now, that’s in the future, but the F9 has done a pretty good job of meeting targets the past few years.

I just don’t see how, even if you disregard NASA, defense and Starlink launches that they aren’t opening up the market. Their numbers are so large in absolute terms that their commercial grown only looks small when looked at as a percent of their own business, which is no way to gauge effect on a market.

There is no reason to lower the price when you’re already the lowest cost launch provider by kg into orbit. That is the real problem for SX’s competition. Especially if Starship is successful. The real problem for SX is going to be having enough paying payloads to put into orbit or space.

There will be a gap or a lack of missions. If SX could land 100’s of tons on the Moon or Mars, that hardware is no where ready to be launched yet. Tourism might be the answer but space travel is still very dangerous and expensive. The economics of reuse is a function of how many times you can the rocket. A 2 year flight to Mars means it can only be used 5 times in a decade. A weekly flight that performs 25 orbits in LEO means 52 times a year and 520 times over a decade. Divide the capital cost by 5 or 520 times you’ll end up with a much different cost per flight with say a $500 million rocket.

That launch tower in the Title Photo looks so cool in its symmetry.

(Almost like a winged Asian god)

Funny. I’m twitchy because it’s *not* perfectly symmetric. It hurts to look at it, and makes me annoyed at the photographer.

I’m suffering from terminological confusion. When we discuss the “COST” of a “LAUNCH”, do we mean:

A. The total, end-to-end launch price to a customer? (i.e., “We’ll get your to for .”)

B. The total, end-to-end cost to the operator of a launch or average operator cost per launch derived from launches? (i.e., “Don’t mention this to the customer, but it’s going to cost us get their to , and we’ve got to add our profit margin atop that.”)

C. The total, end-to-end launch price to a customer, including recovering, refurbishing, and returning to full function the reusable rockets? ? (i.e., “We’ll get your to for , plus a rocket refurbishment fee.”)

D. The total, end-to-end cost to the operator of a launch or average operator cost per launch derived from launches, including recovering, refurbishing, and returning to full function the reusable rockets? (i.e., “Don’t mention this to the customer, but it’s going to cost us get their to , plus reusable rocket refurbishment, and we’ve got to add our profit margin atop that.”)

E. Any of the above cost/price variants, subtracting market/investment income?

F. Something else?

The conversation seems to be comparing apples, oranges, and ducks as identical entities.

It’s “F.” in spades.

With the financial manipulation tools available to modern high finance money handlers, they could justify any number they choose to quote. Any number you hear is what they chose you to hear, whether it’s to attract more investment, invite more business, intimidate a competitor, reduce (i.e., eliminate) tax burden, or any other of a myriad of reasons. The SEC does bring a bit of control and transparency to the process, but at the multi-gigabuck level of finance they’re just outgunned.

You’re free to choose any of the other definitions of ‘launch cost’ too — just state your assumptions when called to defend it.

I’m suffering from terminological confus hen we discuss the “COST” of a “LAUNCH”, do we mean:

A. The total, end-to-end launch price to a customer? (i.e., “We’ll get your [full_payload_object] to [target_altitude] for [price].”)

B. The total, end-to-end cost to the operator of a launch or average operator cost per launch derived from [n] launches? (i.e., “Don’t mention this to the customer, but it’s going to cost us [n] get their [full_payload_object] to [target_altitude], and we’ve got to add our profit margin atop that.”)

C. The total, end-to-end launch price to a customer, including recovering, refurbishing, and returning to full function the reusable rockets? ? (i.e., “We’ll get your [full_payload_object] to [target_altitude] for [price], plus a rocket refurbishment fee.”)

D. The total, end-to-end cost to the operator of a launch or average operator cost per launch derived from [n] launches, including recovering, refurbishing, and returning to full function the reusable rockets? (i.e., “Don’t mention this to the customer, but it’s going to cost us [n] get their [full_payload_object] to [target_altitude], plus reusable rocket refurbishment, and we’ve got to add our profit margin atop that.”)

E. Any of the above cost/price variants, subtracting market/investment income?

F. Something else?

The conversation seems to be comparing apples, oranges, and ducks as identical entities.

what’s helium needed for and why it’s tanks are in oxygen tank?

It replaces the oxygen as it is pumped out

The COPV strut failure is somewhat embarrassing, as after CRS-7 that failure mode should have been well-known and caught in advance at the design stage.

Also hilarious to see the SpaceX-can-do-no-right brigade out in full force as usual. After the failure of:

– Well, they’ll never actually land a booster!

– Well, they landed one, but they’ve never re-use it!

– Well, they re-used it, but they’ll never be able to re-use it more than once!

– Well, they re-used it more than once, but they’ll never get NASA or the DoD to fly on a re-used booster!

– Well, NASA and the DoD flew on a re-used booster, but their target was 10 flights, right? Call me back when they do that, or the whole idea is junk!

I guess the goalposts have moved so far down the field and out of the stadium that all that’s left is to complain about standard accounting practices.