We don’t always acknowledge it, but most people have an innate need for music. Think of all the technology that brings us music. For decades, most of the consumer radio spectrum carried music. We went from records, to tape in various forms, to CDs, to pure digital. There are entire satellites that carry — mostly — music. Piracy aside, people are willing to pay for music, too. While it isn’t very common to see “jukeboxes” these days, there was a time when they were staples at any bar or restaurant or even laundrymat you happened to be in. For the cost of a dime, you can hear the music and share it with everyone around you.

Even before we could record music, there was something like a jukebox. Coin-operated machines, as you’ll recall, are actually very old. Prior to the 1890s, you might find coin-op player pianos or music boxes. These machines actually played the music they were set up to play using a paper roll with holes in it or metal disks or cylinders.

Early Days

That changed in 1890 when a pair of inventors connected a coin acceptor to an Edison phonograph. Patrons of San Francisco’s Palais Royale Saloon could put a hard-earned nickel in the slot and sound came out of four different tubes. Keep in mind there were no electronic amplifiers as we know them in 1890. Reportedly, the box earned $1,000 in six months.

Imitators soon followed, sometimes in the form of companies that made player pianos or other instruments like Wurlitzer. Typically, the coin mechanism would unlock the crank you had to turn to wind up the old-style phonograph. The song you heard was the record on the player. That changed in 1918 when an inventor figured out how to stop and restart a record automatically. By 1927, the American Musical Instrument company had a jukebox that allowed you to pick among two sides of ten records, for a total of twenty selections. Keep in mind, that these machines weren’t called jukeboxes yet, but you’d clearly recognize them as one today.

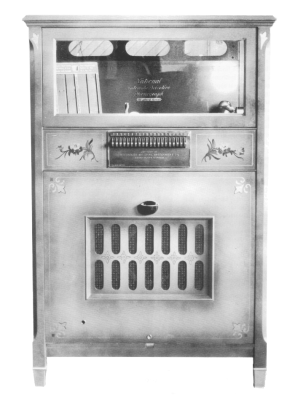

Around the same time, Seeburg — a player piano maker — built a coin-op box with an electrostatic speaker and could pick from one of eight complete turntables. The very first models played the records in sequence, but the 1928 Autophone could select from the eight songs available.

Automation

Most of us can probably imagine how we would build a controller to play a few records on demand. You could stack the records and use multiple needles. You could put the records in a holder that rotates. There are probably a dozen other ways you can think of. But consider this: during most of the jukebox’s life, there were no microcontrollers. Everything had to run with switches, solenoids, timing motors, cams, and things like that. Want a look inside a typical jukebox? Watch the video below.

Golden Years

By the 1940s, jukeboxes begin looking less like furniture and more like the showpieces you think of today. That’s about the time the name was coined, as well. It would be the 1950s, though, before the classic 45 RPM singles would replace other media in the boxes.

Jukeboxes started to get fancy right before World War II, with lights and moving features. During the war, though, unnecessary production was banned, so machines went back to basics for a while. After the war, though, the machines got more and more grand to attract attention.

One thing that became very popular was a wallbox. This was essentially a remote control for the jukebox that allowed, for example, restaurant patrons to pay for and select music from their seats.

When radio became prominent, it seemed to doom the record industry, but it didn’t. The jukebox was a key consumer of records and some estimate that in the 1940s, three-quarters of all records produced in the United States wound up in a coin-op box. By the 1960s, though, the jukebox became less popular, even though around this time the started playing in stereo — a novelty, at the time.

They are still around though, just not as prevalent. A modern jukebox is most likely found in a bar and either uses CDs or digital music, possibly downloaded over the Internet.

The Mob Connection

One popular brand of jukebox that started in the 30s was the Rock-ola. Named after rock music in the 1930s? Actually, no. The company was founded by reputed mobster David Rockola and also made scales, furniture, and rifles for the military. Despite the 1922 blues ballad, “My Man Rocks Me (With One Steady Roll),” the term “rock and roll” didn’t enter music parlance until the 1950s and, in fact, was actually a euphemism for something completely different before then.

Rock-ola wasn’t the only jukebox company associated with organized crime. AMI — formerly the American Musical Instrument company — was reputed to be run by mobsters for a time. In 1949, Chicago mob boss Mooney Giancana took over a jukebox distributor who operated a network of machines. From there, the mob systematically took over other distributors including Century Music company who operated 100,000 machines in 1954, out of a total of around 575,000 machines in the country. The whole affair was subject to a congressional investigation in 1958 where it was revealed that some jukebox operators were even murdered to take over their routes.

Sounds of Silence

Jukeboxes were once so popular, that if you were having a drink or a meal, there was bound to be music. In fact, research showed that if the jukebox was playing, it was more likely to be fed more coins to keep playing. To that end, distributors used to paint nickles a certain color — usually red — and leave them with the owner. When the operator took the money out of the jukebox, the colored coins were not part of the profit sharing.

In addition, sometimes you didn’t want to hear the jukebox. For the cost of a song you could play a blank record called “Three Minutes of Silence.” For some machines, it was the most played record at times.

On Your Own

We’ve known people who enjoyed restoring old jukeboxes. However, their relative scarcity makes it expensive to acquire any good ones, unless you happen to get lucky. If you get a real junker, you could trash the insides and do something more modern. There’s no reason, of course, that you can’t build your own from scratch.

[Banner image: “Jukebox – 1947 Wurlitzer model 1080” by Paulo Philippidis. Thumbnail image: “jukebox” by Liz West.]

PLEASE don’t gut a classic Wurlitzer to put a Raspberry Pi in it.

I would love to see more people actually integrate the Pi into the original system, but not take away the original functionality. Maybe have it set up so when you select a certain record the Pi can kick in and play something of your own.

Not sure how ‘uncommon’ it is, but acquired a Wurlitzer 3600 superstar around 15 years ago. I’ve never considered it to be a particularly attractive or desirable machine, it’s more on the plain/utilitarian side. I wouldn’t mind replacing the guts with a computer, and replacing the amplifier with a cleaner, more efficient unit.

If this were a model where the mechanical functions were visible for the world to see during operation, I might feel a bit differently,

That is a horrible idea, why would you want to ruin the experience of the jukebox? The coin going down the slide, the ectro mechanical sounds of the mechanism coming to life and the very distinctive sound of a 45rpm planig.

I’ve got 10 of those wurlitzer s and unless someone takes them they all just be in a landfill cause i thought someone would want one and honestly I can’t give one away let alone the 50asking price

Are they 50s style jukeboxes? And where are you located? jerrybakerll55@gmail.com

My name is Erma G and I have a 70’s Seeburg Jukebox with disco ball and is trying to find a buyer. My email address is ermagayles@att.net. If someone is truly interested in purchasing it. Email me. Thanks

I would like to know what models u have and r u up to selling any as I live in Baltimore md I really love Juke boxs

I just restored an Edison phonograph amplifier horn to functionality for a local museum. Those were really good at entirely passive sound amplification. Quiet speech into it is blaringly loud. It’s hard to not just march about yelling into one.

Rare, uncommon? There is a totality of “touch tunes” wall boxes in almost every public place in town. One outfit since the 50’s runs all of them. They dispense low grade digital noise with one note low bass and a screeching narrow-band treble. Just the opposite of 3 minutes of silence option they allow another patron for a price to override a legitimate play to be pushed back down the cue. That’s theft of service. Signs on the console at family restaurants may have a warning the establishment will void the play if it drops the bomb. The owner used to have total control over what was in the jukebox, now all the filth & garbage gets aired weather the rest like it or not. “Music” gets played not for our enjoyment but to irritate the rest of us by one…

We have a Seeburg stereo model made only a year or two after stereo came out (’57) even though I never saw a stereo 45 till the late 60’s. I remember seeing one in ’59, Channel 1 and channel 2 emblazoned on the 2 grilles of the lower part of the console. It used magnetic core memory for the play-cue. They apparently had easy listening double song 33RPM discs that let us hear Montevani cascading strings in stereo as well as rock and roll 45’s.

It’s not “theft of service” because you state very clearly that you did not ever expect to hear anything but noise. And I Really want to be there to see you press it further.

You sound like great fun at parties

In 1980, someone I knew got a contract to computerized a record pressing p!ant.

No Raspberry Pis, but Intersil 6100s. Certainly because they were CMOS but maybe because it ran PDP/8 code. A controller for each press, it was about timing, just an upgrade to the existing record press.

He did hire someone who did know the PDP/8 to program it.

Some Seeburg jukeboxe that could hold 100+ records, such as the V200 from 1955, used magnetic core memory to keep track of what selections were queued. This was one of the first commercial uses of core memory tech.

I equiped one of my broken old radios with an internal bluetooth reciever so I can stream good music from a nice looking furniture via bluetooth.

Since it doesn’t have a remotecontrol for on/off, i connected it to a wifi wallplug for that slow startup and glow, although the blutooth manages everything else

I’m in the process of restoring a 1939 Wurlitzer model 600A. It plays 78 RMP records, of which it can hold 24. I’m amazed at how much was able to be done mechanically that we would rely on computers to do now. This makes it a real pleasure to work on and learn from.

I inherited a 1962 seeburg full of 45s from my dad. I don’t want to gut it, but currently the arm doesn’t work properly and the thing is just so freaking heavy that I am thinking about just taking it all out

I don’t have the jukebox. Dad had to sell it years ago. But I have two Rubbermaid tote boxes full of Seeburg 45’s. I haven’t played them yet, but I think some are iconic artists and some are like instrumentals for a fore runner of Karaoke?

Wow, this article is so very wrong! Jukeboxes have made an amazing comeback, these electro mechanical wonders are the a great mix of Art and engineering, the distict glow of a machine that lures you in for that nickle in your pocket and in some cases gives you a show for your money. This article generalized an amazing part of our history, with thousands of collectors world wide the jukebox is alive and well.