For a large part of the 20th century, motion pictures were distributed on nitrate film. Although cheaper for the studios, this film was highly flammable and prone to decay. On top of that, most film prints were simply discarded once they had been through their run at the cinema, so a lot of film history has been lost.

Sometimes, the rolls of projected film would be kept by the projectionist and eventually found by a collector. If the film was too badly damaged to project again, it might still get tossed. Pushing against this tide of decay and destruction are small groups of experts who scan and restore these films for the digital age.

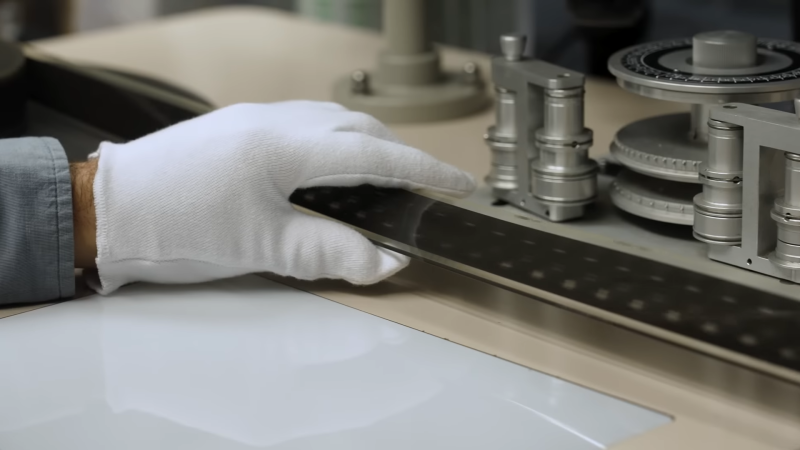

The process is quite involved – starting with checking every single frame of film by hand and repairing any damaged perforations or splices that could come apart in the scanner. Each frame is then automatically scanned at up to 10K resolution to future-proof the process before being painstakingly digitally cleaned.

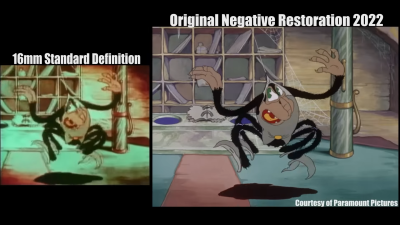

The real expertise is in knowing what is damage or dirt, and what is the character of the original film. Especially in stop-motion movies, the subtle changes between frames are really part of the original, so the automatic clean-up tools need to be selectively reined in so as not to lose the charm and art of the film-makers.

The results are quite astonishing and we all have teams like this to thank for protecting our cultural heritage.

If you’re interested in watching the process, then check out the video after the break. If you fancy a go at automatic film digitising yourself (preferably not on unique historical prints!) then we’ve shown projects to do just that in the past.

Thanks to [Cliff Claven] for the tip.

I worked on the digital part of this process for Pixar and Kodak Cinesite, and our work was used to restore “Snow White” and other classical films. The point about nitrate film base is not simply that it was horribly flammable (like its relative nitroglycerine), but that it was organic, and mold liked to eat it. So, although the classical negatives were kept in climate-controlled vaults for 50 years, they still rotted right in the film cans.

The first part of the restoration process was chemical cleaning. Next is what I think is the most impressive part: the “wet-gate” telecine. Wet-gate means that the film was immersed in a fluid with the same refractive index as the film base, so that all scratches were filled and became invisible. The gate is the part that holds the film frame still while it is being digitized (or in the context of a projector, being projected). The film was digitized while it was immersed in the fluid at the gate, thus the “wet” gate. Film photography and special effects of the pre-digital age had a lot of genius mechanical and optical engineering like this that is still interesting to study.

Following digitization, the film was processed by algorithms, and also hand-painted on an electronic paint system to fix the worst blobs. The resolution used was one you might achieve at home today, but was the most sophisticated equipment of the time. Because there are 24 frames per second and over an hour of film, the operator was expected to spend 1-2 minutes per frame, and no more.

I wrote an image processing language called Iceman for this, which unfortunately only got used on this project and a few others. The very restricted use of my work at Pixar was one reason I moved my work to Open Source – my work at Pixar generally had less than a dozen actual users, while pretty much everything I have written for the Open Source community continues to be used 30 years after its creation, and has a huge community.

Great info, thanks for sharing. And for open-sourcing your work!

One of my projects involves AI research, and as POC I’m writing a program to process digitized old 78 records to remove the noise, clicks, and pops, and another to process digitized old video and remove the dirt speckle, scratches, and frame misalignment.

There’s a lot of redundant information in video and audio, and a human listener/viewer would have no problem identifying the dirt blobs on a frame, or the scratch wandering across several frames: to the human, it looks as if the video happens behind the scratch, and your visual system simply fills in the missing frame info.

If the human has no problem identifying the image behind the noise it should be possible for a program to do that as well, but this is a tremendously difficult problem. It’s much more than just comparing sequential frames.

I have a copy of “Popeye meets Sinbad” (1936) digitized by the National Archives from original film to play with (available on project Gutenberg). I hope to have a process that does a lot of the remastering automatically, with a list of changes so that a human operator can choose which mods to use.

It is an undeniably good thing that we’re saving this history.

And I don’t want to be a Cassandra here, but one sad issue is that once these restorations are out of the hands of the dedicated individuals who do this work, the data for all these projects is probably going sit on a shelf in an LTO cartridge for 75 years before someone realizes that *those* archival copies have gotten pretty flakey now. And the circle of film life continues.

I’m going to think that nobody is going to fund making sep negatives and putting them away in a mine for some unknown viewer a century from now, but the film world could really use some sort of archival preservation program that copies this data to fresh media every couple of decades. It need not be enormously expensive because media is fairly cheap and assuming you do it before problems start it could be highly automated. But good luck funding it.

One of the most challenging restauration up to date in the motiion picture’s history was the one of George Méliès “Le voyage dans la lune” (A Trip to the moon) in colorized version, thanks to the involvment and patience of Eric Lange, founder with Serge Bloomberg, of Lobster film company in France.

A fascinating documentary relating the work of Méliès and the history of this restauration is “Le voyage extraordinaire”, released in 2011. A copy of this documentary is available here: https://archive.org/details/LeVoyageExtraordinaireSergeBrombergEricLange2011._201904 (french soundtrack + hard spanish subtitles. May be an english version is available somewhere else…).

The part regarding the restauration start at 42′ with the find of unique copy in Spain in 2001. But this copy was considered by all companies/specialists in the world as too decomposed and stuck to ever be possibly restaured. So, in despair, Eric Lange started to experiment in his basement by exposing the concrete bloc like reel to chemicals, in order to painstakingly soften and release the outer part of the reel, detach a few frames at a time and photograph them with a digital camera in a short lapse of time before the film becomes hard and highly breakable again. It tooks him a whole year to accumulate around 10.000 individual digital frames! But this was only the beginning of the process… The final restaured version was released in 2011, ten years later!

I’m also a collector of film reels (some hundred of reels, in various formats: 8, 9.5, 16, 28, 35mm, some probably already more than a century old) and like many others, i have a huge problem: film scanners cost A LOT. Good ones can cost, at the very least, 10/20k€, and up to several hundred k€! This is very unfortunate, and debatable since technology involved in them (basically precision mechanics, led/laser lighting and up to 44Mpixels image sensor + computer storage/processing) is no longer as challenging and costly that it was in the previous decades. Compared to the cost reduction in other areas, such scanners should cost probably an order of magnitude less, and should be wildly available to allow preservation of these decaying films ASAP…

Since there are plenty of home ‘cam scanning’ rigs available – designed to position, align, and illuminate a 35mm (or medium format or large format or etc) frame with a DSLR or mirrorless camera with a macro lens mounted, with several (e.g. Valoi) able to be at least semi-automated with frame advance and shutter triggering – the main problem is reliable film transport that can handle delicate/distorted/damaged film.

Then you have the software to allow restoration in a timely manner, rather than spending several minutes per frame manually removing imperfections. If that’s only available when bundled with an ‘expensive’ film scanner it’s a moot point: the software is the expense, and you may as well use the hardware with a support team than the hardware you’ve cobbled together.

If they have a real restoration of cobweb hotel I would love to see it.

I like when peoples that do not understand the matter try to teach other, give advices and fill articles in this, otherwise respected web site. Please, strictly conform to ESP32 and mechanical magic and do not more publish articles about professional film/video restoration. Here, comments are much more interesting and useful than main article. This is unacceptable for this, otherwise interesting and useful, site that I read with a pleasure.

I’m delighted to see so many knowledgeable people in the comments offering their experiences and insights. One of the great strengths of Hackaday is the community, who have expertise in so many unexpected areas.