A thermoelectric generator (TEG) can turn a temperature difference into electricity, and while temperature differentials abound in our environment, it’s been difficult to harness them into practical and stable sources of power. But researchers in China have succeeded in creating a TEG that can passively and continuously generate power, even across shifting environmental conditions. It’s not a lot of power, but that it’s continuous is significant, and it could be enough for remote sensors or similar devices.

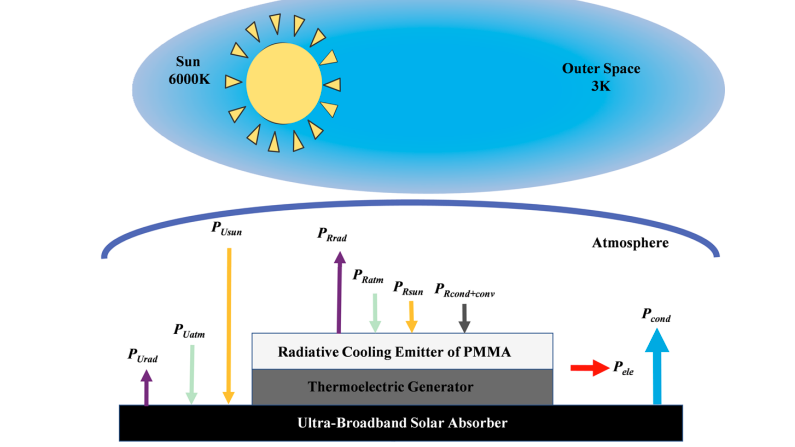

Historically, passive TEGs have used ambient air as the “hot” side and some form of high-emissivity heat sink — usually involving exotic materials and processes — as the “cold” side. These devices work, but fail to reliably produce uninterrupted voltage because shifting environmental conditions have too great of an effect on how well the radiative cooling emitter (RCE) can function.

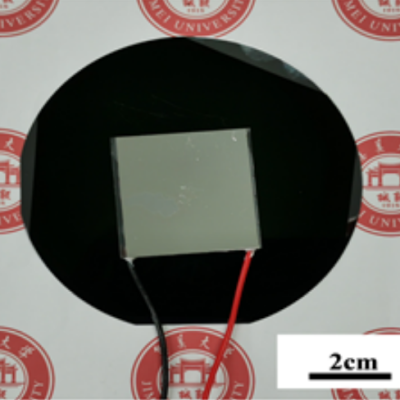

Here is what has changed: since a TEG works on temperature difference between the hot and cold sides, researchers improved performance by attaching an ultra-broadband solar absorber (UBSA) to the hot side, and an RCE to the cold side. The UBSA is very good at absorbing radiation (like sunlight) and turning it into heat, and the RCE is very good at radiating heat away. Together, this ensures enough of temperature difference for the TEG to function in bright sunlight, cloudy sunlight, clear nighttime, and everything in between.

As mentioned, it’s not a lot of power (we’re talking millivolts) but the ability to passively and constantly produce across shifting environmental conditions is something new. And as a bonus, the researchers even found a novel way to create both UBSA and RCE using non-exotic materials and processes. The research paper with additional details is available here.

The ability to deliver uninterrupted power — even in tiny amounts — is a compelling goal. A few years ago we encountered a (much larger) device from a team at MIT that also aimed to turn environmental temperature fluctuations into a trickle of constant power. Their “Thermal Resonator” worked by storing heat in phase-change materials that would slowly move heat across a TEG, effectively generating continuously by stretching temperature changes out over time.

> As mentioned, it’s not a lot of power (we’re talking millivolts)

:/

No, we are clearly talking apples. Just as related to power without further details.

For some actual information, see the paper:

https://opg.optica.org/oe/fulltext.cfm?uri=oe-31-9-14495&id=529179

Oops. Forgot to paste the link.

it’s not the voltage alone which makes the power!

Made me cringe too. Who reviews these articles?

Luckily the paper provides answers: Power ranges from 3.85 mW/m2 to 879.25 mW/m2 depending on the temperature difference.

is that like full square meters?

3.85 milliwatts as opposed to 250-400 Watts per square meter in sunlight for a solar panel. That is like 5-6 orders of magnitude less power.

The research seems purely academical. I think in almost any application you could just throw solar at it.

It is not that much impractical. Provided a large surface is used to scavenge ie. Solar heat or it os attached to a stove, chimney or a metallic object exposed to heat/fire, and the low side sinks heat ie. In water, it could be a watt or two. See here: https://youtu.be/Rd_fl2QUI7U

You’d be very lucky to get a whole Watt out of a single TEG using this kind of system. Most data sheets massively over rate their TEG performances. Lower your expectations by at least 3 orders of magnitude!

And when you do your calculation you will find it is cheaper to buy a battery than

can power your device for >10years.

I want to see a TEG built to connect to an internal combustion engine exhaust pipe. It would need multiple TEG elements, connected to make 13 to 14 volts. With that setup the alternator could be smaller so there’s less load on the engine. Making electricity from waste exhaust heat would be “free”, no additional load on the engine.

Honestly this is one of the best applications for them. Exhaust heat TEGs could probably replace alternators entirely, other than in those new cars that turn off the engine every time you stop so they can game the emissions regulations.

How long will it take to generate as much energy as put into the making ?

My guess would be about 100 years, but could be 1,000.

More like 10000 years with the cited numbers

I’ve always wanted to load up a bunch on the underside of solar panels with water cooling to complete the sandwich

why is the power measured in milivolts ?!

I don’t think it could ever be better than solar panel+battery ? Maybe it could be a great low-tech option.

Yep.

The only area I could see it being better is where a battery won’t work (extreme heat, extreme cold) or where it needs to work for longer than a battery could last.