Unless you work for the government or a large corporation, constrained designs are a fact of life. No matter what you’re building, there’s likely going to be a limit to the time, money, space, or materials you can work with. That’s good news, though, because constrained projects tend to be interesting projects, like this airborne polarimetric synthetic aperture radar.

If none of those terms make much sense to you, don’t worry too much. As [Henrik Forstén] explains, synthetic aperture radar is just a way to make a small radar antenna appear to be much larger, increasing its angular resolution. This is accomplished by moving the antenna across a relatively static target and doing some math to correlate the returned signal with the antenna position. We saw this with his earlier bicycle-mounted SAR.

For this project, [Henrik] shrunk the SAR set down small enough for a low-cost drone to carry. The build log is long and richly detailed and could serve as a design guide for practical radar construction. Component selection was critical, since [Henrik] wanted to use low-cost, easily available parts wherever possible. Still, there are some pretty fancy parts here, with a Zynq 7020 FPGA and a boatload of memory on the digital side of the custom PCB, and a host of specialized parts on the RF side.

For this project, [Henrik] shrunk the SAR set down small enough for a low-cost drone to carry. The build log is long and richly detailed and could serve as a design guide for practical radar construction. Component selection was critical, since [Henrik] wanted to use low-cost, easily available parts wherever possible. Still, there are some pretty fancy parts here, with a Zynq 7020 FPGA and a boatload of memory on the digital side of the custom PCB, and a host of specialized parts on the RF side.

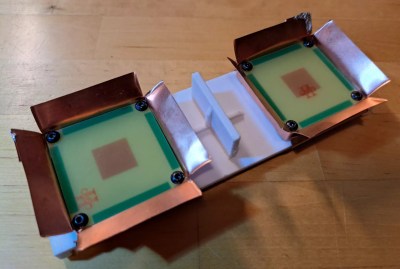

The antennas are pretty cool, too; they’re stacked patch antennas made from standard FR4 PCBs, with barn-door feed horns fashioned from copper sheeting and slots positioned 90 to each other to provide switched horizontal and vertical polarization on both the receive and transmit sides. There are also a ton of details about how the radar set is integrated into the flight controller of the drone, as well as an interesting discussion on the autofocusing algorithm used to make up for the less-than-perfect positional accuracy of the system.

The resulting images are remarkably detailed, and almost appear to be visible light images thanks to the obvious shadows cast by large objects like trees and buildings. We’re especially taken by mapping all combinations of transmit and receive polarizations into a single RGB image; the result is ethereal.

This is insane. Making a camera with low freq RF instead of light

Do it at microwave frequencies and you can see even more. I ran experiments with bistatic radar using Canada’s Radarsat as the illuminator, at 5.6 GHz. You can see if corn fields have been harvested or not.

They thought I was weird because I didn’t want the image from space. Naah, just wanted illumination.

Wow. I want one.

Very impressive !

2nd

Amazing work, write-up and results!

In underwater imaging there is something similar using Synthetic Aperture Sonar, with very expensive equipment. I wonder how good his findings and implementations could be transfered to that field to get budget / DIY solutions for that :D

A major expense of low cost SAS is a transducer and driver that can produce a high power chirp. There are plenty of cheap ones that are single frequency resonant piezo material. But the chirps, or a broad band noise source, are essential for resolution.

I have tried a few ideas over the years but none worked out. If there is one, curious people want to know.

Ceramic piezos are narrowband because of the ridiculous impedance mismatch between the ceramic and water: You need an impedance transformer to couple to the water. It’s that quarter-wave transformer impedance matching layer that imposes the bandwidth limits. Also, a ceramic that isn’t effectively coupled to and damped by its acoustic load will have a high ‘Q’ and ring like a mofo, so will act like a sensitive but narrowband transducer.

Using a low acoustic impedance piezoelectric polymer, like PVDF, gets you a much better impedance match, much wider bandwidth, at the cost of less efficiency and power handling afforded by the polymer.

One approach is to transmit with a high power ceramic, with a broadband (but not very efficient) impedance matching layer, and listen with an intrinsically broadband PVDF receiver. In space-constrained applications you can even transmit through the PVDF layer, but it gets quite a whack on transmit and you need to wait many microseconds for the ringdown before you can hear echoes.

I actually have some PVDF from when it first became available. I got q collection of samples from someone. I still have the literature somewhere. I got films and thick walled tubes about 12mm in diameter and 3mm long. At the time, the high voltage drive needed was not so easy.

Magnetostrictive was the hot item for high power and way beyond price and power I was looking for. All my other ideas had coupling issues. I thought about plastic lenses and mirrors or sparkers. As long as you record the outgoing signal you can correlate with the returns and noise should be unique. Hammer pounding things with a solenoid wear out. Anyway, I moved on but still have some of the stuff. I think about it from time to time because the correlation for the detection and the Fourier Transform are so “simple” and fast today even on a Blue Pill.

Impressive performance!

I wonder if it could be used at lower altitude to search for mines in a field.

Yes, if you use the correct frequency. Ground penetrating radar is classic.

if they’re on the surface (not buried) – prob. yes, at least the anti-tank ones. Small ones might be problematic due to the relatively low frequency (7.5-5cm wavelength). Might be solvable with more GPU number crunching though…

No, if you’re thinking of penetrating very far into the ground. The deeper you go, the lower the frequency you have to use, and the worse your resolution thereby.

Maybe, if they’re near the surface and the ground is dry enough. Yes, if it’s clear ice and you can image through a km of it like it was glass.

Yes, if they’re near the surface and your antenna is dragged across the surface so there’s good coupling into the soil, thereby boosting your S/N to something near achievable. I recommend you get a robot to do that.

Yes, if you are just looking for disturbances that could be a mine. You’ll have to go out and check them out.

I spent five years or so looking for mines, but not that kind. We imaged a zinc mine that went down 150 feet into rock, got nice pictures.

Dang cool project! (Next, drone mounted LIDAR)

That’s what PulsedLight (Bend, OR) did, and that’s why Garmin bought them. Now sold as the Garmin LIDAR-Lite. The cheap ones are only good to 10m. The better ones to 40m. The sky is the limit, so to speak, from there.

HAD missed an important part of the story:

“After ordering the PCB I made an order for the components from Mouser. The order seemed to succeed fine and they accepted my money but I got the above email afterwards telling me that they can’t sell me one of the components. Reason seems to be that the supplier of the component has forbidden them for selling it to individuals. This was very frustrating as there was absolutely no warnings on the website and I had already ordered the PCBs…”

Probably on the ITAR list. You coulda been a Commie. I had no problem but I had friends at the Pentagon.