Everyone has a standard for publishing projects, and they can get pretty controversial. We see a lot of people complain about hacks embedded in YouTube videos, social media threads, Discord servers, Facebook posts, IRC channels, different degrees of open-sourcing, licenses, searchability, and monetization. I personally have my own share of frustrations with a number of these factors.

It’s common to believe that hacking as a culture doesn’t thrive until a certain set of conditions is met, and everyone has their own set of conditions in mind. My own dealbreaker, as you might’ve seen, is open-sourcing of code and hardware alike – I think that’s a sufficiently large barrier for hacking being repeatable, and repeatability is a big part of how hacking culture spreads.

This kind of belief is often self-limiting. Many people believe that their code or PCB source file is not a good contribution to hacking culture unless it meets a certain cleanliness or completeness standard. This is understandable, and I do that, too.

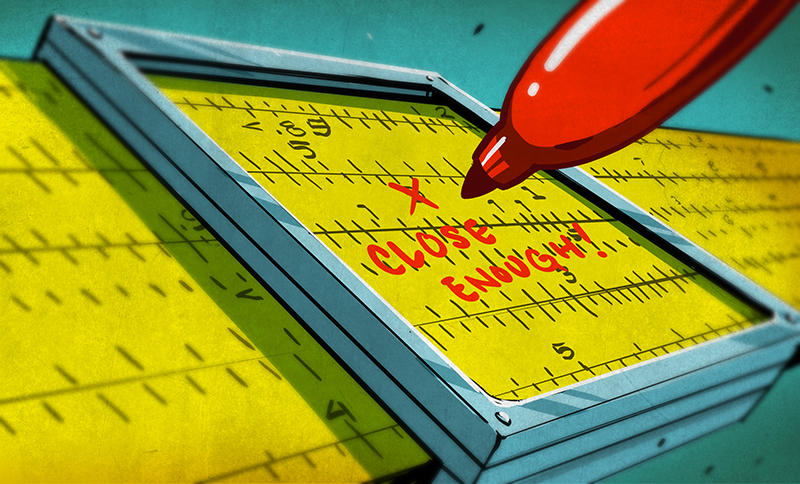

Today, I’d like to argue against my own view, and show how imperfect publishing helps build hacking culture despite its imperfections. Let’s talk about open-source in context of 3D printing.

The Snazzy Ugly Duckling

One little-spoken aspect of 3D printing is how few models are open-source. Printable models published exclusively as STLs are commonplace, STEPs are much less popular, and from my experience, it’s soul-crushingly rare to see a source file attached to a model on Printables. I struggle to say that’s a good thing, and quite obviously, that negatively impacts 3D printing culture – getting into 3D modeling is that much harder if you can’t reference the sources for 95% of models you might get inspired by.

Of course, part of that is that 3D CADs are overwhelmingly closed-source paid software, and there are like five different ones with roughly equal shares of usage. It’s hard to meaningfully share sources from within a paywalled siloized market. Also, unlike software source code, STLs are very much cross-platform. Electronics has a way better analogy for STLs, they’re just like gerbers – gerbers are easy to export, and to inexperienced people, they’ll feel like all that anyone would ever need.

Then, there’s a self-consciousness and perfectionism. While rare, I’ve seen “I will clean this up and publish later” happen in 3D printing spaces too – it’s a thoroughly non-viable promise there too, but I get why people say that, I’ve personally made and failed on such promises a good few times myself. I’m glad that this isn’t a popular excuse so far, but, as more people adopt OpenSCAD, Blender, and FreeCAD, with their universally-accessible files, maybe we’ll see it resurface.

Asking for 3D model sources should probably become part of hacker culture, just like it helped with software. I don’t think it’s great that 3D printing so often implies closed-source 3D models, and undoubtedly that has limited the growth of 3D modeling as a hobby. I strongly wish I could git clone the 3D model projects I find online, and there’s a whole lot of models that are useless to me because I can’t git clone and modify them.

At the same time? 3D printing carries the hacker flag quite strongly, despite the imperfections, and you can notice it by just how often 3D printing appears on our pages. We can and should point at aspects of hacker culture that 3D printing doesn’t yet represent, and while at it, we benefit from the technology, as much as its imperfections hurt us.

Where Is Hackerdom Found?

Would I argue the same about Discord servers? Mastodon-hosted threads? YouTube videos? GitHub repos with barely-documented code? For sure. There’s no shortage of criticism about those, mostly about accessibility issues. Servers and videos are often not externally discoverable, which is surprisingly painful for hacker culture’s ability to thrive and grow. At the very least, we are badly missing out – for instance, I’d say Discord servers and YouTube videos alike are in dire need of external log/transcript hosting capabilities, and tech-oriented Discord servers specifically could benefit from public logs in the same way that modern Discourse forums have them from the get-go.

That’s for the disadvantages. As for upsides, YouTube videos make hardware hacking into entertainment for potential hackers not enthralled by scrolling through a blog interspersed with pictures, and, they position hacking culture in front of people who’d otherwise miss out on it. Let’s take [DIY Perks], a hugely popular YouTube channel. Would that dual-screen laptop build we covered have worked out great as a blog post, or maybe as a dual post-video, as some hackers do? For sure. At the same time, it gets hacking in front of people’s faces.

Discord blows as a platform, and I’ve written a fair bit about just how much it blows. One such snippet is in the article I wrote about the Beepy project, where the Discord server was crucial to growing Beepy as a community-contributed project. Would people benefit from the Beepy project having publicly available logs? Most certainly, and I’d argue it’s hurt the Beepy project being more externally discoverable. Is that all?

Discord has been an unprecedented communications platform for the Beepy project, and we’d outright lose out if there weren’t hardware hacking communities thriving on Discord, like Hackaday Discord does. I think we should remedy these kinds of problems by building helper tools and arguing for better cultural norms, just like we did with software licenses, because giving up on platforms like Discord currently has a significantly subpar cost-benefit analysis.

What about imperfect code? Sometimes, a hacker figures out a small part of a sensor’s protocol or a basic feature, and as much as the code might be insufficient or hastily written, they publish it. Have you ever stumbled upon such a repository? I have, sometimes I was happy, and sometimes I was disappointed, but either which way, such code tend to require extra work. In the end, I’ve noticed that it almost always helped way more than it hurt, which in turn has eventually led to me publishing more and more.

I think we’d benefit from a culture where “publish later after cleanup” is replaced by “here’s the code, and I might push some cleanup commits later”. It’s a better contribution to hacker culture and to people who enjoy your work, and the “might” part makes it more honest. It’ll also get your publishing muscles in better shape so that you’re quick to post about things you really ought to post about. For what it’s worth, I don’t think it hurts if this is assisted by social media likes, too.

Strength Through Presence

Survival of hacker culture has so far heavily relied on its presence in media all across, and an ability to press the “maybe I can hack too” button in other people’s brains through that presence. That said, every non-open 3D model, Discord server with non-public logs, YouTube channel with non-transcribed videos, or a completely ephemeral TikTok channel, still palpably paves a way for future hackers to join our communities, wherever hackerdom might be within ten years’ time.

I think the key to informational impedance mismatches is making it easier for people to meet the high standards we expect, and helping people meet them where appropriate, in large part, by example. It looks like hacking is strongest when present everywhere, even when some seams, and I hope that this kind of overwhelming presence helps us overcome modern-day unique cultural hurdles in a way we couldn’t hope for just a decade ago.

if you have an STL, you have least a fighting chance of reverse-engineering that part (Hacker boss level 1 complete!!), drop it into your favourite cad app, convert it to a solid and have at it!! Start with measurements, remove triangles that split up large faces, project those faces into sketches and you can build off of that, your slicer may also be a good source for grabbing measurements without needing to dump the STL into a cad app but learning the simple cad stuff can get you a long, long way.

It’s easy to write that but not so easy to reverse stuff but that’s where you start, just like you do when you’ve dumped the emmc from a ‘locked’ device so you can get at that one single binary that doesn’t play nicely with the new kernel that you’re thinking you might want to install, baby steps gets you closer to your target.

I think all of the available sources of information are as good and bad as they’ve ever been, it used to be IRC before discord and you had to know about IRC to start using it, well known in hacker circles, not so much for your average person wanting to get started…

Discord is on all the app stores, accessible via a browser and a myriad of hardware devices, has video, audio and image handling functions built right in, way better than IRC without even trying. Youtube is a as good and bad as it’s ever been, I never appreciated having to wade through 30mins of video for the 10seconds of gold that I actually needed but that’s just the way it is and has always been.

I think the biggest thing is that the ‘elders’ fill in the gaps with sage advice wherever possible, work with the tools you’ve got, or make new tools or refer back to ‘lost’ tech to make the things you need.

It’s odd, discord is indeed like IRC enhanced, but the enhancement makes it.. not IRC.

And I’m not too overwhelmed by it.

I prefer to design my own parts instead of redesigning something others created. It takes me much less time to understand the part design and recreating it in my preferred CAD program, than importing an STL file, converting it to a solid and cleaning it up. I tried that twice, to modify someone else’s designs for better resilience. In one case I just gave up. In the other I dropped the model into Blender, added a cylinder, made an union and cleaned up extra faces. Took me a solid hour. After that I stopped trying to edit STL files.

On related note I document every project that might end up published soemday. Especially source code after returning to one of early projects and not knowing, what was my intention with in writing the certain parts of source code. If someone tells you that source code is its own documentation, ask them to figure out how Duke Nukem 3D engine works without looking it up in documentation…

I once converted a toy model STL of Hellboy’s Arm of Doom into something that actually could be worn over someone’s actual arm and, as much as I felt good that I was able to do it, it felt like hell for a good couple of hours making sure all of the modifications would actually be printable. I don’t mind modding but I avoiding it like the plague is the usual go-to with all the extra work to do something even as simple as putting a grip bar in the right orientation and thickness to take some force.

with that said, I fully agree with spinning up your own version of an object even if it turns into a bad and shoddy clone. As long as it works well enough… /shrugs

IRC is a protocol. DIscord is a product. IRC have logs, msot of the time they’re public so work and progress can be archived and used many years later. Discord conversations are not archived for the public to see. Wnen Discord will shutdown (they will), then we’ll lose a good chunk of knowledge on a myriad of matters.

Protip: if you use Discord for your projects, be sure to archive on another platform all your logs

Gives me seriously something to think about because I still have 3-4 projects that I want to publish but where I keep telling myself that I need to cleanup the code first or take some nice pictures or whatever my excuse is.

Some of my code is even already in GitHub so would be easy to share but I want to share the full package with people.

When it comes to design data and 3D files, I pretty much exclusively work with Onshape now and also share my public documents where people can either just get the step files out to print and recreate a project or the can even get the entire document history with full feature trees to the parts to change, adapt or improve the designs. I have made use of that myself in the past and it has helped me even just finding a design of a SBC like Raspberry Pi or a Pico or some boards from Pimorini to design and enclosure around.

Well in any case, I need to get my butt up as publish more!

Again, a part design’s source is the annotated mechanical drawing, which nobody bothers to draw. It’s not the original CAD design files you have: those too lack most of the crucial details and don’t explain much.

The source for the 3D model is in your head, and your intent is documented as “source” by drawing the part out and marking what materials and tolerances etc. you intended it to have. With the part drawings, you have provided that information to anyone in a software-independent manner so other people can re-create it using whatever software they want to use.

In terms of programming, you can think of the CAD model files, or the stl/step files kinda like bytecode or even the compiled binaries, stripped of all the comments and notes. You can reverse that to the original programming language notation with some difficulty, but you’ll have to re-invent the wheel to understand it.

Information like “This is an M5 clearance hole with such and such tolerance class” isn’t transmitted. You can measure the nominal dimensions from the model, but you don’t know the intent so you can’t adjust it to your process without asking the question. After all, it might be a 10-32 instead, and the actual hole diameter was arbitrarily chosen to result in a close or loose fit with the original designer’s 3D printer. If you copy it as-is then you’ll have different results.

When manufacturing parts, you can’t rely on exact models because every process to make the part will have its own character. You have to communicate the intent and demands of precision and accuracy, so the person actually making the part can change how they work to result in the part you want.

If you use OpenSCAD you can add context and narration to the part in the source. A simple comment saying “M5 clearance hole, centred 10mm from edge to avoid binding” can be in the code. Self documenting code FTW!

It’s possible that OpenSCAD could be modified to implement a “meta” tag for every element in the source, so that you could hover the mouse over some feature in the rendered view and see the tag describing its purpose or some other notes (which you can currently sort-of do, but it links back to the line of source code that produced that element). Maybe Fusion, for example, allows you to tag an element or operation with some metadata.

You can, but is it standard the way everyone can use?

More to the point: mechanical drawings have standardized the annotation of features like that so there’s no two different ways to say “clearance hole”, or even the need to specify it in such ambiguous terms. You give it an acceptable tolerance and mark it down in a way that stands out. If no special rule applies, then general tolerance classes are assumed (specified elsewhere).

There are conventions to say things like “this surface should be parallel to that surface by such and so degree” and that should be perfectly unambiguous and explicit, rather than hovering your mouse over every detail of the part to see whether special rules apply.

But hackers are not trained to do this. So they don’t.

Specified where? In ISO norms costing thousands of Euro?

XDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDD

No hacker will buy those because that costs as much as used car or a very, very good gaming rig (think quad RTX 5000 in SLI, easily can get 300 FPS in any game).

@ford ASME Y14.5, for the most part. The 94 edition can be bought for the price of a new novel and is still happily accepted by any machine shop that actually reads the drawings. Not too much has changed since then, unless you really care about defining inspectable precision shafts.

That said, I don’t particularly agree with Dude’s hard-line stance. That works for defining requirements on suppliers for a project of some scale, but most places a hobbyist will get a cheap part from (protolabs, pcbeay, etc.) will not look at the drawing, even if you pay them the nominal upcharge to do so. For that (and also for making drawing-defined parts more manufacturable), it’s much better to try and get a handle on best practices:

– Imagine how the part is set up (setup counts, machine axis requirements)

– Imagine how the cutter travels through the part (interior corners aren’t perfectly sharp, fillets can sometimes make things much harder to cut, don’t ask a 1/8″ end mill to make a 3″ deep channel)

– Try to expect tolerances no tighter than +/-0.005″. Many shops can do 0.03″ daily-in and day-out, but this is dependent on them having good quality processes and the part being manufacturable.

By you. In the same document, if so desired. If not, the shop will use whatever standard tolerances they default to, which they should tell you.

That may be the case, and you pay for the cheapness in parts that may not come out to tolerances if you happen to need them. That still doesn’t absolve you of the need to define such tolerances in case you want to remember what they were, tell someone else what they’re supposed to be, or if you want to complain that they weren’t followed, and then send the part to a fab that actually does read the drawings.

The way I’ve been trained, the part isn’t defined until you have draw the diagram that explains to the person making it exactly how to make it.

Hiding information in code comments does not count. You give them the diagram and say “make this”, and that diagram should contain all the relevant information. Other information elsewhere, such as optional actions to take if the part could be made in a different manner, is either irrelevant or possibly ambiguous or conflicting, so it should be ignored by the maker. You don’t want to confuse the person doing the job, because it results in delays. If there are some other documents that further specify the demands, they are referred to in the top level diagram so the person knows to look for it rather than hunt for it. I can’t fault them for not looking if I haven’t said “look here, this is the information you need”.

Sometimes the fabricators will catch on details you forgot to include, and ask for clarification, and other times they will just blindly follow what you’ve told them and the end result may or may not fit. The part may turn out okay and then the next time it won’t, because the person doing the job changes and they get a different idea of what you meant. In the latter case you can only blame yourself.

Information is not ”hidden” in code comments. The point is that they are visible and accessible in OpenSCAD. I don’t know if it’s possible to do something similar in other CAD software.

FreeCAD has a technical drawing module, where you can do your drawing and use that to produce the 3D model. I think one thing you might be overlooking is that a 3D model is the result of reading the drawing, and, as you lament, the original information from the drawing is lost, unless it’s annotated somewhere. This is particularly an issue when there is no drawing, just an idea immediately parlayed into a 3D model. It’s even more important to capture the key thoughts that led to a specific design feature.

In the case of OpenSCAD the code replaces the drawing. There needs to be a way of incorporating the well-defined standards of engineering drawing into the code.

I flick between creating DXF files for parts and importing them into OpenSCAD and extruding them to make 3D objects, and just transposing the dimensions from a drawing to create an object from nothing. Both ways produce results. The first is more work, but provides more complete documentation. The second is more practical.

tl;dr I agree with you, but I’m not sure where the problem lies, nor what the solution is.

Apropos to Andrew’s reply (I can’t directly reply under his comment) but I agree that OpenSCAD needs a way to incorporate CAD measurements and constraints into the code.

For a number of my OpenSCAD projects I draw up a ‘symbol drawing’ in CAD where variables in the code are used in a 2-view or 3-view diagram attached to the project. This way someone can get a visual idea of what something is without having to run and muck with it. Sort of analogous to the symbol table generated when assembling assembler code, which is where I got the idea from.

For example here is the symbol diagram that goes with the OpenSCAD code (named at the top) for my IBM Selectric typeball on Thingiverse: https://cdn.thingiverse.com/assets/85/71/40/6f/47/large_display_Selectric_II_typeball_symbol_key.png

Here we have to note that there’s in fact two different “drawings”. The typical workflow in most software starts from a constrained sketch, which many people confuse to be the drawing, and follows with a 3D model, which is then brought to the drafting workbench and projected in different views to produce the actual part drawing. That last step isn’t necessary if you’re modeling for personal use, so it is usually not done, yet the definition and documentation of the part is not complete until you have.

Maybe.

Maybe the difference between a drilled hole and drilled then reamed hole is in the specification and everybody understands that.

Like code comments, don’t comment the obvious.

Machinists don’t generally want ‘how’ from a GD engineer, they want a tolerance that they can do and no impossible parts.

If the machinist is asking the engineer how the F they’re supposed to make something, the engineer already Fed up.

And that often means they don’t want to read up tables of tolerance classes to figure out what your specification means, they just want you to write down the +/- value directly in the drawing. Sometimes it’s good to specify what interference class you aim for, in case anyone has any questions, but often that’s just superfluous information from a manufacturing standpoint.

The easier they can get at the information, the faster and cheaper you get the part made with fewer errors and misunderstandings. That is the point of the annotated technical drawing.

AI chatbots can make OpenSCAD stuff I hear, and that means you can also feed it a script and have it add the comments.

You can have it make up comments, which may or may not be related to the design.

You would think Andrew but it’s quite amazing how AI bots can analyze code and tell you what it does, and do so correctly.

It’s odd how they pour trillions in AI but what the stuff it is good and useful for is very niche.

It can tell you what it does, but it can’t double guess your intent.

I use github for a backup. after hours of tinkering, it would be terrible to have a hardware problem and lose all my work. I really would like to collaborate on some of my projects too. even just constructive criticism can be valuable. I always put “work in progress” or something if there are serious bugs.

In the old days there were no Discord, GitHub, social media, Youtube, and even forums or IRC. There were Usenet and BBSes. And earlier not even that. A true hacker had to figure out everything on their own, especially the kind that liked to get into someone else’s system. There was documentation, sometimes incomplete or incorrect. Some people dumpster dived, broke and entered restricted areas and did illegal or questionable stuff just to gain some knowledge. And hackers not always were willing to share their knowledge with other hackers.

In 2000 I found an obscure local zine on phreaking. In one file it explained how old token operated public phones kept the token locked below the magnetic sensor until next token was dropped in and registered by optic barrier. So when first 3 minutes (1 token) was near its end one could bump the phone from the bottom with a knee, the token would pass by magnetic sensor, break the barrier and then fall back and get registered and dropped into the lockbox, giving extra 3 minutes for free. This file was public because almost all token phones were gone and replaced with phone card models. There was such a phone in my school that was also a boarding school. It was in the boarding section next to main stairwell and offices. I told this trick to my classmate and he tested it. It worked splendidly. Except one small detail. Turns out that bumping the bottom of a big metal box full of brass tokens hard enough to propel one of them in the mechanism makes quite a lot of noise. And it also teaches one how to keep a straight face when asked by angry vice-principal what was that horrible noise…

And that’s real hacking, not whining about the lack of proper documentation or editable source files…

For “hacking” i’m inclined to agree with what i take to be the thesis, that the 1% of the work that produces the prototype is valuable to share even without the 99% of the work that might produce something genuinely useful. I love the diversity of garbage out there — hacks that don’t work, hacks that work but aren’t documented, and every color in between. I genuinely enjoy that you can download software written by hardware guys and schematics designed by programmers. Just about everyone has a different hammer in their hand that they use to squash every problem, and the mismatches are fun, when hacking.

It becomes a very different thing when we’re talking about open source as a tool for software engineering. There’s definitely a certain amount of ‘worse is better’ that i subscribe to. But it’s a little upsetting that in 1999 i decided not to switch to ALSA (Linux sound interface) because the only API documentation was for a prototype that had already been abandoned by the time ALSA was integrated into mainstream kernels, and now i have switched to ALSA more than 20 years ago and it is still undocumented. There are a few abortive disparate attempts to document different aspects of it, but i don’t have to go out of my way to find corners of the API that are still completely undocumented. But it’s usable because it really is decently-well-designed, because it did stop moving shortly after becoming main-lined (iow, defacto standardization by inertia), and because there’s now a huge reservoir of example code to learn from.

But then you get to things like systemd where everything is an undocumented one-off hack of the lowest quality, intermittently debugged by a few distro guys who silo themselves off from everything. And defended by a rabid group of fanboys who read the tutorial and actually fell for the lies in it. They’re doing the simplest tasks and finding that they work (or alternatively, that they were able to throw up their hands and give up without consequence) and declaring that the idiom of units actually is a basic building block and not merely a distraction from a million nested special cases hardcoded in the C source. Just unbelievable amounts of fury inspired by this charley foxtrot. Of course, my anger evaporated when i found out i don’t really have to use it. That determines a lot about the experience of a bad hack: are you trapped inside of it?

There’s definitely a spectrum of quality in contributions, and a spectrum of consequences.

Aka. the “works for me, what are you even complaining about?” comment you get over Linux not being usable for the vast majority of people.

That art work is going to give me nightmares! Writing on your slide-rule with a marker? NOOOOOOOooooooo!

As someone who at separate points in time have released open source projects and also attempted to patent and manufacture technology. The cutoff is always what is minimally viable.

The open source projects was just how to brew coffee in a saucepan without sipping a ton of coffee grounds. Something with a very strange story attached to it.

The attempt at patenting a project was having a really good idea that can functionally reduce the surface drag of any vehicle by a confirmed 3 percent but theoretically upwards of 90 percent. It was such a good idea that a team of engineers at Airbus in Europe had the same idea 16 years prior.

In both situations the cutoff was when I had the bare minimum that I could bring to the next step.

Quoting Steve Boies: “Make it work, make it good, make it great.” (Implicitly: In that order.)

Yeah, that’s pretty much it. Like recently, I’ve been designing a pet feeder, sort of similar to the one in the link. https://www.kingshengpcba.com/pcb-assembly/pcb-and-pcba/wireless-communication-systems-pcb-assembly.html. I’ve been learning from their approach, but I’ve definitely run into a lot of the obstacles you mentioned. The good thing is, things are getting sorted out bit by bit. I agree with what that guy in the replies said: ‘Make it work first, then make it great.

One thing with publishing your work is why are you doing it – if your home hobby project is done quickly and more for fun but might also make up part of your resume professionally then publishing the more rough scratch pad workings out version…

The working project demo looks good, seeing the bailing twine, gaffa’s tape, hope and prayers holding the whole mess together enough to get that first demo project on the other hand. I know I’d be a lot less inclined to hire somebody that published a messy darn nearly unreadable codebase that even they won’t be able to work on in a few months once the idea goes out of their head. But I also know that is exactly the sort of work I’d do for myself in many cases as I don’t care, the point of the exercise to me was to test or learn something further down the line and all the stuff underneath isn’t very important as long as it works well enough to get to that later stage.

As she says, we all get to define ‘hacking’…

But ‘It’s not hacking unless it’s open source’ is just idiotic.

How do others feel about Non-Comm licenenses in otherwise Open Source projects.

I hate it. I mean… for more artsie stuff like 3d printable figurine models I think it’s fine. But for open source machines I don’t think so.

A non-comm license is just open enough that you can still get a large community built up around a well designed project. But that just means it is less likely that a more open version will come around. (Yes I have a project in mind but don’t want to name names). I like the way 3d printers turned out where there are still Open Source designs but you can chose which parts you want to DIY and which you would prefer to just order pre-made.

Don’t get me wrong. You designed it, you own the design. If you only are willing to release under a non-comm that’s your right and not ours to violate. But I’ll pick the project with a more open license when I am choosing what to build next. And if you aren’t yourself trying to make a business around the project then what is the point of disallowing commercial use? If I am releasing something I would rather the viral nature of a GPL-like license where if a company wants to include my stuff with theirs’s they have to open up their own too!

non-comm license guarantees that I won’t modify or remix a file. It’s not worth my time and hassle if I can’t truly use it. If anything I’ll remake the model from scratch.

I came back to this because I’m currently in a pickle with non-comm. I need a printer part in metal, metal printing is expensive, and the processing/shipping/tariffs adds up to more than the part. My “$30” part will cost almost $90. If the model allowed commercial use, I’d order 10 and sell the rest.