After you have written the code for some awesome application, you of course want other people to be able to use it. Although simply directing them to the source code on GitHub or similar is an option, not every project lends itself to the traditional configure && make && make install, with often dependencies being the sticking point.

Asking the user to install dependencies and set up any filesystem links is an option, but having an installer of some type tackle all this is of course significantly easier. Typically this would contain the precompiled binaries, along with any other required files which the installer can then copy to their final location before tackling any remaining tasks, like updating configuration files, tweaking a registry, setting up filesystem links and so on.

As simple as this sounds, it comes with a lot of gotchas, with Linux distributions in particular being a tough nut. Whereas on MacOS, Windows, Haiku and many other OSes you can provide a single installer file for the respective platform, for Linux things get interesting.

Windows As Easy Mode

For all the flak directed at Windows, it is hard to deny that it is a stupidly easy platform to target with a binary installer, with equally flexible options available on the side of the end-user. Although Microsoft has nailed down some options over the years, such as enforcing the user’s home folder for application data, it’s still among the easiest to install an application on.

While working on the NymphCast project, I found myself looking at a pleasant installer to wrap the binaries into, initially opting to use the NSIS (Nullsoft Scriptable Install System) installer as I had seen it around a lot. While this works decently enough, you do notice that it’s a bit crusty and especially the more advanced features can be rather cumbersome.

This is where a friend who was helping out with the project suggested using the more modern Inno Setup instead, which is rather like the well-known InstallShield utility, except OSS and thus significantly more accessible. Thus the pipeline on Windows became the following:

- Install dependencies using vcpkg.

- Compile project using NMake and the MSVC toolchain.

- Run the Inno Setup script to build the

.exebased installer.

Installing applications on Windows is helped massively both by having a lot of freedom where to install the application, including on a partition or disk of choice, and by having the start menu structure be just a series of folders with shortcuts in them.

The Qt-based NymphCast Player application’s .iss file covers essentially such a basic installation process, while the one for NymphCast Server also adds the option to download a pack of wallpaper images, and asks for the type of server configuration to use.

Uninstalling such an application basically reverses the process, with the uninstaller installed alongside the application and registered in the Windows registry together with the application’s details.

MacOS As Proprietary Mode

Things get a bit weird with MacOS, with many application installers coming inside a DMG image or PKG file. The former is just a disk image that can be used for distributing applications, and the user is generally provided with a way to drag the application into the Applications folder. The PKG file is more of a typical installer as on Windows.

Of course, the problem with anything MacOS is that Apple really doesn’t want you to do anything with MacOS if you’re not running MacOS already. This can be worked around, but just getting to the point of compiling for MacOS without running XCode on MacOS on real Apple hardware is a bit of a fool’s errand. Not to mention Apple’s insistence on signing these packages, if you don’t want the end-user to have to jump through hoops.

Although I have built both iOS and OS X/MacOS applications in the past – mostly for commercial projects – I decided to not bother with compiling or testing my projects like NymphCast for Apple platforms without easy access to an Apple system. Of course, something like Homebrew can be a viable alternative to the One True Apple Way™ if you merely want to get OSS o MacOS. I did add basic support for Homebrew in NymphCast, but without a MacOS system to test it on, who knows whether it works.

Anything But Linux

The world of desktop systems is larger than just Windows, MacOS and Linux, of course. Even mobile OSes like iOS and Android can be considered to be ‘desktop OSes’ with the way that they’re being used these days, also since many smartphones and tablets can be hooked up to to a larger display, keyboard and mouse.

How to bootstrap Android development, and how to develop native Android applications has been covered before, including putting APK files together. These are the typical Android installation files, akin to other package manager packages. Of course, if you wish to publish to something like the Google Play Store, you’ll be forced into using app bundles, as well as various ways to signing the resulting package.

The idea of using a package for a built-in package manager instead of an executable installer is a common one on many platforms, with iOS and kin being similar. On FreeBSD, which also got a NymphCast port, you’d create a bundle for the pkg package manager, although you can also whip up an installer. In the case of NymphCast there is a ‘universal installer’ built into the Makefile after compilation via the fully automated setup.sh shell script, using the fact that OSes like Linux, FreeBSD and even Haiku are quite similar on a folder level.

That said, the Haiku port of NymphCast is still as much of a Beta as Haiku itself, as detailed in the write-up which I did on the topic. Once Haiku is advanced enough I’ll be creating packages for its pkgman package manager as well.

The Linux Chaos Vortex

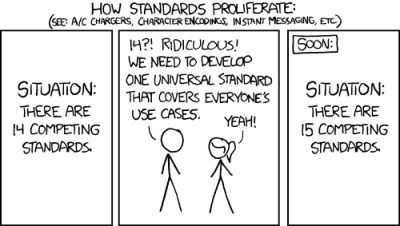

There is a simple, universal way to distribute software across Linux distributions, and it’s called the ‘tar.gz method’, referring to the time-honored method of distributing source as a tarball, for local compilation. If this is not what you want, then there is the universal RPM installation format which died along with the Linux Standard Base. Fortunately many people in the Linux ecosystem have worked tirelessly to create new standards which will definitely, absolutely, totally resolve the annoying issue of having to package your applications into RPMs, DEBs, Snaps, Flatpaks, ZSTs, TBZ2s, DNFs, YUMs, and other easily remembered standards.

There is a simple, universal way to distribute software across Linux distributions, and it’s called the ‘tar.gz method’, referring to the time-honored method of distributing source as a tarball, for local compilation. If this is not what you want, then there is the universal RPM installation format which died along with the Linux Standard Base. Fortunately many people in the Linux ecosystem have worked tirelessly to create new standards which will definitely, absolutely, totally resolve the annoying issue of having to package your applications into RPMs, DEBs, Snaps, Flatpaks, ZSTs, TBZ2s, DNFs, YUMs, and other easily remembered standards.

It is this complete and utter chaos with Linux distros which has made me not even try to create packages for these, and instead offer only the universal .tar.gz installation method. After un-tar-ing the server code, simply run setup.sh and lean back while it compiles the thing. After that, run install_linux.sh and presto, the whole shebang is installed without further ado. I also provided an uninstall_linux.sh script to complete the experience.

That said, at least one Linux distro has picked up NymphCast and its dependencies like Libnymphcast and NymphRPC into their repository: Alpine Linux. Incidentally FreeBSD also has an up to date package of NymphCast in its repository. I’m much obliged to these maintainers for providing this service.

Perhaps the lesson here is that if you want to get your neatly compiled and packaged application on all Linux distributions, you just need to make it popular enough that people want to use it, so that it ends up getting picked up by package repository contributors?

Wrapping Up

With so many details to cover, there’s also the easily forgotten topic that was so prevalent in the Windows installer section: integration with the desktop environment. On Windows, the Start menu is populated via simple shortcut files, while one sort-of standard on Linux (and FreeBSD as corollary) are Freedesktop’s XDC Desktop Entry files. Or .desktop files for short, which purportedly should give you a similar effect.

Only that’s not how anything works with the Linux ecosystem, as every single desktop environment has its own ideas on how these files should be interpreted, where they should be located, or whether to ignore them completely. My own experiences there are that relying on them for more advanced features, such as auto-starting a graphical application on boot (which cannot be done with Systemd, natch) without something throwing an XDG error or not finding a display is basically a fool’s errand. Perhaps that things are better here if you use KDE Plasma as DE, but this was an installer thing that I failed to solve after months of trial and error.

Long story short, OSes like Windows are pretty darn easy to install applications on, MacOS is okay as long as you have bought into the Apple ecosystem and don’t mind hanging out there, while FreeBSD is pretty simple until it touches the Linux chaos via X11 and graphical desktops. Meanwhile I’d strongly advise to only distribute software on Linux as a tarball, for your sanity’s sake.

Your closing paragraph is the TL;DR.

The situation is a tale old as time and so much has been tried to solve the problem as long as I have lived. It seems to be akin to Brooks’ “No Silver Bullet” thesis, but applied to the distribution/platform problem rather than software engineering.

I do not think I will live long enough to see the eventual solution, if indeed one exists.

This is silly.

Windows is a cesspit of malware BECAUSE the standard way to install software is to download random files from random sites on the Internet, then execute them.

Distribution maintained packages are soooooooooo much superior. E.g., when you use apt to install a package from Debian’s repositories, that package has had additional vetting. With Windows, or even Arch’s AUR, you are getting possible malware from untrusted entities– both have been sources of malware.

If you can type “apt-get install thingy” then you can also type “winget install thingy” too.

People download, compile and execute random software (including scripts copy-pasted from obscure forums) from internet also under Linux (or Android if Nigerian Prince calls them personally and politely asks).

What is silly, is fact that for last 25 years we put so much effort to make technology accessible for even most incompetent people and verry little to make people more competent to use technology. A lot of people still:

– think internet is one app (not even a service) – if the app i down than internet is down.

– think that other apps are not internet – if internet is down and their favorite app is not working they think other app will cover it (I met a guy working on a vessel – antenna was down in the middle of ocean and we tried to explain him that internet is down so no fb, wa, email and www and he replied “good I have viber”).

– don’t understand that app is fancy name for software.

– don’t know the difference between file and folder.

– don’t understand that communicators, social media, emails and other services are not happening “on their phone” only.

People like this are mostly on Windows, MacOS or Android. But only Windows gives them freedom of installing whatever they like since day zero. Linux requires gaining some competence before you can do whatever you wish. Here is the real reason why Windows has it’s malware problems while Linux doesn’t

The “masses” are never going to become expert or even “competent” with computer systems, because it’s a tool for achieving other ends and not the point in itself for the vast majority of people out there. Plus, half of them are pretty dumb.

It’s quite ironic that people on Hack-a-Day can’t see it.

100% TRUE. I work with technology and people as well as retail electronics as people and it’s amazing how much computer illiteracy is out there. I have to get onto an uncle constantly not to let people REMOTELY FIX HIS COMPUTER FOR A PAYOUT. Sigh.

Windows is a cesspit of malware because it’s popular enough that if even a very small percent of users get infected, it’s profitable for the malware writers.

That’s also why they can’t maintain all the world’s software in the repository. Nobody’s paying them to check through millions and millions of software titles and just keeping up with the most popular is a massive chore, which is why Debian’s repositories are known to be perpetually out of date and updates take forever to percolate through the system.

If there were any more software available, it would probably not get included and people would have to add other repositories to use the system. You know what happens next if you add the Nigerian Prince’s repository as a trusted source?

Also, how do you get your new software included in the repository if it’s not already popular enough, while the users can’t access the software since it’s not in the repository?

Catch-22.

You need to have a direct-to-user distribution channel OR you need to know one of the developers in charge and buy them beer, OR you need to become a distro developer yourself to put your own software in the repository. Only one of these options really works when scaled up to millions of software titles, unless you do like Google and just shovel everything in the repository, malware and all, without really checking.

RPM, DNF and YUM refer to the same thing, though; between them and Debian .apt format, they represent the traditional way of building systems by collecting a coherent set of libraries and applications. Unfortunately, modern rapid software development practices often clash with it, by demanding specific and divergent dependencies for each separate application.

This spurned an alternative OS packaging design, with a small immutable OS core (e.g. Fedora silverblue aka atomic) and applications bundled with their library dependencies, in flatpak, snap and appimage formats.

I like the old way better because it is auditable and straightforward to keep track, in case of problems or vulnerabilities.

The new way works but leads to a Zoo of versions, known from Windows as a DLL hell.

Windows kind of chooses the worst of both worlds: arbitrary DLL bundling, AND the base OS is very NOT immutable.

RPM was never standard for Linux distributions. The commercial company, Redhat, created a fake standard to promote their (inferior[1]) product to ignorant folk (e.g., management types) who didn’t know better. At the time, Debian’s deb and Slackware’s tgz were the most common packaging formats.

[1] inferior, as while Debian’s package manager was fully functional before Redhat even existed, Redhat came up with a new package manager that couldn’t even delete automatically installed package dependencies. “up2date” was pathetic, but was all Redhat had until they adopted yum from Yellow Dog Linux (around a decade after Yellow Dog introduced it).

The only thing .rpm had over already established formats like .deb is it is easier to get up to speed on creating packages.

Why don’t people just release good old appimages? They’re such an easy way to share applications

Instead we get snap (hellishly slow), flatpak (much faster), docker (what even is this?)

QNX’s developer system at one point had a packaging system where every installed package was bind-mounted on top of the root FS as read-only, uninstalling a package was as simple as un-mounting & deleting the package file. The downside was that at boot it had to index and mount all the packages and the mount table and process list (yay microkernel!) could be enormous. I want the sandbox of docker, the simplicity of QNX’s package system, and the permissions system of a modern cellphone OS (both Android and iOS have some [reasonable for most people] permissions abilities). There are now 37 standards. (You’re welcome)

I’m a huge fan of the iOS permissions system and wish it was part of *nix/windows. I.e. “Do you want this application to access your files? Access the internet? Use your camera? Etc…”. Sandbox everything as if it was running in a VM. Lock down OS files and memory unless explicitly granted. I would worry a lot less about untrusted binaries if there were some basic safeguards in place.

Yeah, I was surprised AppImage wasn’t mentioned. If a distribution-specific package isn’t available, AppImage is the next best thing.

The strengths of appimages also end up being some of their biggest weaknesses once you start trying to shoehorn software with complex dependencies into them.

AppImages are supposed to be completely self-contained, which sounds great on paper, but in practice most people discover that they don’t actually want every single interdependent part of.. say, KDE/qt bundled with every single KDE/qt app, at whatever minor differing revision the AppImage was compiled with.

They are huge and they are not always easy to make. But i agree that they are probably the best we have now, because once somebody takes the time to make one, they just work.

I use appImages of FreeCad and InkScape for the latest versions of their software. It does work well, at least on KUbuntu LTS. Don’t mind this format at all. Disk Space is ‘cheap’ and plentiful.

If you’re making a product, then it’s probably best to have it run in a browser. Browser is the common platform.

I would argue that for Windows, the deployment is not at all easier, it is just expected. Your code will go nowhere unless you provide an installer, so you must fight your way through InstallShield. Linux is “I made this useful thing, use it or don’t, whatever. This is as far as I go, it’s my weekend time.”

Much Windows software can simply be run from any folder as is. For example, the last time I played Kerbal Space Program, I simply downloaded the file and unzipped it into a folder on the desktop, then launched the executable inside.

Most of the installers too do just three things: copy the files to the program folder, add a start menu shortcut, and register the uninstaller. That’s it.

“then there is the universal RPM installation format which died”

Which was already a sort of clone (not literally) of dpkg. A new standard. I blame RPM for starting the package manager war.

My first GNU/Linux was RedHat, well before there was an Enterprise version. I used to manage a ton of SLES machines for work and as a result, I cannot stand RPM and the yellowdog updater (YUM). It’s horrible. Who decided that update and upgrade were the same things? I’m doing apt update on Debian and it updates the local information with the internet but everything stays as it is. I do yum update and it does both update the local information, and upgrades my entire system without warning. Doesn’t even ask if I want to do that, no confirmation, nothing, it just does it. When you run a combination of SLES and Debian servers, across hundreds of servers, that can be a huge pain in the rear. (this was 20 years ago, these days, most servers use management tools or are containerized, I’m an old-school linux admin, beard and everything).

It is perfectly fine to just describe compilation steps for Linux and leave it at that. That you for your contribution to software commons, you are awesome!

Wrong parent, should have been top.

With the rise of various immutable linux distros (bluefin, bazzite, etc) flatpak seems to be becoming a mostly-universal target for desktop linux. So that’s cool.

The real question is do the laptop stickers on the artwork exist? and where can I get them!

I would avoid those: they’re all upside-down!

The centre (bird) one does at least: it’s the Ada mascot. Hackaday stickers also exist, but you’re most likely to get them at one of the Hackaday real-life events if you want the legit ones :)

And people wonder why some developers prefer to write their apps as web pages.

There used a be a great open-source cross-platform installer, but I can’t remember the name of it. It was TCL/TK based IIRC (probably why it’s not known today). It was so easy to use, from both the developer and user point of view. It was such a relief to move away from InstallShield to something open source, single source, and user friendly.

Anybody remember it?

Just a little tip, anyone developing primarily for Windows should test their programs under WINE too. That way they can easily ensure a Linux compatible versions just by telling us Linux users “this software has been tested to work under Wine version…” and not have to wander in to the chaos vortex of all the usual Linux installer options. I believe this is method is (or historically was) deliberately used by software packages including the LTSpice circuit simulator.