The electric vehicle revolution has created market forces to drive all sorts of innovations. Battery technology has progressed at a rapid pace, and engineers have developed ways to charge vehicles at ever more breakneck rates. Similarly, electric motors have become more powerful and more compact, delivering greater performance than ever before.

In the latter case, while modern EV motors are very capable things, they’re also reliant on materials that are increasingly hard to come by. Most specifically, it’s the rare earth materials that make their magnets so good. The vast majority of these minerals come from China, with trade woes and geopolitics making it difficult to get them at any sort of reasonable price. Thus has sprung up a new market force, pushing engineers to search for new ways to make their motors compact, efficient, and powerful.

Rare

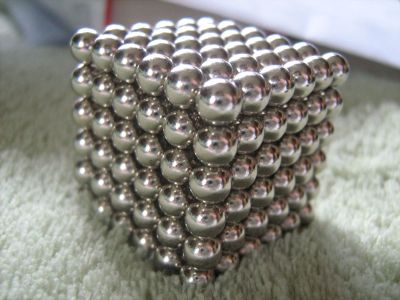

Rare earth materials have become a hot button issue in recent decades, and they’ve also become a familiar part of our lives. If you remember playing with some curiously powerful magnets at some point, you’ve come across neodymium—a rare earth material of wide application. The element is alloyed with iron and boron to produce some of the strongest magnets readily available on the commercial market. You’ll find them in everything from hard drives to EV motors, and stuck to a great many fridges, where they’re quite hard to peel off. At times, neodymium is also alloyed with other rare earths, like terbium and dysprosium, which can help create powerful magnets that are able to resist higher temperatures without failure.

We come across these magnets all the time, so they might not feel particularly rare. Indeed, the rare earth elements—of which there are 17 in total—are actually fairly abundant in the Earth’s crust. The problem is that they are thinly spread, often only found as trace elements rather than in rich ore deposits that are economical to mine. Producing any useful amount of rare earth materials tends to require processing a great deal of raw material at significant cost. As it stands, China has gained somewhat of a monopoly on rare earths, controlling up to 92% of global processing capability and 60 to 70% of mining capacity. In happier times, this wouldn’t be such a problem. Sadly, with the extended battles being fought over global trade at the moment, it’s making access to rare earths both difficult and expensive.

This has become a particular problem for automotive manufacturers. It’s no good to design a wonderful motor that needs lots of fancy rare earth magnets, only to find out a year later that they’re no longer available and that production must shut down. Thus, there is a serious desire on the part of major automakers to produce high-performance motors that don’t require such fancy, hard-to-come-by materials. Even if they come with a small cost penalty in materials or manufacturing, they could save huge sums of money if they avoid a production shutdown at some point in the future. Large manufacturing operations are slow, lumbering things that need to run on long timescales to operate economically, and they can easily be derailed by supply disruptions. Securing a solid motor supply is thus key to companies looking to build EVs en masse in the immediate future.

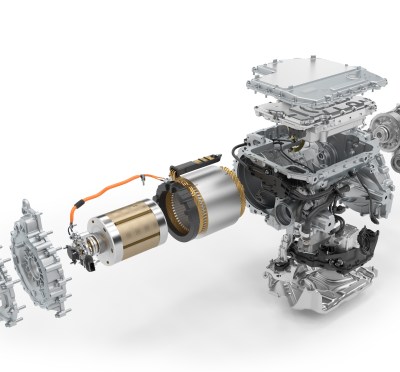

BMW has, to a degree, solved the problem by making different kinds of motors. Rather than trying to find other ways to make powerful magnets, the German automaker put engineering efforts into developing highly-efficient motors that generate their own magnetic fields via electricity. Instead of using permanent magnets on the rotor, they use coils, which are electrically excited to generate a comparable magnetic field. Thus, rare earth magnets are replaced with coil windings, which are much easier to source. These motors are referred to as Electrically Excited Synchronous Motors (EESM), and are distinct from traditional induction motors as they are creating a magnetic field in the rotor via supplied electric current rather than via induction.

This method of construction does come with some trade offs, of course, such as heat generated by the rotor coils, and the need for slip rings or brushes to transfer power to the coils on the rotor. However, they manage to neatly sidestep the need for rare earth materials entirely. They are also more controllable. Since it’s possible to vary the magnetic field in the rotor as needed, this can be used to make efficiency gains in low-load situations. They’re also less susceptible to damage from overtemperature that could completely destroy the magnets in a permanent magnet motor.

BMW was inspired to take this route because of a spike in neodymium prices well over a decade ago. Today, that decision is bearing fruit—with the company less fearful of supply chain issues and production line stoppages due to some pesky magnets. You’ll find EESM motors in a range of BMW products, from the iX1 to the i7, and even the compact CE 02 scooter. The company’s next generation of electric models will largely use EESM motors for rear-wheel-drive models, while using asynchronous motors up front to add all-wheel-drive to select models. The German automaker is not the only player in this space, either. A range of third-party motor manufacturers have gotten on board the EESM train, as well as other automakers like Nissan and Renault.

Nissan has similarly gotten onboard with EESM technology. Note the contact surfaces for the brushes used to deliver electricity to the coils in the motor.

Don’t expect every automaker to rush into this technology overnight. Retooling production lines to make different types of motors takes time, to say nothing of the supporting engineering required to control the motors and integrate them into vehicle designs. Many automakers will persevere with permanent magnet motors, doing what they can to secure rare earth supplies and shore up their supply chains. However, if the rare earth crisis drags on much longer, expect to see ever more reliance on new motor designs that don’t need rare earth magnets at all.

Everything old is new again. DC motors with electromagnets have been on the market since the 1870’s or so.

I had similar thoughts when I read “creating a magnetic field in the rotor via supplied electric current rather than via induction”: “Oh, so we’re back to using brushes I guess.”

There’s also rotary transformers, more typically used in stationary motors.

The main limitation is size and weight because you need to transmit high currents at a fairly low frequency, so the rotary transformer might be close to the size of the motor itself.

You could reduce the size of the transformer by using a higher frequency, but that’d require embedding active electronics in the rotating part to bring it back down to what you actually need.

could you have the exciter coil stationary powered through a hollow axle, and use a rotor that shapes the exciter field, similar in appearance to a two wire externally excited automotive alternator.

that way there would be no need for brushes.

I suppose you could, similar to a hybrid stepper motor. The two challenges would be cooling, and the fact that you’d have to have a hollow axle and rotor. Minimizing the air gaps without crashing the parts into one another as the temperature and load changes might be an interesting design challenge.

Yeah I was pretty sure this was already standard for large motors. The rare-earth shortage scare has always been tech industry hype. Just ignore it.

100% agree, any textbook on electrical engineering introduces this concept early on.

Rare magnets make designs cheaper (no messing with extra coils) and easier to mass-produce, to they are around mostly for that exact reason, saving a buck here and there.

Regardless, reexamining the basics never hurts – and I hope BMW really hired educated engineers, and not high (or middle) school dropouts in overseas.

More powerful magnets also make the motors more efficient with better torque characteristics and greater power density. Try making a drone motor with some ferrite or alnico magnets.

That.

I had suspicion it has to do with torque, too, just didn’t know the topic good/well enough.

You get 5-10x the torque out of neodymium magnets of the same size, which is why we didn’t have toy drones in the 1980’s.

Yeah, nothing new there…

They just decided to reuse old tech properely designed with new tools and for new applications… that feels like some add for BMW more than anything interesting for us…

And everybody were happy to switch to brushless motors!

The actual problem is that rare earth elements are products of nuclear decay chains, so they occur in minerals where there used to be radioactive elements like Thorium, Uranium, and Radium. Since these elements last for eons, much of it still remains. For example, in Monzanite.

https://www.smenet.org/What-We-Do/Technical-Briefings/Thorium-as-a-Byproduct-of-Rare-Earth-Element-Produ

Now, the issue isn’t that these minerals are very rare or difficult to find. The issue is that mining for the REE materials leaves behind literal mountains of low level nuclear waste which should be adequately handled and disposed of. In many places it’s practically outlawed due to regulations that are impossible to meet. This drives up the cost of production where safe waste processing is mandatory and strictly controlled and monitored by environmentalists and public authorities. That is, everywhere else except in China and various other places where you can just dump the stuff around while nobody’s looking. Example:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1982_Bukit_Merah_radioactive_pollution

So you can guess why China now commands a near monopoly on the stuff. It’s not that they’re the only country that can produce it – it’s that they’re the cheapest country to produce it, to the point of bankrupting every other company in every other country that wanted to do it. Everybody else sold off their operations as unprofitable, and once the competition was gone, the prices went up and the supply became restricted. There’s nobody else left because nobody wants to put their necks in that loose noose with the other end of the rope held by the CCP.

Just put the waste back in the mine where you got it from, problem solved.

“Put that thing back where it came from, or so help me!”

Wow, a Monsters, Inc. quote on Hackaday. Nice!

+1 for both of you!

It’s curious how you can never dig a hole large enough to put the dirt back in. It’ll always leave a mound.

But seriously, you could do that after you’ve stopped mining, but that’s after the mine stops making profit. You would have to put money aside for the decommissioning – otherwise it’s nobody’s job. Now guess how the Chinese can do it so cheaply?

Putting the dirt back in the hole it came from doesn’t exactly solve the problem though, if it’s an open pit mine. It’ll continue to fill up with water, and the rock that you broke and ground up into mud to separate the minerals keeps leeching the remaining heavy metals and radioisotopes into the environment.

Clay caps are one of the oldest civil engineering methods.

Not perfect.

Would be interesting to see if baking such a nuclear waste pie out of clay is good enough for anti-nuclear activists, because that waste is going to be there for billions of years to come, and there’s literal mountains of it.

Or whether it’s double standards all the way down.

Hmmm, yes I could see mining and processing near each other in some, out of the way, extremely cold, hotly contested island. Poor island.

Greenland has the minerals, but it lacks all infrastructure and energy to process and transport it, and it’s inaccessible half the year. You basically have to haul everything in and out by helicopter.

It’s a very expensive proposition that doesn’t make any sense, considering that the main problem for the US is not about getting the minerals – there are many abandoned REE mines on US soil – it’s the processing capacity that is underdeveloped and missing. The processing plants are decades old, run down and inefficient, closed or re-purposed for something else entirely, and the expertise to design and run them was lost after everything was off-shored 20 years ago.

Withdrawing from Afghanistan also made no sense yet the man still did it.

100% spot on correct!

Q: Is a major problem with rare earths mining and processing in the US the presence of thorium in the ore and Chinese dumping against any startups elsewhere?

Grok: Yes, both the presence of thorium in rare earth ores and China’s market practices, including allegations of dumping, represent major challenges for rare earth mining and processing in the US, as well as for startups globally attempting to enter the sector. These issues contribute to the US’s heavy reliance on imports, with China controlling approximately 70% of global rare earth mining, over 90% of refining, and nearly all magnet production. Below, I’ll break this down based on available evidence.

[huge snip]

This US Senate bill described in the following video I watched six years ago was the answer not just for the US, but the entire Western world; a cooperative effort. Went nowhere. The bill died.

That’s one of the advantages Chinese capitalism can have where the government directs corporations instead of the other way around as it is in the US. It can result in large, coordinated, targeted, successful efforts.

Senate Bill 2093 Rare Earth Cooperative 21st Century Manufacturing Act introduced by Senator Marco Rubio

Aug 29, 2019

S. 2093 is a bill to establish a Thorium-Bearing Rare Earth Refinery Cooperative.

Introduced by Senator Marco Rubio, this Senate Staffer briefing shows the legislation being argued in favor by U.S. Army Brigadier General John Adams (Retired), the senior geoscientist Dr. Ned Mamula (USGS, DoE, CIA), James Kennedy (expert on Rare Earths), and Mark Noga who’s spent 25 years sourcing Rare Earths for automotive, medical, aerospace and defense systems.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8mO6hZFGnA

That was inended to be a reply to Dude.

I can’t disagree with a lot of what you are saying except to note that the products of nuclear decay chains are all radioactive except for the final element, lead. The only rare earths created by nuclear processes would be the result of nuclear fission which does create elements lighter than lead.

This is not a good source of mine-able rare earth elements :-)

The rare earths we mine today were created in the supernovas that were the precursors to our solar system.

Cheers.

Which does tend to happen When you have four billion years of time, deposits of uranium and thorium undergo spontaneous fission.

For the longest period of time, the most powerful electric motors available have been synchronous 3-phase motors (forget DC series-wound motors; they require high-maintenance brushes and commutators…but they areVERY high-torque).

While I like this approach better, I still find it frustrating that advances like artificial tetratenite (US 11,462,358 B2) are apparently just being sat on and not utilized, and that the United States’ mineral resources are also apparently just being sat on and not utilized. How expensive do trade wars have to get before you stop using China to circumvent your own country’s environmental and labor regulations (or lobby against certain regulations, or dust off inventions that make it a moot point)?

Unfortunately, the sole reason why we have things like cheap solar panels or cheap high grade neodymium magnets is that environmental and labor regulations are being circumvented. If things were done properly and responsibly, the price would go up and the demand would crash down, and most of the whole business would go bye bye.

It’s kinda like building your society on the assumption that you’re always going to have cheap oil, and then 1973 rolls along…

Alternators in other words….

Yes indeed, I came here to say just that (too)!

Or to expand a bit: a motor and a generator are of course the same thing, just reversed. An alternator (generator) can be a nice brushless DC motor if you feed the inner coil with a suitable current, delivered with the built in slip rings.

In an alternator that current is usually rectified from the output, regulated by the voltage regulator (so different RPM’s and loads all produce 12v), but you can just remove all rectifier and regulator circuits and feed in your own current.

Alternators are incredibly tough devices. In the northern countries, they operate between -40c – +37C, in wet salty environments in the winter, dusty and dry in the summers, yet soldiers on easily over 200 000km. Anything based on alternators will be robust and reliable.

Car parts face rough conditions, but they don’t actually have to be very durable. A typical engine runs for less than 5000 hours in total. The average alternator will see less than 6 months of continuous use.

That’s also why it doesn’t really matter whether you use brushes or other mechanical compromises. It doesn’t need to last forever.

Tesla’s first cars all used cheapish synchronous motors (Models S and X), and used expensive and complicated controllers to drive them. China copied this approach, but was limited by their ability to design and manufacture the electronics needed. Then Tesla came out with the Model 3, whichever used permanent magnet motors, and simpler, cheaper controllers. China swiveled too, realizing that they held all the cards. Now they dominate the market, due to this HUGE strategic mistake by Tesla.

Synchronous motors with electromagnets for the rotor are nothing new. Their downsides are they require copper and also consume electricity for a static magnetic field. They can get their power via slip rings or via induction.

Rare-earth-free permanent magnets are new developments. They have downsides like production challenges and may not perform as well as rare-earth magnets.

Brush up on your brushes! Clean non sticky brush holders, dust free insides for low wear.

Why not use induction motor with low resistance rotor and advanced VFD? Those probably have even less rotor losses than slip ring or ring transformer excited synchronour motor, and are the most tough and bulletproof source of torque known to man.

We like regenerative braking too much for that.

VFD weight may be a little much. Incredibly tunable, reliable (I have yaskawas and omrons that turned thirty two this past year still chugging 20/7) but the weight and packaging might be a problem. A bare 480VAC 100 HP drive with heatsink and cooling will push 200 pounds easy, forget weatherproofing it to Nema 4X. At 550 to 1kV, you might be getting more reasonable though. And then you have all the neat tricks of a vfd like flying starts, flux vectoring, shaft position, etc. Plenty of multi motor drives already exist, and that weight includes a lot of the safety and monitoring electronics you already need for EVs, and can replace components like diffs and CVs. I’m imagining speeding up the outside wheels on turns, snapping in torque at the apex precisely, and you get the carrier frequency sound for the buffs who like engine note. “I prefer a 35kHz, so it sounds like banshee shriek when I lay into the motor” I can imagine them saying