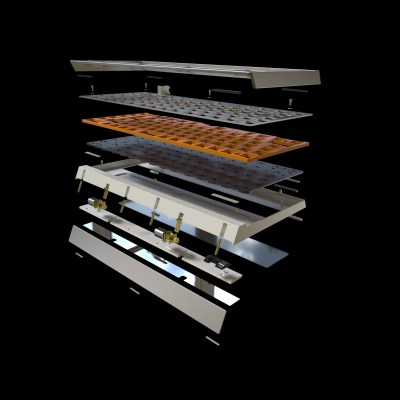

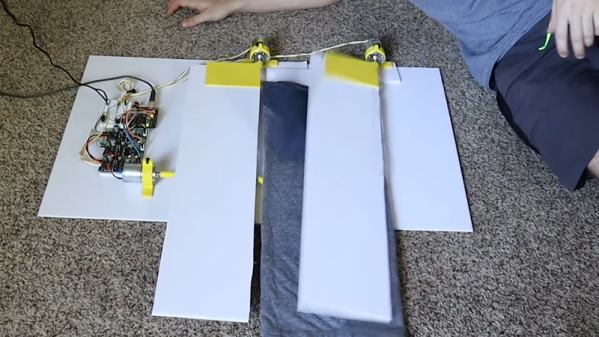

The electric vehicle revolution has created market forces to drive all sorts of innovations. Battery technology has progressed at a rapid pace, and engineers have developed ways to charge vehicles at ever more breakneck rates. Similarly, electric motors have become more powerful and more compact, delivering greater performance than ever before.

In the latter case, while modern EV motors are very capable things, they’re also reliant on materials that are increasingly hard to come by. Most specifically, it’s the rare earth materials that make their magnets so good. The vast majority of these minerals come from China, with trade woes and geopolitics making it difficult to get them at any sort of reasonable price. Thus has sprung up a new market force, pushing engineers to search for new ways to make their motors compact, efficient, and powerful.

Continue reading “Finding A Way To Produce Powerful Motors Without Rare Earths”