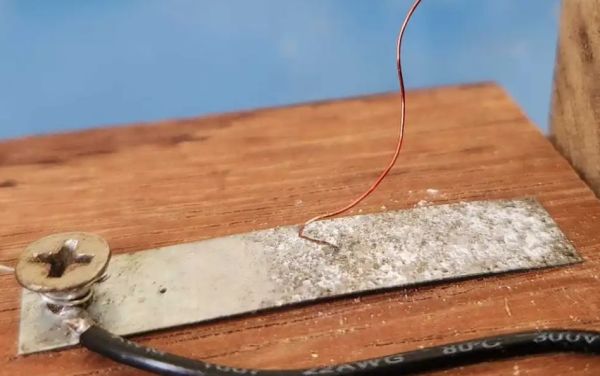

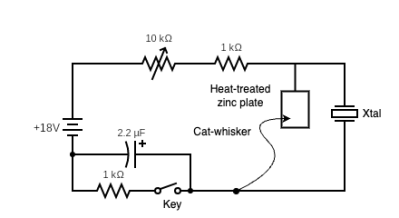

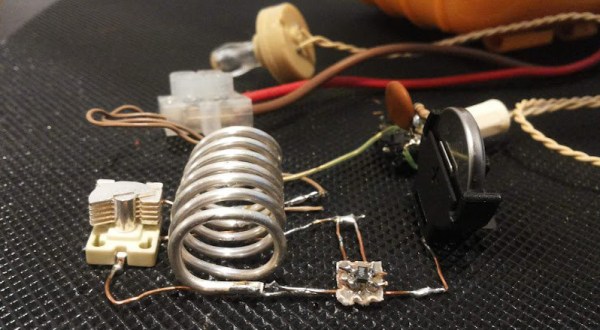

A staple of starting off in electronics ion years past was the crystal set radio, an extremely simple AM radio receiver with little more than a tuned circuit and a point contact diode as its components. Point contact diodes have become difficult to find but can be replaced with a cats whisker type detector, but what about listening to the resulting audio? These circuits require a very high impedance headphone, which was often supplied by a piezoelectric crystal earpiece. [Tsbrownie] takes a moment to build a replacement for this increasingly hard to find part.

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise, but we were still slightly taken aback to discover that inside these earpieces lies the ubiquitous piezoelectric buzzer element. Thus given a 3D-printed shell to replace the one on the original, it’s a relatively simple task to twist up a set of wires and solder them on. The result is given a test, and found to perform just as well as the real thing, in fact a little louder.

In one sense this is such a simple job, but in another it opens up something non-obvious for anyone who needs a high impedance earpiece. The days of the crystal radios and rudimentary transistor hearing aids these parts were once the main target for may both have passed, but just in case there’s any need for one elsewhere, now we can fill it. Take a look at the video, below the break.

Fancy trying a crystal radio? We’ve got you covered.