As frustrating as having an atmosphere can be for physicists, it’s just as bad for astronomers, who have to deal with clouds, atmospheric absorption of certain wavelengths, and other irritations. One of the less obvious effects is the distortion caused by air at different temperatures turbulently mixing. To correct for this, some larger observatories use a laser to create an artificial star in the upper atmosphere, observe how this appears distorted, then use shape-changing mirrors to correct the aberration. The physical heart of such a system is a deformable mirror, the component which [Huygens Optics] made in his latest video.

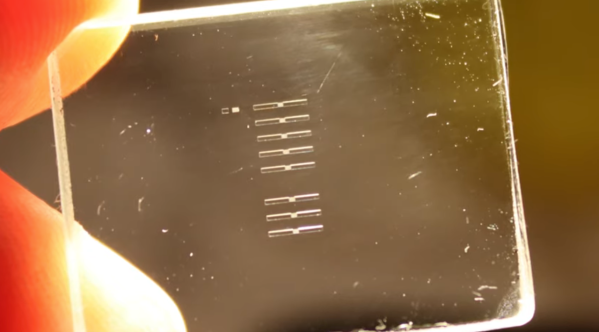

The deformable mirror is made out of a rigid backplate with an array of linear actuators between it and the thin sheet of quartz glass, which forms the mirror’s face. Glass might seem too rigid to flex under the tenth of a Newton that the actuators could apply, but everything is flexible when you can measure precisely enough. Under an interferometer, the glass visibly flexed when squeezed by hand, and the actuators created enough deformation for optical purposes. The actuators are made out of copper wire coils beneath magnets glued to the glass face, so that by varying the polarity and strength of current through the coils, they can push and pull the mirror with adjustable force. Flexible silicone pillars run through the centers of the coils and hold each magnet to the backplate.

A square wave driven across one of the actuators made the mirror act like a speaker and produce an audible tone, so they were clearly capable of deforming the mirror, but a Fizeau interferometer gave more quantitative measurements. The first iteration clearly worked, and could alter the concavity, tilt, and coma of an incoming light wavefront, but adjacent actuators would cancel each other out if they acted in opposite directions. To give him more control, [Huygens Optics] replaced the glass frontplate with a thinner sheet of glass-ceramic, such as he’s used before, which let actuators oppose their neighbors and shape the mirror in more complex ways. For example, the center of the mirror could have a convex shape, while the rest was concave.

This isn’t [Huygens Optics]’s first time building a deformable mirror, but this is a significant step forward in precision. If you don’t need such high precision, you can also use controlled thermal expansion to shape a mirror. If, on the other hand, you take it to the higher-performance extreme, you can take very high-resolution pictures of the sun.