Apple hasn’t always had refined user experiences in their operating systems. In the distant past of the ’90s they were still kind of clunky computers that were far from the polished, high-end consumer machines of the modern era. That wasn’t all that Apple offered back then, though. They had a long-forgotten alternative operating system that was called A/UX designed for government applications, and [Keriad] is here to show us this relic operating system and port DOOM to it.

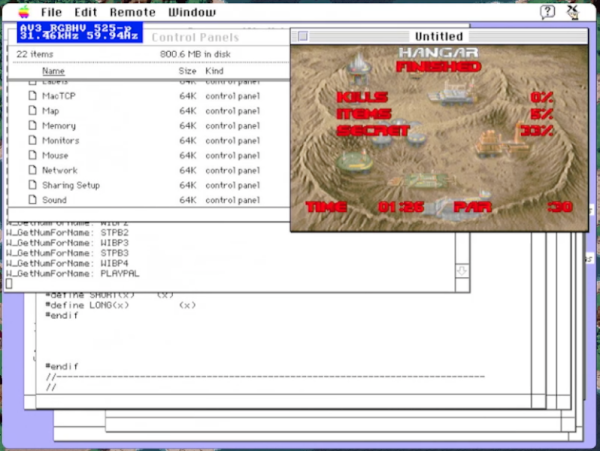

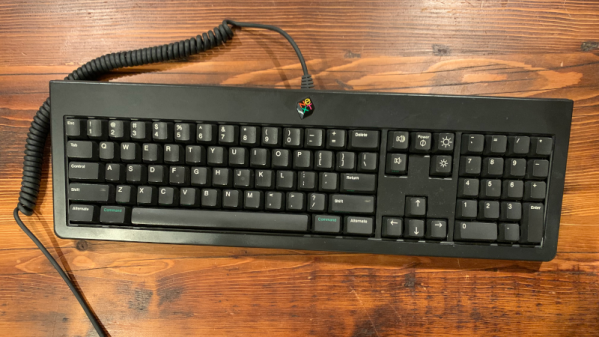

A/UX was designed in the pre-PowerPC days when Macintosh computers ran on Motorola 68000 chips. Luckily, [Keriad] has a Mac Quadra 800 with just such a chip that is still fully-functional. DOOM was developed with the NeXTSTEP operating system which can run on old Macs thanks to another tool called MacX which allows X11 applications to run on Mac. A version of gcc for A/UX was found as well and with the source code in hand they were eventually able to compile a binary. There were several hiccups along the way (including the lack of sound) but eventually DOOM was running on this forgotten operating system.

The main problem with the build in the end, besides the lack of sound, is that the game only runs at 2 – 3 frames per second. [Keriad] speculates that this is due to all of the compatibility layers needed to compile and run the game at all, but it’s still impressive. As far as we know, [Keriad] is the first person to port DOOM to this OS, although if you’re looking for something more straightforward we would recommend this purpose-built Linux distribution whose sole task is to get you slaying demons as quickly as possible.