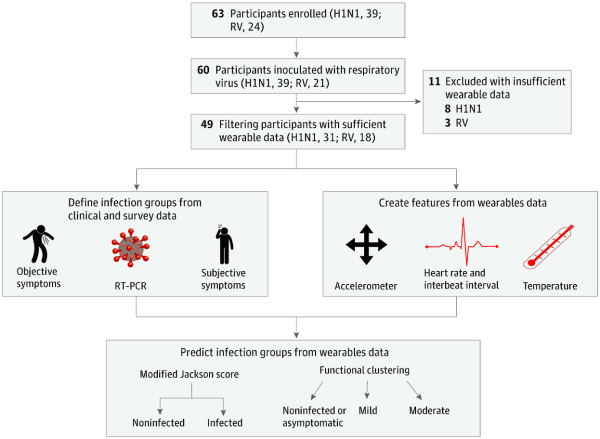

Surprisingly there are no pre-symptomatic screening methods for the common cold or the flu, allowing these viruses to spread unbeknownst to the infected. However, if we could detect when infected people will get sick even before they were showing symptoms, we could do a lot more to contain the flu or common cold and possibly save lives. Well, that’s what this group of researchers in this highly collaborative study set out to accomplish using data from wearable devices.

Participants of the study were given an E4 wristband, a research-grade wearable that measures heart rate, skin temperature, electrodermal activity, and movement. They then wore the E4 before and after inoculation of either influenza or rhinovirus. The researchers used 25 binary, random forest classification models to predict whether or not participants were infected based on the physiological data reported by the E4 sensor. Their results are pretty lengthy, so I’ll only highlight a few major discussion points. In one particular analysis, they found that at 36 hours after inoculation their model had an accuracy of 89% with a 100% sensitivity and a 67% specificity. Those aren’t exactly world-shaking numbers, but something the researchers thought was pretty promising nonetheless.

One major consideration for the accuracy of their model is the quality of the data reported by the wearable. Namely, if the data reported by the wearable isn’t reliable itself, no model derived from such data can be trustworthy either. We’ve discussed those points here at Hackaday before. Another major consideration is the lack of a control group. You definitely need to know if the model is simply tagging everyone as “infected” (which specificity does give us an idea of, to be fair) and a control group of participants who have not been inoculated with either virus would be one possible way to answer that question. Fortunately, the researchers admit this limitation of their work and we hope they will remedy this in future studies.

Studies like this are becoming increasingly common and the ongoing pandemic has motivated these physiological monitoring studies even further. It seems like wearables are here to stay as the academic research involving these devices seems to intensify each day. We’d love to see what kind of data could be obtained by a community-developed device, as we’ve seen some pretty impressive DIY biosensor projects over the years.