Once upon a time, transmutation of the elements was a really big deal. Alchemists drove their patrons near to bankruptcy chasing the philosopher’s stone to no avail, but at least we got chemistry out of it. Nowadays, anyone with a neutron source can do some spicy transmutation. Or, if you happen to have a twelve meter sphere of liquid scintillator two kilometers underground, you can just wait a few years and let neutrinos do it for you. That’s what apparently happened at SNO+, the experiment formally known as Sudbury Neutrino Observatory, as announced recently.

The scinillator already lights up when struck by neutrinos, much as the heavy water in the original SNO experiment did. It will also light up, with a different energy peak, if a nitrogen-13 atom happens to decay. Except there’s no nitrogen-13 in that tank — it has a half life of about 10 minutes. So whenever a the characteristic scintillation of a neutrino event is followed shortly by a N-13 decay flash, the logical conclusion is that some of the carbon-13 in the liquid scintillator has been transmuted to that particular isotope of nitrogen.

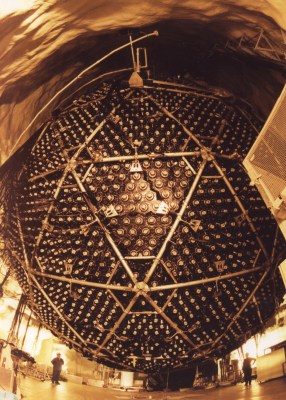

That’s not unexpected; it’s an interaction that’s accounted for in the models. We’ve just never seen it before, because, well. Neutrinos. They’re called “ghost particles” for a reason. Their interaction cross-section is absurdly low, so they are able to pass through matter completely unimpeded most of the time. That’s why the SNO was built 2 KM underground in Sudbury’s Creighton Mine: the neutrinos could reach it, but very few cosmic rays and no surface-level radiation can. “Most of the time” is key here, though: with enough liquid scintillator — SNO+ has 780 tonnes of the stuff — eventually you’re bound to have some collisions.

Capturing this interaction was made even more difficult considering that it requires C-13, not the regular C-12 that the vast majority of the carbon in the scintillator fluid is made of. The abundance of carbon-13 is about 1%, which should hold for the stuff in SNO+ as well since no effort was made to enrich the detector. It’s no wonder that this discovery has taken a few years since SNO+ started in 2022 to gain statistical significance.

The full paper is on ArXiv, if you care to take a gander. We’ve reported on SNO+ before, like when they used pure water to detect reactor neutrinos while they were waiting for the scintillator to be ready. As impressive as it may be, it’s worth noting that SNO is no longer the largest neutrino detector of its kind.